Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was a French Neoclassical painter. Ingres was profoundly influenced by past artistic traditions and aspired to become the guardian of academic orthodoxy against the ascendant Romantic style. Although he considered himself a painter of history in the tradition of Nicolas Poussin and Jacques-Louis David, it is his portraits, both painted and drawn, that are recognized as his greatest legacy. His expressive distortions of form and space made him an important precursor of modern art, influencing Picasso, Matisse and other modernists.

Gustave Moreau was a French artist and an important figure in the Symbolist movement. Jean Cassou called him "the Symbolist painter par excellence". He was an influential forerunner of symbolism in the visual arts in the 1860s, and at the height of the symbolist movement in the 1890s, he was among the most significant painters. Art historian Robert Delevoy wrote that Moreau "brought symbolist polyvalence to its highest point in Jupiter and Semele." He was a prolific artist who produced over 15,000 paintings, watercolors, and drawings. Moreau painted allegories and traditional biblical and mythological subjects favored by the fine art academies. J. K. Huysmans wrote, "Gustave Moreau has given new freshness to dreary old subjects by a talent both subtle and ample: he has taken myths worn out by the repetitions of centuries and expressed them in a language that is persuasive and lofty, mysterious and new." The female characters from the Bible and mythology that he so frequently depicted came to be regarded by many as the archetypical symbolist woman. His art fell from favor and received little attention in the early 20th century but, beginning in the 1960s and 70s, he has come to be considered among the most paramount of symbolist painters.

A sphinx is a mythical creature with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle.

The Nabis were a group of young French artists active in Paris from 1888 until 1900, who played a large part in the transition from Impressionism and academic art to abstract art, symbolism and the other early movements of modernism. The members included Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, Édouard Vuillard, Ker-Xavier Roussel, Félix Vallotton, Paul Sérusier and Auguste Cazalis. Most were students at the Académie Julian in Paris in the late 1880s. The artists shared a common admiration for Paul Gauguin and Paul Cézanne and a determination to renew the art of painting, but varied greatly in their individual styles. They believed that a work of art was not a depiction of nature, but a synthesis of metaphors and symbols created by the artist. In 1900, the artists held their final exhibition and went their separate ways.

A figure painting is a work of fine art in any of the painting media with the primary subject being the human figure, whether clothed or nude. Figure painting may also refer to the activity of creating such a work. The human figure has been one of the constant subjects of art since the first Stone Age cave paintings, and has been reinterpreted in various styles throughout history.

Théodore Chassériau was a Dominican-born French Romantic painter noted for his portraits, historical and religious paintings, allegorical murals, and Orientalist images inspired by his travels to Algeria. Early in his career he painted in a Neoclassical style close to that of his teacher Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, but in his later works he was strongly influenced by the Romantic style of Eugène Delacroix. He was a prolific draftsman, and made a suite of prints to illustrate Shakespeare's Othello. The portrait he painted at the age of 15 of Prosper Marilhat makes Chassériau the youngest painter exhibited at the Louvre museum.

Marie Bracquemond was a French Impressionist artist. She was one of four notable women in the Impressionist movement, along with Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), and Eva Gonzalès (1847-1883). Bracquemond studied drawing as a child and began showing her work at the Paris Salon when she was still an adolescent. She never underwent formal art training, but she received limited instruction from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) and advice from Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) which contributed to her stylistic approach.

Fauvism is a style of painting and an art movement that emerged in France at the beginning of the 20th century. It was the style of les Fauves, a group of modern artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities and strong colour over the representational or realistic values retained by Impressionism. While Fauvism as a style began around 1904 and continued beyond 1910, the movement as such lasted only a few years, 1905–1908, and had three exhibitions. The leaders of the movement were André Derain and Henri Matisse.

Jupiter et Sémélé is a painting by the French Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau (1826–1898). It depicts a moment from the classical myth of the mortal woman Semele, mother of the god Dionysus, and her lover, Jupiter, the king of the gods. She was treacherously advised by the goddess Juno, Jupiter's wife, to ask him to appear to her in all his divine splendor. He obliged, but, in so doing, brought about her violent death by his divine thunder and lightning. The painting is a representation of "divinized physical love" and the overpowering experience that consumes Semele as the god appears in his supreme beauty which has been called "quite simply the most sumptuous expression imaginable of an orgasm".

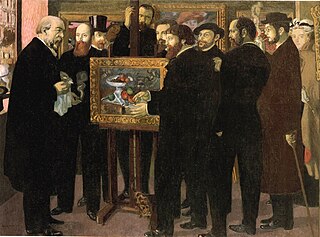

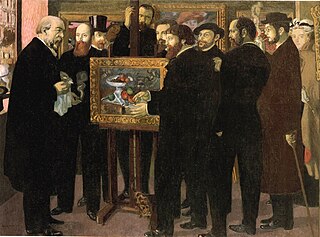

Homage to Cézanne is a painting in oil on canvas by the French artist Maurice Denis dating from 1900. It depicts a number of key figures from the once secret brotherhood of Les Nabis. The painting is a retrospective; by 1900 the group was breaking up as its members matured.

William Henry Herriman was an expatriate American art collector in Rome who, on his death, left important works of art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Brooklyn Museum.

