Combined Arms is an approach to warfare which seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects. According to strategist William S. Lind, combined arms can be distinguished from the concept of "supporting arms" as follows:

Combined arms hits the enemy with two or more arms simultaneously in such a manner that the actions he must take to defend himself from one make him more vulnerable to another. In contrast, supporting arms is hitting the enemy with two or more arms in sequence, or if simultaneously, then in such combination that the actions the enemy must take to defend himself from one also defends himself from the other(s).

The Battle of Leuctra was a battle fought on 6 July 371 BC between the Boeotians led by the Thebans, and the Spartans along with their allies amidst the post-Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the neighbourhood of Leuctra, a village in Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae. The Theban victory shattered Sparta's immense influence over the Greek peninsula, which Sparta had gained with its victory in the Peloponnesian War a generation earlier.

The Battle of Rossbach took place on 5 November 1757 during the Third Silesian War near the village of Rossbach (Roßbach), in the Electorate of Saxony. It is sometimes called the Battle of, or at, Reichardtswerben, after a different nearby town. In this 90-minute battle, Frederick the Great, king of Prussia, defeated an Allied army composed of French forces augmented by a contingent of the Reichsarmee of the Holy Roman Empire. The French and Imperial army included 41,110 men, opposing a considerably smaller Prussian force of 22,000. Despite overwhelming odds, Frederick employed rapid movement, a flanking maneuver and oblique order to achieve complete surprise.

The Battle of Leuthen was fought on 5 December 1757 and involved Frederick the Great's Prussian Army using maneuver warfare and terrain to rout a larger Austrian force completely, which was commanded by Prince Charles of Lorraine and Count Leopold Joseph von Daun. The victory ensured Prussian control of Silesia during the Third Silesian War, which was part of the Seven Years' War.

A charge is an offensive maneuver in battle in which combatants advance towards their enemy at their best speed in an attempt to engage in a decisive close combat. The charge is the dominant shock attack and has been the key tactic and decisive moment of many battles throughout history. Modern charges usually involve small groups of fireteams equipped with weapons with a high rate of fire and striking against individual defensive positions, instead of large groups of combatants charging another group or a fortified line.

The Battle of Mollwitz was fought by Prussia and Austria on 10 April 1741, during the First Silesian War. It was the first battle of the new Prussian King Frederick II, in which both sides made numerous military blunders but the Prussian Army still managed to attain victory. This battle cemented Frederick's authority over the newly conquered territory of Silesia and gave him valuable military experience.

The Battle of Hohenfriedberg or Hohenfriedeberg, now Dobromierz, also known as the Battle of Striegau, now Strzegom, was one of Frederick the Great's most admired victories. Frederick's Prussian army decisively defeated an Austrian army under Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine on 4 June 1745 during the Second Silesian War.

The Second Battle of Mantinea was fought on July 4, 362 BC between the Thebans, led by Epaminondas and supported by the Arcadians and the Boeotian league against the Spartans, led by King Agesilaus II and supported by the Eleans, Athenians, and Mantineans. The battle was to determine which of the two alliances would dominate Greece. However, the death of Epaminondas and his intended successors coupled with the impact on the Spartans of yet another defeat weakened both alliances, and paved the way for Macedonian conquest led by Philip II of Macedon.

Maneuver warfare, or manoeuvre warfare, is a military strategy which attempts to defeat the enemy by incapacitating their decision-making through shock and disruption.

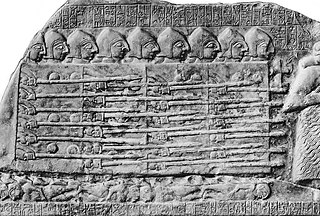

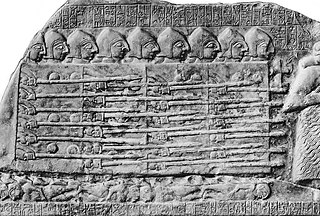

The phalanx was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar pole weapons. The term is particularly used to describe the use of this formation in Ancient Greek warfare, although the ancient Greek writers used it to also describe any massed infantry formation, regardless of its equipment. Arrian uses the term in his Array against the Alans when he refers to his legions. In Greek texts, the phalanx may be deployed for battle, on the march, or even camped, thus describing the mass of infantry or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They marched forward as one entity.

