Existentialism is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the issue of human existence. Existentialist philosophers explore questions related to the meaning, purpose, and value of human existence. Common concepts in existentialist thought include existential crisis, dread, and anxiety in the face of an absurd world, as well as authenticity, courage, and virtue.

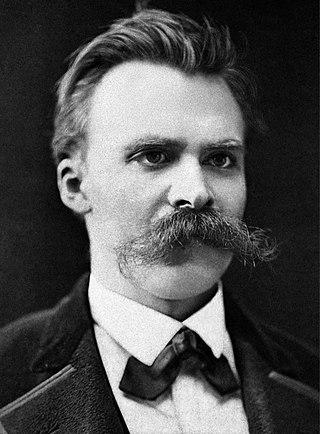

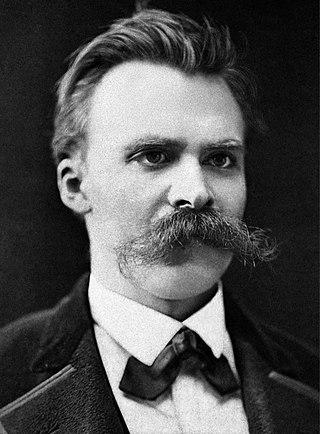

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer, whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy.

Existentialism Is a Humanism is a 1946 work by the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, based on a lecture by the same name he gave at Club Maintenant in Paris, on 29 October 1945. In early translations, Existentialism and Humanism was the title used in the United Kingdom; the work was originally published in the United States as Existentialism, and a later translation employs the original title.

Eternal return is a philosophical concept which states that time repeats itself in an infinite loop, and that exactly the same events will continue to occur in exactly the same way, over and over again, for eternity.

"God is dead" is a statement made by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. The first instance of this statement in Nietzsche's writings is in his 1882 The Gay Science, where it appears three times. The phrase also appears in Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits is a book by 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, originally published in 1878. A second part, Assorted Opinions and Maxims, was published in 1879, and a third part, The Wanderer and his Shadow, followed in 1880.

The Antichrist is a book by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, originally published in 1895. Although it was written in 1888, its content made Franz Overbeck and Heinrich Köselitz delay its publication, along with Ecce Homo. The German title can be translated into English as either The Anti-Christ or The Anti-Christian, depending on how the German word Christ is translated.

Walter Arnold Kaufmann was a German-American philosopher, translator, and poet. A prolific author, he wrote extensively on a broad range of subjects, such as authenticity and death, moral philosophy and existentialism, theism and atheism, Christianity and Judaism, as well as philosophy and literature. He served more than 30 years as a professor at Princeton University.

Alexander Nehamas is a Greek-born American philosopher. He is a professor of philosophy and comparative literature and the Edmund N. Carpenter II Class of 1943 Professor in the Humanities at Princeton University, where he has taught since 1990. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences and Member of the American Philosophical Society, the Academy of Athens since 2018. He works on Greek philosophy, aesthetics, Friedrich Nietzsche, Michel Foucault, and literary theory.

Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl was a German scholar best known for his studies of Plautus.

The Gay Science is a book by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1882, and followed by a second edition in 1887 after the completion of Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Beyond Good and Evil. This substantial expansion includes the addition of a fifth book to the existing four books of The Gay Science, as well as an appendix of songs. It was described by Nietzsche as "the most personal of all my books", and contains more poems than any of his other works.

Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is is the last original book written by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche before his death in 1900. It was written in 1888 and was not published until 1908.

The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy is a 1949 book about political economy by the French intellectual Georges Bataille, in which the author presents a new economic theory which he calls "general economy". The work comprises Volume I: Consumption, Volume II: The History of Eroticism, and Volume III: Sovereignty. It was first published in France by Les Éditions de Minuit, and in the United States by Zone Books. It is considered one of the most important of Bataille's books.

Philosophical Explanations is a 1981 metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical treatise by the philosopher Robert Nozick.

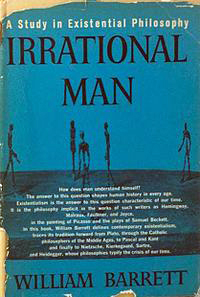

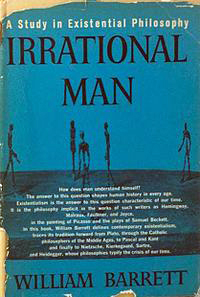

Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy is a 1958 book by the philosopher William Barrett, in which the author explains the philosophical background of existentialism and provides a discussion of several major existentialist thinkers, including Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, and Jean-Paul Sartre. Irrational Man helped to introduce existentialism to the English-speaking world and has been identified as one of the most useful books that discuss the subject, but Barrett has also been criticized for endorsing irrationality and for giving a distorted and misleading account of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

The revaluation of all values or transvaluation of all values is a concept from the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche.

My Sister and I is an apocryphal work attributed to the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Following the Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann, most consider the work to be a literary forgery, although a small minority argues for the book's authenticity.

Nietzsche and Philosophy is a 1962 book about Friedrich Nietzsche by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze, in which the author treats Nietzsche as a systematically coherent philosopher, discussing concepts such as the will to power and the eternal return. Nietzsche and Philosophy is a celebrated and influential work. Its publication has been seen as a significant turning-point in French philosophy, which had previously given little consideration to Nietzsche as a serious philosopher.

Ivan Soll is an American philosopher who is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the United States. He taught at UW from 1965 until his retirement in May 2011. His teaching and research focused on the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, German philosophy in general, existentialism, aesthetics, and various figures of continental philosophy.

Knowledge and Human Interests is a 1968 book by the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in which the author discusses the development of the modern natural and human sciences. He criticizes Sigmund Freud, arguing that psychoanalysis is a branch of the humanities rather than a science, and provides a critique of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.