The Olmecs were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that the Olmecs derived in part from the neighboring Mokaya or Mixe–Zoque cultures.

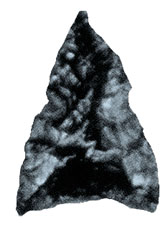

In archaeology, a prismatic blade is a long, narrow, specialized stone flake tool with a sharp edge, like a small razor blade. Prismatic blades are flaked from stone cores through pressure flaking or direct percussion. This process results in a very standardized finished tool and waste assemblage. The most famous and most prevalent prismatic blade material is obsidian, as obsidian use was widespread in Mesoamerica, though chert, flint, and chalcedony blades are not uncommon. The term is generally restricted to Mesoamerican archaeology, although some examples are found in the Old World, for example in a Minoan grave in Crete.

Kaminaljuyu is a Pre-Columbian site of the Maya civilization located in Guatemala City. Primarily occupied from 1500 BC to 1200 AD, it has been described as one of the greatest archaeological sites in the New World, although the extant remains are distinctly unimpressive. Debate continues about its size, integration, and role in the surrounding Valley of Guatemala and the Southern Maya area.

Mesoamerican chronology divides the history of prehispanic Mesoamerica into several periods: the Paleo-Indian ; the Archaic, the Preclassic or Formative (2500 BCE – 250 CE), the Classic (250–900 CE), and the Postclassic (900–1521 CE); as well as the post European contact Colonial Period (1521–1821), and Postcolonial, or the period after independence from Spain (1821–present).

In archaeology, a blade is a type of stone tool created by striking a long narrow flake from a stone core. This process of reducing the stone and producing the blades is called lithic reduction. Archaeologists use this process of flintknapping to analyze blades and observe their technological uses for historical purposes.

Mesoamerican pyramids form a prominent part of ancient Mesoamerican architecture. Although similar in some ways to Egyptian pyramids, these New World structures have flat tops and stairs ascending their faces. The largest pyramid in the world by volume is the Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the east-central Mexican state of Puebla. The builders of certain classic Mesoamerican pyramids have decorated them copiously with stories about the Hero Twins, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, Mesoamerican creation myths, ritualistic sacrifice, etc. written in the form of hieroglyphs on the rises of the steps of the pyramids, on the walls, and on the sculptures contained within.

The use of jade in Mesoamerica for symbolic and ideological ritual was highly influenced by its rarity and value among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Olmec, the Maya, and the various groups in the Valley of Mexico. Although jade artifacts have been created and prized by many Mesoamerican peoples, the Motagua River valley in Guatemala was previously thought to be the sole source of jadeite in the region.

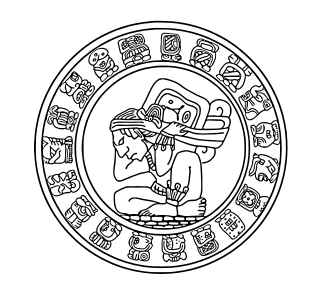

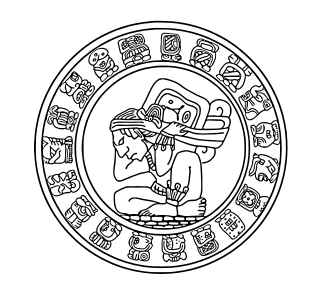

Bloodletting was the ritualized self-cutting or piercing of an individual's body that served a number of ideological and cultural functions within ancient Mesoamerican societies, in particular the Maya. When performed by ruling elites, the act of bloodletting was crucial to the maintenance of sociocultural and political structure. Bound within the Mesoamerican belief systems, bloodletting was used as a tool to legitimize the ruling lineage's socio-political position and, when enacted, was important to the perceived well-being of a given society or settlement.

