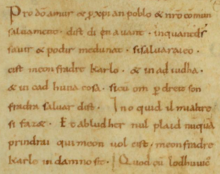

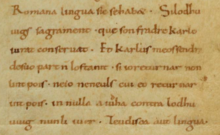

The Treaty of Verdun, agreed in August 843, divided the Frankish Empire into three kingdoms between Lothair I, Louis II and Charles II, the surviving sons of the emperor Louis I, the son and successor of Charlemagne. The treaty was concluded following almost three years of civil war and was the culmination of negotiations lasting more than a year. It was the first in a series of partitions contributing to the dissolution of the empire created by Charlemagne and has been seen as foreshadowing the formation of many of the modern countries of western Europe.

Louis the German, also known as Louis II of Germany, was the first king of East Francia, and ruled from 843 to 876 AD. Grandson of emperor Charlemagne and the third son of Louis the Pious, emperor of Francia, and his first wife, Ermengarde of Hesbaye, he received the appellation Germanicus shortly after his death, when East Francia became known as the kingdom of Germany.

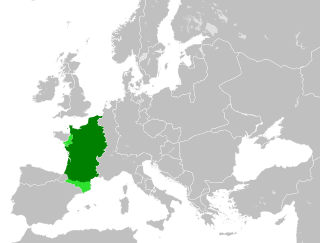

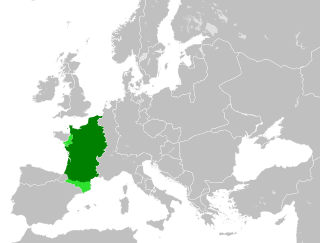

Charles the Bald, also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), King of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a series of civil wars during the reign of his father, Louis the Pious, Charles succeeded, by the Treaty of Verdun (843), in acquiring the western third of the empire. He was a grandson of Charlemagne and the youngest son of Louis the Pious by his second wife, Judith.

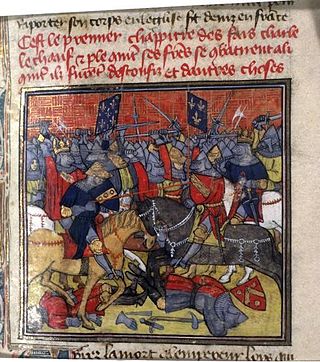

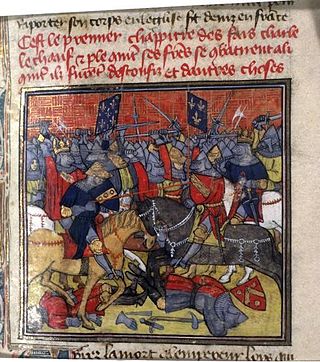

The three-year Carolingian Civil War culminated in the decisive Battle of Fontenoy, also called the Battle of Fontenoy-en-Puisaye, fought at Fontenoy, near Auxerre, on 25 June 841. The war was fought to decide the territorial inheritances of Charlemagne's grandsons—the division of the Carolingian Empire among the three surviving sons of Louis the Pious. Despite Louis' provisions for succession, war broke out between his sons and nephews. The battle has been described as a major defeat for the allied forces of Lothair I of Italy and Pepin II of Aquitaine, and a victory for Charles the Bald and Louis the German. Hostilities dragged on for another two years until the Treaty of Verdun, which had a major influence on subsequent European history.

Lothair I was a 9th-century Carolingian emperor and king of Italy (818–855) and Middle Francia (843–855).

The Treaty of Mersen or Meerssen, concluded on 8 August 870, was a treaty to partition the realm of Lothair II, known as Lotharingia, by his uncles Louis the German of East Francia and Charles the Bald of West Francia, the two surviving sons of Emperor Louis I the Pious. The treaty followed an earlier treaty of Prüm which had split Middle Francia between Lothair I's sons after his death in 855.

Teutberga was a queen of Lotharingia by marriage to Lothair II. She was a daughter of Bosonid Boso the Elder and sister of Hucbert, the lay-abbot of St. Maurice's Abbey.

