Related Research Articles

Short-term memory is the capacity for holding, but not manipulating, a small amount of information in mind in an active, readily available state for a short period of time. For example, short-term memory can be used to remember a phone number that has just been recited. The duration of short-term memory is believed to be in the order of seconds. A commonly cited capacity of items to remember is The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two. Cowan (2001) suggests that a more realistic figure is 4±1 items. In contrast, long-term memory holds information indefinitely.

Source amnesia is the inability to remember where, when or how previously learned information has been acquired, while retaining the factual knowledge. This branch of amnesia is associated with the malfunctioning of one's explicit memory. It is likely that the disconnect between having the knowledge and remembering the context in which the knowledge was acquired is due to a dissociation between semantic and episodic memory – an individual retains the semantic knowledge, but lacks the episodic knowledge to indicate the context in which the knowledge was gained.

The interference theory is a theory regarding human memory. Interference occurs in learning. The notion is that memories encoded in long-term memory (LTM) are forgotten and cannot be retrieved into short-term memory (STM) because either memory interferes with, or hampers the other. There is an immense number of encoded memories within the storage of LTM. The challenge for memory retrieval is recalling the specific memory and working in the temporary workspace provided in STM. Retaining information regarding the relevant time of encoding memories into LTM influences interference strength. There are two types of interference effects: proactive and retroactive interference.

The picture superiority effect refers to the phenomenon in which pictures and images are more likely to be remembered than are words. This effect has been demonstrated in numerous experiments using different methods. It is based on the notion that "human memory is extremely sensitive to the symbolic modality of presentation of event information". Explanations for the picture superiority effect are not concrete and are still being debated.

The spacing effect demonstrates that learning is more effective when study sessions are spaced out. This effect shows that more information is encoded into long-term memory by spaced study sessions, also known as spaced repetition or spaced presentation, than by massed presentation ("cramming").

The testing effect suggests long-term memory is increased when some of the learning period is devoted to retrieving information from memory. It is different from more general practice effect, defined in the APA Dictionary of Psychology as "any change or improvement that results from practice or repetition of task items or activities."

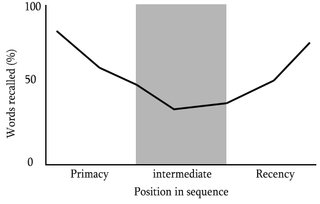

Serial-position effect is the tendency of a person to recall the first and last items in a series best, and the middle items worst. The term was coined by Hermann Ebbinghaus through studies he performed on himself, and refers to the finding that recall accuracy varies as a function of an item's position within a study list. When asked to recall a list of items in any order, people tend to begin recall with the end of the list, recalling those items best. Among earlier list items, the first few items are recalled more frequently than the middle items.

Baddeley's model of working memory is a model of human memory proposed by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974, in an attempt to present a more accurate model of primary memory. Working memory splits primary memory into multiple components, rather than considering it to be a single, unified construct.

The Levels of Processing model, created by Fergus I. M. Craik and Robert S. Lockhart in 1972, describes memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing. Deeper levels of analysis produce more elaborate, longer-lasting, and stronger memory traces than shallow levels of analysis. Depth of processing falls on a shallow to deep continuum. Shallow processing leads to a fragile memory trace that is susceptible to rapid decay. Conversely, deep processing results in a more durable memory trace.

Every day, people are presented with endless amounts of information, and in an effort to help keep track and organize this information, people must be able to recognize, differentiate and store information. One way to do that is to organize information as it pertains to the self. The overall concept of self-reference suggests that people interpret incoming information in relation to themselves, using their self-concept as a background for new information. Examples include being able to attribute personality traits to oneself or to identify recollected episodes as being personal memories of the past. The implications of self-referential processing are evident in many psychological phenomena. For example, the "cocktail party effect" notes that people attend to the sound of their names even during other conversation or more prominent, distracting noise. Also, people tend to evaluate things related to themselves more positively. For example, people tend to prefer their own initials over other letters. The self-reference effect (SRE) has received the most attention through investigations into memory. The concepts of self-referential encoding and the SRE rely on the notion that relating information to the self during the process of encoding it in memory facilitates recall, hence the effect of self-reference on memory. In essence, researchers have investigated the potential mnemonic properties of self-reference.