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to most of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. In the pre-Columbian era many societies flourished in Mesoamerica for more than 3,000 years before the Spanish colonization of the Americas, begun at Hispaniola island in 1493. In world history, Mesoamerica was the site of two historical transformations: (i) primary urban generation, and (ii) the formation of New World cultures from the mixtures of the indigenous Mesoamerican peoples with the European, African, and Asian peoples who were introduced by the Spanish colonization of the Americas.

The geography of Mesoamerica describes the geographic features of Mesoamerica, a culture area in the Americas inhabited by complex indigenous pre-Columbian cultures exhibiting a suite of shared and common cultural characteristics. Several well-known Mesoamerican cultures include the Olmec, Teotihuacan, the Maya, the Aztec and the Purépecha. Mesoamerica is often subdivided in a number of ways. One common method, albeit a broad and general classification, is to distinguish between the highlands and lowlands. Another way is to subdivide the region into sub-areas that generally correlate to either culture areas or specific physiographic regions.

Trade in Maya civilization was a crucial factor in maintaining Maya cities.

Chunchucmil was once a large, sprawling pre-Columbian Maya city located in the western part of what is now the state of Yucatán, Mexico.

The causes and degree of Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures has been a subject of debate over many decades. Although the Olmecs are considered to be perhaps the earliest Mesoamerican civilization, there are questions concerning how and how much the Olmecs influenced cultures outside the Olmec heartland. This debate is succinctly, if simplistically, framed by the title of a 2005 The New York Times article: “Mother Culture, or Only a Sister?”.

The Feathered Serpent is a prominent supernatural entity or deity, found in many Mesoamerican religions. It is still called Quetzalcoatl among the Aztecs, Kukulkan among the Yucatec Maya, and Q'uq'umatz and Tohil among the K'iche' Maya.

The Southern Maya Area is a region of Pre-Columbian sites in Mesoamerica. It is long believed important to the rise of Maya civilization, during the period that is known as Preclassic. It lies within a broad arc going southeast from Chiapa de Corzo in Mexico to Copán and Chalchuapa, in Central America.

Balberta is a major Mesoamerican archaeological site on the Pacific coastal plain of southern Guatemala, belonging to the Maya civilization. It has been dated to the Early Classic period and is the only known major site on the Guatemalan Pacific coastal plain to have exposed Early Classic architecture that has not been buried under posterior Late Classic construction. The site was related to the nearby site of San Antonio, which lies 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) to the west.

The Preclassic period in Maya history stretches from the beginning of permanent village life c. 1000 BC until the advent of the Classic Period c. 250 AD, and is subdivided into Early, Middle, and Late. Major archaeological sites of this period include Nakbe, Uaxactun, Seibal, San Bartolo, Cival, and El Mirador.

The use of mirrors in Mesoamerican culture was associated with the idea that they served as portals to a realm that could be seen but not interacted with. Mirrors in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from the decorative to the divinatory. An ancient tradition among many Mesoamerican cultures was the practice of divination using the surface of a bowl of water as a mirror. At the time of the Spanish conquest this form of divination was still practiced among the Maya, Aztecs and Purépecha. In Mesoamerican art, mirrors are frequently associated with pools of liquid; this liquid was likely to have been water.

Economy is conventionally defined as a function for production and distribution of goods and services by multiple agents within a society and/or geographical place An economy is hierarchical, made up of individuals that aggregate to make larger organizations such as governments and gives value to goods and services. The Maya economy had no universal form of trade exchange other than resources and services that could be provided among groups such as cacao beans and copper bells. Though there is limited archeological evidence to study the trade of perishable goods, it is noteworthy to explore the trade networks of artifacts and other luxury items that were likely transported together.

The first forms of economic organization in Pre-Hispanic Mexico were agriculture and hunting activities. The first people who inhabited the Mexican lands and part of Central America were great builders and later on creators of some of the most advanced civilizations of that time. The economy of that time, however, was based on the commercial activities, the division of society into classes, and later the importance that was generated in the economy by the so-called Tlatoani of the Aztecs.