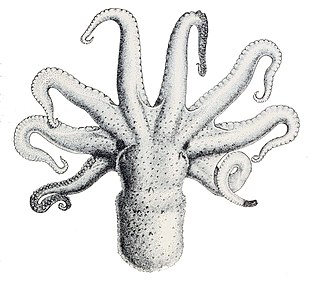

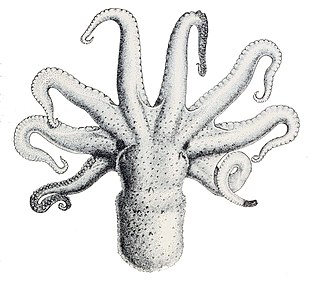

An octopus is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda. The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like other cephalopods, an octopus is bilaterally symmetric with two eyes and a beaked mouth at the center point of the eight limbs. The soft body can radically alter its shape, enabling octopuses to squeeze through small gaps. They trail their eight appendages behind them as they swim. The siphon is used both for respiration and for locomotion, by expelling a jet of water. Octopuses have a complex nervous system and excellent sight, and are among the most intelligent and behaviourally diverse of all invertebrates.

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting these criteria. Like all other cephalopods, squid have a distinct head, bilateral symmetry, and a mantle. They are mainly soft-bodied, like octopuses, but have a small internal skeleton in the form of a rod-like gladius or pen, made of chitin.

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, and a set of arms or tentacles modified from the primitive molluscan foot. Fishers sometimes call cephalopods "inkfish", referring to their common ability to squirt ink. The study of cephalopods is a branch of malacology known as teuthology.

Blue-ringed octopuses, comprising the genus Hapalochlaena, are four extremely venomous species of octopus that are found in tide pools and coral reefs in the Pacific and Indian oceans, from Japan to Australia. They can be identified by their yellowish skin and characteristic blue and black rings that change color dramatically when the animal is threatened. They eat small crustaceans, including crabs, hermit crabs, shrimp, other small sea animals.

The southern blue-ringed octopus is one of three highly venomous species of blue-ringed octopuses. It is most commonly found in tidal rock pools along the south coast of Australia. As an adult, it can grow up to 20 centimetres (8 in) long and on average weighs 26 grams (0.9 oz). They are normally a docile species, but they are highly venomous, possessing venom capable of killing humans. Their blue rings appear with greater intensity when they become aggravated or threatened.

Octopus is the largest genus of octopuses, comprising more than 100 species. These species are widespread throughout the world's oceans. Many species formerly placed in the genus Octopus are now assigned to other genera within the family. The octopus has 8 arms, averaging 20 cm long for an adult.

The giant Pacific octopus, also known as the North Pacific giant octopus, is a large marine cephalopod belonging to the genus Enteroctopus. Its spatial distribution includes the coastal North Pacific, along Mexico, The United States, Canada, Russia, Eastern China, Japan, and the Korean Peninsula. It can be found from the intertidal zone down to 2,000 m (6,600 ft), and is best adapted to cold, oxygen-rich water. It is the largest octopus species, based on a scientific record of a 71-kilogram (157-pound) individual weighed live.

Octopus cyanea, also known as the big blue octopus or day octopus, is an octopus in the family Octopodidae. It occurs in both the Pacific and Indian Oceans, from Hawaii to the eastern coast of Africa. O. cyanea grows to 16 cm in mantle length with arms to at least 80 cm. This octopus was described initially by the British zoologist John Edward Gray in 1849; the type specimen was collected off Australia and is at the Natural History Museum in London.

Cuttlefish or cuttles are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of buoyancy.

Macroctopus maorum is known more commonly as the Maori octopus or the New Zealand octopus. They can also be known as Pinnoctopus cordiformis, is found in the waters around New Zealand and southern Australia. M. maorum is one of the largest and most aggressive octopus species living in the New Zealand and Australian waters. They feed mainly on crustaceans and fish. Although they have a short life span, the females lay thousands of eggs and are very protective of them.

Sepioteuthis lessoniana, commonly known as the bigfin reef squid, glitter squid or oval squid, is a species of loliginid squid. It is one of the three currently recognized species belonging to the genus Sepioteuthis. Studies in 1993, however, have indicated that bigfin reef squids may comprise a cryptic species complex. The species is likely to include several very similar and closely related species.

Octopus chierchiae, commonly known as the lesser Pacific striped octopus or pygmy zebra octopus, is a species of octopus.

Abdopus aculeatus is a small octopus species in the order Octopoda. A. aculeatus has the common name of algae octopus due to its typical resting camouflage, which resembles a gastropod shell overgrown with algae. It is small in size with a mantle around the size of a small orange and arms 25 cm in length, and is adept at mimicking its surroundings.

Pinnoctopus cordiformis is a species of octopus found around the coasts of New Zealand.

Octopus maya, known colloquially as the Mexican four-eyed octopus, is a shallow water octopus that can be found in the tropical Western Atlantic Ocean. It is common to sea grass prairies and coral formations. The species was initially discovered in an octopus fishery in Campeche Mexico, where its close external resemblance to Octopus vulgaris led to its mistaken grouping with the other species. O. maya makes up 80% of octopus catch in the Yucatán Peninsula, while O. vulgaris makes up the remaining 20%.

The larger Pacific striped octopus (LPSO), or Harlequin octopus, is a species of octopus known for its intelligence and gregarious nature. The species was first documented in the 1970s and, being fairly new to scientific observation, has yet to be scientifically described. Because of this, LPSO has no official scientific name. Unlike other octopus species which are normally solitary, the LPSO has been reported as forming groups of up to 40 individuals. While most octopuses are cannibalistic and have to exercise extreme caution while mating, these octopuses mate with their ventral sides touching, pressing their beaks and suckers together in an intimate embrace. The LPSO has presented many behaviors that differ from most species of octopus, including intimate mating behaviors, formation of social communities, unusual hunting behavior, and the ability to reproduce multiple times throughout their life. The LPSO has been found to favor the tropical waters of the Eastern Pacific.

Wunderpus photogenicus, the wunderpus octopus, is a small-bodied species of octopus with distinct white and rusty brown coloration. 'Wunderpus' from German “wunder” meaning ‘marvel or wonder’.

Octopus bimaculatus, commonly referred to as Verill's two-spot octopus, is a similar species to the Octopus bimaculoides, a species it is often mistaken for. The two can be distinguished by the difference in the blue and black chain-like pattern of the ocelli. O. bimaculatus hunt and feed on a diverse number of benthic organisms that also reside off the coast of Southern California. Once the octopus reaches sexual maturity, it shortly dies after mating, which is approximately 12–18 months after hatching. Embryonic development tends to be rapid due to this short lifespan of these organisms.

Octopus insularis is a species of octopus described in 2008 from individuals found off the coast of Brazil, with a potentially much larger range.

Bathypolypus sponsalis, commonly called the globose octopus, is a deep sea cephalopod that can be found in both the eastern Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. It possesses many morphological traits adapted to a deep sea environment, including large eggs, reduced gills, no ink sac, and subgelatinous tissues. A distinguishing factor are the relatively large reproductive organs. Their diet consists of predominantly crustaceans and molluscs, but they sometimes consume fish as well. Bathypolypus sponsalis usually dies quickly after reproduction and only spawns once in their lifetime. Sexually mature females have a mantle length of at least 34 mm and sexually mature males have a mantle length of about 24 mm. Juveniles are white and transition to dark brown then to dark purple once maturity is reached.