The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby go into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

Anti-suffragism was a political movement composed of both men and women that began in the late 19th century in order to campaign against women's suffrage in countries such as Australia, Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States. To some extent, Anti-suffragism was a Classical Conservative movement that sought to keep the status quo for women. More American women organized against their own right to vote than in favor of it, until 1916. Anti-suffragism was associated with "domestic feminism," the belief that women had the right to complete freedom within the home. In the United States, these activists were often referred to as "remonstrants" or "antis."

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

Josephine Jewell Dodge was an American educator, an early leader of the day nursery movement, and an anti-suffrage activist.

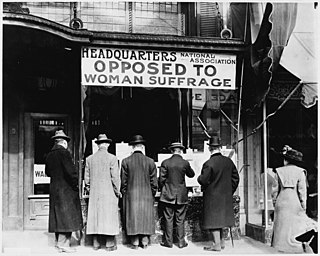

The National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage (NAOWS) was founded in the United States by women opposed to the suffrage movement in 1911. It was the most popular anti-suffrage organization in northeastern cities. NAOWS had influential local chapters in many states, including Texas and Virginia.

Mary Garrett Hay was an American suffragist and community organizer. She served as president of the Women's City Club of New York, the Woman Suffrage Party and the New York Equal Suffrage League. Hay was known for creating woman's suffrage groups across the country. She was also close to the notable suffragist, Carrie Chapman Catt, with one contemporary, Rachel Foster Avery, stating that Hay "really loves" Catt.

The Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women (MAOFESW) was one of the earliest organizations formed to oppose women's suffrage in the United States. The organization was founded in May of 1895. However, MAOFESW had its roots in earlier Massachusetts anti-suffrage groups and had a publication called The Remonstrance, started in 1890.

Bettina Borrmann Wells was a Bavarian-born English suffragette who toured the United States as an organizer and lecturer.

Women's suffrage efforts in Texas began in 1868 at the first Texas Constitutional Convention. In both Constitutional Conventions and subsequent legislative sessions, efforts to provide women the right to vote were introduced, only to be defeated. Early Texas suffragists such as Martha Goodwin Tunstall and Mariana Thompson Folsom worked with national suffrage groups in the 1870s and 1880s. It wasn't until 1893 and the creation of the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) by Rebecca Henry Hayes of Galveston that Texas had a statewide women's suffrage organization. Members of TERA lobbied politicians and political party conventions on women's suffrage. Due to an eventual lack of interest and funding, TERA was inactive by 1898. In 1903, women's suffrage organizing was revived by Annette Finnigan and her sisters. These women created the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in Houston in 1903. TESA sponsored women's suffrage speakers and testified on women's suffrage in front of the Texas Legislature. In 1908 and 1912, speaking tours by Anna Howard Shaw helped further renew interest in women's suffrage in Texas. TESA grew in size and suffragists organized more public events, including Suffrage Day at the Texas State Fair. By 1915, more and more women in Texas were supporting women's suffrage. The Texas Federation of Women's Clubs officially supported women's suffrage in 1915. Also that year, anti-suffrage opponents started to speak out against women's suffrage and in 1916, organized the Texas Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (TAOWS). TESA, under the political leadership of Minnie Fisher Cunningham and with the support of Governor William P. Hobby, suffragists began to make further gains in achieving their goals. In 1918, women achieved the right to vote in Texas primary elections. During the registration drive, 386,000 Texas women signed up during a 17-day period. An attempt to modify the Texas Constitution by voter referendum failed in May 1919, but in June 1919, the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment. Texas became the ninth state and the first Southern state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on June 28, 1919. This allowed white women to vote, but African American women still had trouble voting, with many turned away, depending on their communities. In 1923, Texas created white primaries, excluding all Black people from voting in the primary elections. The white primaries were overturned in 1944 and in 1964, Texas's poll tax was abolished. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed, promising that all people in Texas had the right to vote, regardless of race or gender.

Rosalie Loew Whitney was an American lawyer and suffragist.

Women's rights issues in Ohio were put into the public eye in the early 1850s. Women inspired by the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention created newspapers and then set up their own conventions, including the 1850 Ohio Women's Rights Convention which was the first women's right's convention outside of New York and the first that was planned and run solely by women. These early efforts towards women's suffrage affected people in other states and helped energize the women's suffrage movement in Ohio. Women's rights groups formed throughout the state, with the Ohio Women's Rights Association (OWRA) founded in 1853. Other local women's suffrage groups are formed in the late 1860s. In 1894, women won the right to vote in school board elections in Ohio. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was headquartered for a time in Warren, Ohio. Two efforts to vote on a constitutional amendment, one in 1912 and the other 1914 were unsuccessful, but drew national attention to women's suffrage. In 1916, women in East Cleveland gained the right to vote in municipal elections. A year later, women in Lakewood, Ohio and Columbus were given the right to vote in municipal elections. Also in 1917, the Reynolds Bill, which would allow women to vote in the next presidential election was passed, and then quickly repealed by a voter referendum sponsored by special-interest groups. On June 16, 1919, Ohio became the fifth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