Kingdom of Burgundy was a name given to various states located in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. The historical Burgundy correlates with the border area of France and Switzerland and includes the major modern cities of Geneva and Lyon.

The Kingdom of Burgundy, known from the 12th century as the Kingdom of Arles, also referred to in various context as Arelat, the Kingdom of Arles and Vienne, or Kingdom of Burgundy-Provence, was a realm established in 933 by the merger of the kingdoms of Upper and Lower Burgundy under King Rudolf II. It was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire in 1033 and from then on was one of the empire's three constituent realms, together with the Kingdom of Germany and the Kingdom of Italy. By the mid-13th century at the latest, however, it had lost its concrete political relevance.

In medieval historiography, West Francia or the Kingdom of the West Franks constitutes the initial stage of the Kingdom of France and extends from the year 843, from the Treaty of Verdun, to 987, the beginning of the Capetian dynasty. It was created from the division of the Carolingian Empire following the death of Louis the Pious, with its neighbor East Francia eventually evolving into the Kingdom of Germany.

Hugh or Hugo (802–844) was the illegitimate son of Charlemagne and his concubine Regina, with whom he had one other son: Bishop Drogo of Metz (801–855). Along with Drogo and his illegitimate half-brother Theodoric, Hugh was tonsured and sent from the palace of Aachen to a monastery in 818 by his father's successor, Louis the Pious, following the revolt of King Bernard of Italy. Hugh rose to become abbot of several abbacies: Saint-Quentin (822/23), Lobbes (836), and Saint-Bertin (836). In 834, he was made imperial archchancellor by his half-brother.

Middle Francia was a short-lived Frankish kingdom which was created in 843 by the Treaty of Verdun after an intermittent civil war between the grandsons of Charlemagne resulted in division of the united empire. Middle Francia was allocated to emperor Lothair I, the eldest son and successor of emperor Louis the Pious. His realm contained the imperial cities of Aachen and Pavia, but lacked any geographic or cultural cohesion, which prevented it from surviving and forming a nucleus of a larger state, as was the case with West Francia and East Francia.

Lièpvre is a commune in the Haut-Rhin department in Grand Est in north-eastern France. A monastery was built here in the eighth century by Saint Fulrad, who filled it with relics of Saint Cucuphas and Saint Alexander.

Guerin, Garin, Warin, or Werner was the Count of Auvergne, Chalon, Mâcon, Autun, Arles and Duke of Provence, Burgundy, and Toulouse. Guerin established the region against the Saracens from a base of Marseille and fortified Chalon-sur-Saône (834). He took part in many campaigns during the civil wars that marked the reign of Louis the Pious (814–840) and after his death until the Treaty of Verdun (843). The primary sources for his life are charters and chronicles like the Vita Hludovici.

Louis, a Frankish churchman and a member of the Carolingian royal family, was the Abbot of Saint-Denis from 841.

Gilbert (Giselbert), Count of Maasgau was a Frankish noble in what would become Lotharingia, during his lifetime in the 9th century. The Carolingian dynasty created this "middle kingdom" and fought over it, and he is mentioned as playing a role on both sides.

The Treaty of Prüm, concluded on 19 September 855, was the second of the partition treaties of the Carolingian Empire. As Emperor Lothair I was approaching death, he divided his realm of Middle Francia among his three sons.

Theutbald I was the bishop of Langres from when he was elected to succeed Alberic until his death. He is first securely attested as bishop in 842. He may have belonged to the same Bavarian family that had dominated the episcopate of Langres since 769.

Louis IV, called d'Outremer or Transmarinus, reigned as King of West Francia from 936 to 954. A member of the Carolingian dynasty, he was the only son of king Charles the Simple and his second wife Eadgifu of Wessex, daughter of King Edward the Elder of Wessex. His reign is mostly known thanks to the Annals of Flodoard and the later Historiae of Richerus.