The Apparition(French: L'Apparition) is a painting by French artist Gustave Moreau, painted between 1874 and 1876. It shows the biblical character of Salome dancing in front of Herod Antipas with a vision of John the Baptist's severed head. The 106 cm high and 72,2 cm wide watercolor held by the Musée d'Orsay in Paris elaborates on an episode told in the Matthew 14:6–11 and Mark 6:21–29. On a feast held for Herod Antipas' birthday, the princess Salome dances in front of the king and his guests. This pleased him so much he promises her anything she wished for. Incited by her mother Herodias, who was reproved by the John the Baptist for her illegitimate marriage to Herod, Salome demands John's head on a charger. Regretful but compelled to keep his word in front of everyone present, Herod complies with Salome's demand. John the Baptist is beheaded, his head brought on a charger and given to Salome, who in turn gives it to her mother.

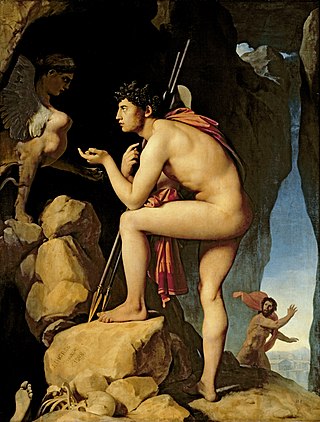

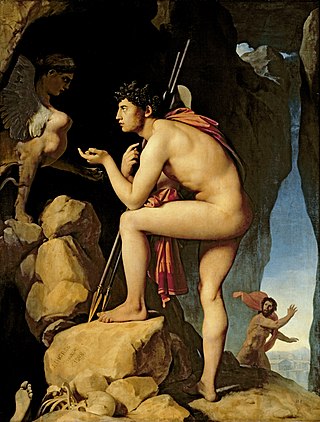

Oedipus and the Sphinx is a painting by the French Neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Originally a student work painted in 1808, it was enlarged and completed in 1827. The painting depicts Oedipus explaining the riddle of the Sphinx. An oil painting on canvas, it measures 189 x 144 cm, and is in the Louvre, which acquired it in 1878.

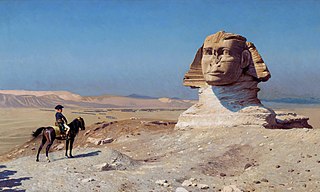

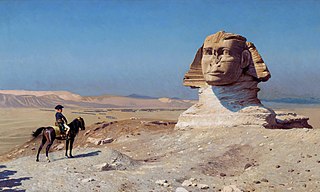

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx is an 1886 painting by the French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. It is also known as Oedipus (Œdipe). It depicts Napoleon Bonaparte during his Egyptian campaign, positioned on horseback in front of the Great Sphinx of Giza, with his army in the background.

Geneviève Lacambre is a French honorary general curator of heritage, and has been the Chargée de mission at the Musée d'Orsay.

Salome Dancing before Herod is an oil painting produced in 1876 by the French Symbolist artist Gustave Moreau. The subject matter is taken from the New Testament, depicting Salome—the daughter of Herod II and Herodias—dancing before Herod Antipas.

The Parisian Sphinx is an oil-on-canvas painting by Belgian painter Alfred Stevens. Painted between 1875 and 1877, it depicts a dreamy young woman gently supporting her head with her hand. The painting is part of the permanent collection of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp. The Parisian Sphinx shows the influence of Vermeer and the other Netherlandish old masters on Stevens, and testifies to the Symbolist influence in the latter's day. It incorporates a harmonious juxtaposition of superficial Dutch realism with the spreading Symbolist manner, as opposed to the bottom-up, pluralistic symbolism of the declining Romanticism.

Caress of the Sphinx is an 1896 painting by the Belgian Symbolist artist Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921) famed for its depiction of androgyny. The work is an interpretation of the French symbolist painter Gustave Moreau's 1864 painting Oedipus and the Sphinx.

Symbolist painting was one of the main artistic manifestations of symbolism, a cultural movement that emerged at the end of the 19th century in France and developed in several European countries. The beginning of this current was in poetry, especially thanks to the impact of The Flowers of Evil by Charles Baudelaire (1868), which powerfully influenced a generation of young poets including Paul Verlaine, Stéphane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud. The term "symbolism" was coined by Jean Moréas in a literary manifesto published in Le Figaro in 1886. The aesthetic premises of Symbolism moved from poetry to other arts, especially painting, sculpture, music and theater. The chronology of this style is difficult to establish: the peak is between 1885 and 1905, but already in the 1860s there were works pointing to symbolism, while its culmination can be established at the beginning of the First World War.

The Lady in White, also known as The Woman in White, is an 1880 oil-on-canvas painting by French artist Marie Bracquemond. It depicts the artist's half-sister Louise Quivoron, who often served as a model for her paintings. It was one of three paintings by Bracquemond shown at the fifth Impressionist exhibition in April 1880. A previous painting, Woman in the Garden (1877), may have been a study for The Lady in White. Like the other Impressionists of the time, Bracquemond worked outside en plein air, mostly in her garden at Sèvres.