The women's suffrage movement in Montana started while it was still a territory. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was an early organizer that supported suffrage in the state, arriving in 1883. Women were given the right to vote in school board elections and on tax issues in 1887. When the state constitutional convention was held in 1889, Clara McAdow and Perry McAdow invited suffragist Henry Blackwell to speak to the delegates about equal women's suffrage. While that proposition did not pass, women retained their right to vote in school and tax elections as Montana became a state. In 1895, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) came to Montana to organize local groups. Montana suffragists held a convention and created the Montana Woman's Suffrage Association (MWSA). Suffragists continued to organize, hold conventions and lobby the Montana Legislature for women's suffrage through the end of the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, Jeannette Rankin became a driving force around the women's suffrage movement in Montana. By January 1913, a women's suffrage bill had passed the Montana Legislature and went out as a referendum. Suffragists launched an all-out campaign leading up to the vote. They traveled throughout Montana giving speeches and holding rallies. They sent out thousands of letters and printed thousands of pamphlets and journals to hand out. Suffragists set up booths at the Montana State Fair and they held parades. Finally, after a somewhat contested election on November 3, 1914, the suffragists won the vote. Montana became one of eleven states with equal suffrage for most women. When the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, Montana ratified it on August 2, 1919. It wasn't until 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act that Native American women gained the right to vote.

The first women's suffrage group in Georgia, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA), was formed in 1892 by Helen Augusta Howard. Over time, the group, which focused on "taxation without representation" grew and earned the support of both men and women. Howard convinced the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold their first convention outside of Washington, D.C., in 1895. The convention, held in Atlanta, was the first large women's rights gathering in the Southern United States. GWSA continued to hold conventions and raise awareness over the next years. Suffragists in Georgia agitated for suffrage amendments, for political parties to support white women's suffrage and for municipal suffrage. In the 1910s, more organizations were formed in Georgia and the number of suffragists grew. In addition, the Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage also formed an organized anti-suffrage campaign. Suffragists participated in parades, supported bills in the legislature and helped in the war effort during World War I. In 1917 and 1919, women earned the right to vote in primary elections in Waycross, Georgia and in Atlanta respectively. In 1919, after the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land, women still had to wait to vote because of rules regarding voter registration. White Georgia women would vote statewide in 1922. Native American women and African-American women had to wait longer to vote. Black women were actively excluded from the women's suffrage movement in the state and had their own organizations. Despite their work to vote, Black women faced discrimination at the polls in many different forms. Georgia finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

The Anti-Sixteenth Amendment Society was an American anti-suffrage group in the late nineteenth century. It was formed in 1869. Madeleine Vinton Dahlgren was the leader and other prominent women were involved. Members of the group opposed giving women the right to vote and petitioned the United States Congress against women's suffrage.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Pennsylvania. Activists in the state began working towards women's rights in the early 1850s, when two women's rights conventions discussed women's suffrage. A statewide group, the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (PWSA), was formed in 1869. Other regional groups were formed throughout the state over the years. Suffragists in Pittsburgh created the "Pittsburgh Plan" in 1911. In 1915, a campaign to influence voters to support women's suffrage on the November 2 referendum took place. Despite these efforts, the referendum failed. On June 24, 1919, Pennsylvania became the seventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. Pennsylvania women voted for the first time on November 2, 1920.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in South Dakota. The early history of women's suffrage in the state is shared with North Dakota. When South Dakota became a state, it held a voter referendum in 1890 on an equal suffrage amendment. This effort failed, but suffragists continued to organize and lobby the legislature to pass voter referendums. None passed until 1918. South Dakota ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on December 4, 1919.

Efforts toward women's suffrage began early in Iowa's history. During the territory's Constitutional Convention, discussions on both African American and women's suffrage took place. Early on, women's rights were discussed in the state by women such as Amelia Bloomer and petitions for suffrage were sent to the Iowa state legislature. While African American men earned the right to vote in 1868, women from all backgrounds had to continue to agitate for enfranchisement. One of the first suffrage groups was formed in Dubuque in 1869. Not long after, a state suffrage convention was held in Mount Pleasant in 1870. Iowa suffragists focused on organizing and lobbying the state legislature. In 1894, women gained the right to vote on municipal bond and tax issues and also in school elections. These rights were immediately utilized by women who turned out in good numbers to vote on these issues. By the 1910s, the state legislature finally passed in successive sessions a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution. This resulted in a voter referendum to be held on the issue on June 5, 1916. The campaign included anti-suffrage agitation from liquor interests who claimed that women's suffrage would cause higher taxes. The amendment was defeated, though a subsequent investigation turned up a large amount of fraud. However, the election could not be invalidated and women had to wait to vote. On July 2, 1919, Iowa became the tenth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

Mary Kilbreth was an American anti-suffragist and an active member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She became president of the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) in 1919.