An infantry square, also known as a hollow square, was a historic combat formation in which an infantry unit formed in close order, usually when it was threatened with cavalry attack. As a traditional infantry unit generally formed a line to advance, more nimble cavalry could sweep around the end of the line and attack from the undefended rear or burst through the line, with much the same effect. By arranging the unit so that there was no undefended rear, a commander could organise an effective defense against a cavalry attack. With the development of modern firearms and the demise of cavalry, that formation is now considered obsolete.

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each choose to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A pitched battle is not a chance encounter such as a meeting engagement, or where one side is forced to fight at a time not of their choosing such as happens in a siege or an ambush. Pitched battles are usually carefully planned, to maximize one's strengths against an opponent's weaknesses, and use a full range of deceptions, feints, and other manoeuvres. They are also planned to take advantage of terrain favourable to one's force. Forces strong in cavalry for example will not select swamp, forest, or mountain terrain for the planned struggle. For example, Carthaginian general Hannibal selected relatively flat ground near the village of Cannae for his great confrontation with the Romans, not the rocky terrain of the high Apennines. Likewise, Zulu commander Shaka avoided forested areas or swamps, in favour of rolling grassland, where the encircling horns of the Zulu Impi could manoeuvre to effect. Pitched battles continued to evolve throughout history as armies implemented new technology and tactics.

Deep operation, also known as Soviet Deep Battle, was a military theory developed by the Soviet Union for its armed forces during the 1920s and 1930s. It was a tenet that emphasized destroying, suppressing or disorganizing enemy forces not only at the line of contact, but throughout the depth of the battlefield.

For much of history, humans have used some form of cavalry for war and, as a result, cavalry tactics have evolved over time. Tactically, the main advantages of cavalry over infantry troops were greater mobility, a larger impact, and a higher position.

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver is a movement of an armed force around an enemy force's side, or flank, to achieve an advantageous position over it. Flanking is useful because a force's fighting strength is typically concentrated in its front, therefore to circumvent an opposing force's front and attack its flank is to concentrate one's own offense in the area where the enemy is least able to concentrate defense.

The Royal Prussian Army served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The hammer and anvil is a military tactic involving the use of two primary forces, one to pin down an enemy, and the other to smash or defeat the opponent with an encirclement maneuver. It may involve a frontal assault by one part of the force, playing a slower-moving or more static role. The second phase involves a more mobile force that maneuvers around the enemy and attacks from behind or the flank to deliver a decisive blow. The "hammer and anvil" tactic is fundamentally a single envelopment, and is to be distinguished from a simple encirclement where one group simply keeps an enemy occupied, while a flanking force delivers the coup de grace. The strongest expression of the concept is where both echelons are sufficient in themselves to strike a decisive blow. The "anvil" echelon here is not a mere diversionary gambit, but a substantial body that hits the enemy hard to pin him down and grind away his strength. The "hammer" or maneuver element succeeds because the anvil force materially or substantially weakens the enemy, preventing him from adjusting to the threat in his flank or rear. Other variants of the concept allow for an enemy to be held fast by a substantial blocking or holding force, while a strong echelon, or hammer, delivers the decisive blow. In all scenarios, both the hammer and anvil elements are substantial entities that can cause significant material damage to opponents, as opposed to light diversionary, or small scale holding units.

Roman infantry tactics refers to the theoretical and historical deployment, formation, and manoeuvres of the Roman infantry from the start of the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver, or flanking manoeuvre, is an attack on the sides of an opposing force. If a flanking maneuver succeeds, the opposing force would be surrounded from two or more directions, which significantly reduces the maneuverability of the outflanked force and its ability to defend itself.