Finno-Ugric is a traditional grouping of all languages in the Uralic language family except the Samoyedic languages. Its formerly commonly accepted status as a subfamily of Uralic is based on criteria formulated in the 19th century and is criticized by some contemporary linguists such as Tapani Salminen and Ante Aikio. The three most-spoken Uralic languages, Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian, are all included in Finno-Ugric.

Hungarian is a Uralic language spoken in Hungary and parts of several neighbouring countries that used to belong to it. It is the official language of Hungary and one of the 24 official languages of the European Union. Outside Hungary, it is also spoken by Hungarian communities in southern Slovakia, western Ukraine (Subcarpathia), central and western Romania (Transylvania), northern Serbia (Vojvodina), northern Croatia, northeastern Slovenia (Prekmurje), and eastern Austria.

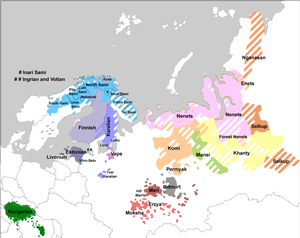

The Uralic languages form a language family of 42 languages spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers above 100,000 are Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt and Komi spoken in the European parts of the Russian Federation. Still smaller minority languages are Sámi languages of the northern Fennoscandia; other members of the Finnic languages, ranging from Livonian in northern Latvia to Karelian in northwesternmost Russia; and the Samoyedic languages, Mansi and Khanty spoken in Western Siberia.

Ural-Altaic, Uralo-Altaic, Uraltaic, or Turanic is a linguistic convergence zone and abandoned language-family proposal uniting the Uralic and the Altaic languages. It is generally now agreed that even the Altaic languages do not share a common descent: the similarities among Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic are better explained by diffusion and borrowing. Just as Altaic, internal structure of the Uralic family also has been debated since the family was first proposed. Doubts about the validity of most or all of the proposed higher-order Uralic branchings are becoming more common. The term continues to be used for the central Eurasian typological, grammatical and lexical convergence zone.

The Khanty, also known in older literature as Ostyaks are a Ugric Indigenous people, living in Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug, a region historically known as "Yugra" in Russia, together with the Mansi. In the autonomous okrug, the Khanty and Mansi languages are given co-official status with Russian. In the 2021 Census, 31,467 persons identified themselves as Khanty. Of those, 30,242 were resident in Tyumen Oblast, of whom 19,568 were living in Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug and 9,985—in Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. 495 were residents of neighbouring Tomsk Oblast, and 109 lived in Sverdlovsk Oblast.

The Mansi are an Ob-Ugric Indigenous people living in Khanty–Mansia, an autonomous okrug within Tyumen Oblast in Russia. In Khanty–Mansia, the Khanty and Mansi languages have co-official status with Russian. The Mansi language is one of the postulated Ugric languages of the Uralic family. The Mansi people were formerly known as the Voguls.

The Ugric or Ugrian languages are a proposed branch of the Uralic language family.

Nenets is a pair of closely related languages spoken in northern Russia by the Nenets people. They are often treated as being two dialects of the same language, but they are very different and mutual intelligibility is low. The languages are Tundra Nenets, which has a higher number of speakers, spoken by some 30,000 to 40,000 people in an area stretching from the Kanin Peninsula to the Yenisei River, and Forest Nenets, spoken by 1,000 to 1,500 people in the area around the Agan, Pur, Lyamin and Nadym rivers.

Karl (Kai) Reinhold Donner was a Finnish linguist, ethnographer and politician. He carried out expeditions to the Ob-Ugric and Samodeic peoples in Siberia 1911–1914 and was docent of Uralic languages at the University of Helsinki from 1924. He was, among other things, a pioneer of modern anthropological fieldwork methods, though his work is little known in the English-speaking world.

Proto-Uralic is the unattested reconstructed language ancestral to the modern Uralic language family. The hypothetical language is thought to have been originally spoken in a small area in about 7000–2000 BCE, and expanded to give differentiated Proto-Languages. Some newer research has pushed the "Proto-Uralic homeland" east of the Ural Mountains into Western Siberia.

Khanty, previously known as Ostyak, is a Uralic language spoken in the Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets Okrugs. There were thought to be around 7,500 speakers of Northern Khanty and 2,000 speakers of Eastern Khanty in 2010, with Southern Khanty being extinct since the early 20th century, however the total amount of speakers in the most recent census was around 13,900.

The Mansi languages are spoken by the Mansi people in Russia along the Ob River and its tributaries, in the Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug, and Sverdlovsk Oblast. Traditionally considered a single language, they constitute a branch of the Uralic languages, often considered most closely related to neighbouring Khanty and then to Hungarian.

Yugra or Iuhra was a collective name for lands and peoples in the region to the east of the northern Ural Mountains, in the Russian annals of the 12th–17th centuries. During this period the region was inhabited by the Khanty and Mansi (Voguls) peoples.

Historically, the Ugrians or Ugors were the linguistic ancestors of the present-day Hungarians, and the Khanty and Mansi peoples of Western Siberia. The name is sometimes also used in a modern context as a cover term for these three peoples. In 19th century and early 20th century literature, they were called Ugrian Finns.

A large minority of people in North Asia, particularly in Siberia, follow the religio-cultural practices of shamanism. Some researchers regard Siberia as the heartland of shamanism.

Hungarian is a Uralic language of the Ugric group. It has been spoken in the region of modern-day Hungary since the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in the late 9th century.

Hungarian shamanism is discovered through comparative methods in ethnology, designed to analyse and search ethnographic data of Hungarian folktales, songs, language, comparative cultures, and historical sources.

Elements of a Proto-Uralic religion can be recovered from reconstructions of the Proto-Uralic language.

The Volga Finns are a historical group of peoples living in the vicinity of the Volga, who speak Uralic languages. Their modern representatives are the Mari people, the Erzya and the Moksha Mordvins, as well as speakers of the extinct Merya, Muromian and Meshchera languages. The Permians are sometimes also grouped as Volga Finns.