Susan B. Anthony was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to social equality, she collected anti-slavery petitions at the age of 17. In 1856, she became the New York state agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first convention to be called for the sole purpose of discussing women's rights, and was the primary author of its Declaration of Sentiments. Her demand for women's right to vote generated a controversy at the convention but quickly became a central tenet of the women's movement. She was also active in other social reform activities, especially abolitionism.

Lucy Stone was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. She spoke out for women's rights and against slavery. Stone was known for using her birth name after marriage, contrary to the custom of women taking their husband's surname.

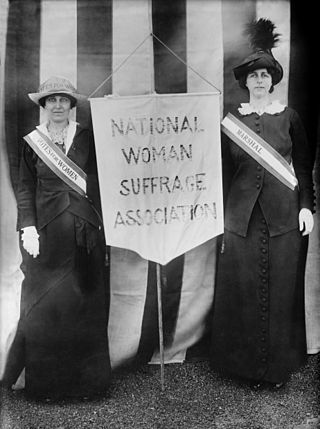

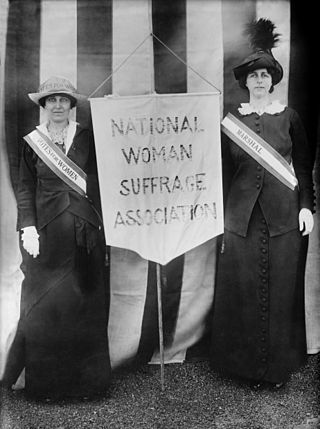

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement split over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution, which would in effect extend voting rights to black men. One wing of the movement supported the amendment while the other, the wing that formed the NWSA, opposed it, insisting that voting rights be extended to all women and all African Americans at the same time.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

The Revolution was a newspaper established by women's rights activists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in New York City. It was published weekly between January 8, 1868, and February 17, 1872. With a combative style that matched its name, it primarily focused on women's rights, especially prohibiting discrimination against women's suffrage in the United States, and women's suffrage in general. It also covered other topics, such as politics, the labor movement, and finance. Anthony managed the business aspects of the paper, while Stanton was co-editor along with Parker Pillsbury, an abolitionist and a supporter of women's rights.

Women's legal right to vote was established in the United States over the course of more than half a century, first in various states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920 with the passing of the 19th Amendment.

The Women's Loyal National League, also known as the Woman's National Loyal League and other variations of that name, was formed on May 14, 1863, to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. It was organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, its president, and Susan B. Anthony, its secretary. In the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time, the League collected nearly 400,000 signatures on petitions to abolish slavery and presented them to Congress. Its petition drive significantly assisted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the U.S. The League disbanded in August 1864 after it became clear that the amendment would be approved.

The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was a single-issue national organization formed in 1869 to work for women's suffrage in the United States. The AWSA lobbied state governments to enact laws granting or expanding women's right to vote in the United States. Lucy Stone, its most prominent leader, began publishing a newspaper in 1870 called the Woman's Journal. It was designed as the voice of the AWSA, and it eventually became a voice of the women's movement as a whole.

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention combined both female and male leadership and attracted a wide base of support including temperance advocates and abolitionists. Speeches were given on the subjects of equal wages, expanded education and career opportunities, women's property rights, marriage reform, and temperance. Chief among the concerns discussed at the convention was the passage of laws that would give women the right to vote.

Stephen Symonds Foster was a radical American abolitionist known for his dramatic and aggressive style of public speaking, and for his stance against those in the church who failed to fight slavery. His marriage to Abby Kelley brought his energetic activism to bear on women's rights. He spoke out for temperance, and agitated against any government, including his own, that would condone slavery.

Hannah Maria Conant Tracy Cutler was an American abolitionist as well as a leader of the temperance and women's suffrage movements in the United States. Cutler served as president of the Ohio Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Cutler helped to shape the merger of two feminist factions into the combined National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex." Some of the more prominent reform activists of that time were members, including women and men, blacks and whites.

The U.S. state of Kansas held a referendum on a proposed constitutional amendment to grant women the full right to vote on November 5, 1867. It was the first-ever referendum on women's suffrage in U.S. history, and specifically sought to amend Section 1, Article 5 of the state constitution to "eliminate the word "male" from the clause defining the qualifications of an elector." The amendment had been approved by the legislature, but had to be ratified by the all-white-male electorate of the state; the proposed amendment shared the November ballot with a proposition to "eliminate the word "white" from the clause defining the qualifications of an elector" and allow African-American males the right to vote. The results of the Kansas election saw both ballot items defeated.

The Hovey Fund was created by a bequest from Charles Fox Hovey (1807-1859), a Boston merchant who supported a variety of social reform movements. Hovey left $50,000 to support abolitionism and other types of social reform, including "women's rights, non-resistance, free trade and temperance." Hovey appointed a committee of trustees to administer the fund, headed by abolitionist Wendell Phillips. Hovey specified that the funds should be spent at the rate of $8,000 per year to meet immediate needs.

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

History of Woman Suffrage is a book that was produced by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Ida Husted Harper. Published in six volumes from 1881 to 1922, it is a history of the women's suffrage movement, primarily in the United States. Its more than 5700 pages are the major source for primary documentation about the women's suffrage movement from its beginnings through the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which enfranchised women in the U.S. in 1920. Written from the viewpoint of the wing of the movement led by Stanton and Anthony, its coverage of rival groups and individuals is limited.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

United States v. Susan B. Anthony was the criminal trial of Susan B. Anthony in a U.S. federal court in 1873. The defendant was a leader of the women's suffrage movement who was arrested for voting in Rochester, New York in the 1872 elections in violation of state laws that allowed only men to vote. Anthony argued that she had the right to vote because of the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, part of which reads, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States."