In psychology and neuroscience, memory span is the longest list of items that a person can repeat back in correct order immediately after presentation on 50% of all trials. Items may include words, numbers, or letters. The task is known as digit span when numbers are used. Memory span is a common measure of working memory and short-term memory. It is also a component of cognitive ability tests such as the WAIS. Backward memory span is a more challenging variation which involves recalling items in reverse order.

The generation effect is a phenomenon where information is better remembered if it is generated from one's own mind rather than simply read. Researchers have struggled to account for why generated information is better recalled than read information, but no single explanation has been sufficient.

The modality effect is a term used in experimental psychology, most often in the fields dealing with memory and learning, to refer to how learner performance depends on the presentation mode of studied items.

In psychology, context-dependent memory is the improved recall of specific episodes or information when the context present at encoding and retrieval are the same. In a simpler manner, "when events are represented in memory, contextual information is stored along with memory targets; the context can therefore cue memories containing that contextual information". One particularly common example of context-dependence at work occurs when an individual has lost an item in an unknown location. Typically, people try to systematically "retrace their steps" to determine all of the possible places where the item might be located. Based on the role that context plays in determining recall, it is not at all surprising that individuals often quite easily discover the lost item upon returning to the correct context. This concept is heavily related to the encoding specificity principle.

Emotion can have a powerful effect on humans and animals. Numerous studies have shown that the most vivid autobiographical memories tend to be of emotional events, which are likely to be recalled more often and with more clarity and detail than neutral events.

The effects of stress on memory include interference with a person's capacity to encode memory and the ability to retrieve information. During times of stress, the body reacts by secreting stress hormones into the bloodstream. Stress can cause acute and chronic changes in certain brain areas which can cause long-term damage. Over-secretion of stress hormones most frequently impairs long-term delayed recall memory, but can enhance short-term, immediate recall memory. This enhancement is particularly relative in emotional memory. In particular, the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and the amygdala are affected. One class of stress hormone responsible for negatively affecting long-term, delayed recall memory is the glucocorticoids (GCs), the most notable of which is cortisol. Glucocorticoids facilitate and impair the actions of stress in the brain memory process. Cortisol is a known biomarker for stress. Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus regulates the production of cortisol through negative feedback because it has many receptors that are sensitive to these stress hormones. However, an excess of cortisol can impair the ability of the hippocampus to both encode and recall memories. These stress hormones are also hindering the hippocampus from receiving enough energy by diverting glucose levels to surrounding muscles.

Memory supports and enables social interactions in a variety of ways. In order to engage in successful social interaction, people must be able to remember how they should interact with one another, whom they have interacted with previously, and what occurred during those interactions. There are a lot of brain processes and functions that go into the application and use of memory in social interactions, as well as psychological reasoning for its importance.

The encoding specificity principle is the general principle that matching the encoding contexts of information at recall assists in the retrieval of episodic memories. It provides a framework for understanding how the conditions present while encoding information relate to memory and recall of that information.

The self-reference effect is a tendency for people to encode information differently depending on whether they are implicated in the information. When people are asked to remember information when it is related in some way to themselves, the recall rate can be improved.

The Ranschburg effect, sometimes referred to as Ranschburg inhibition, is a psychological theory which refers to the substandard recall of repeated items, or listed items, in a short sequence. According to a 1973 paper in the Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, the Ranschburg effect is interpreted as a result of a restricted guessing strategy that excludes repetitions of remembered items as possible responses. This term is also described as the deterioration in memory performance when items are repeated in a list of items to be remembered. The Ranschburg effect can also be referred to as repetition inhibition, which should not be mistaken for repetition blindness, which refers to the failure or inability to recall repeated items from the short-term memory when sequences are presented rapidly.

References

- ↑ Brenner, Malcolm (1973). "The next-in-line effect" (PDF). Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 12 (3): 320–323. doi:10.1016/s0022-5371(73)80076-3. hdl: 2027.42/33869 .

- ↑ Bond Jr., Charles F; Omar, Adnan S (1990-05-01). "Social anxiety, state dependence, and the next-in-line effect". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 26 (3): 185–198. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(90)90034-J.

- 1 2 Bond, Charles F. (1985). "The next-in-line effect: Encoding or retrieval deficit?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 48 (4): 853–862. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.48.4.853.

- ↑ Walker, B. S.; Orr, F. E. (1976-12-01). "Anxiety and the next-in-line effect". Journal of Educational Psychology. 68 (6): 775–778. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.68.6.775. ISSN 1939-2176.