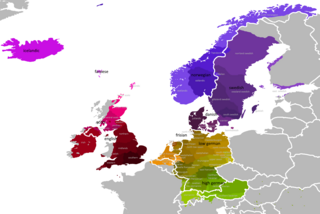

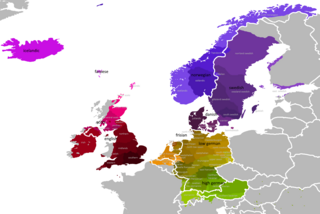

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, English, is also the world's most widely spoken language with an estimated 2 billion speakers. All Germanic languages are derived from Proto-Germanic, spoken in Iron Age Scandinavia and Germany.

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlements and chronologically coincides with the Viking Age, the Christianization of Scandinavia and the consolidation of Scandinavian kingdoms from about the 8th to the 15th centuries.

Old English, or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th century, and the first Old English literary works date from the mid-7th century. After the Norman Conquest of 1066, English was replaced for several centuries by Anglo-Norman as the language of the upper classes. This is regarded as marking the end of the Old English era, since during the subsequent period the English language was heavily influenced by Anglo-Norman, developing into what is now known as Middle English in England and Early Scots in Scotland.

The Germanic umlaut is a type of linguistic umlaut in which a back vowel changes to the associated front vowel (fronting) or a front vowel becomes closer to (raising) when the following syllable contains, , or.

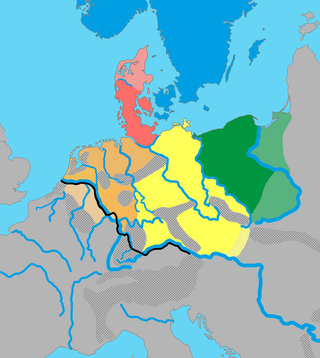

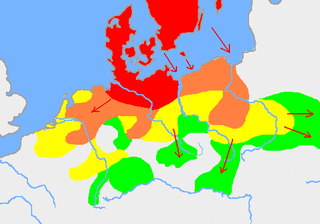

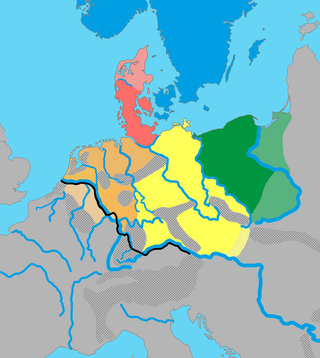

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic family of languages. The West Germanic branch is classically subdivided into three branches: Ingvaeonic, which includes English and the Frisian languages; Istvaeonic, which encompasses Dutch and its close relatives; and Irminonic, which includes German and its close relatives and variants.

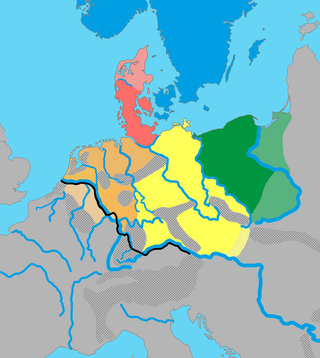

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Middle Dutch is a collective name for a number of closely related West Germanic dialects whose ancestor was Old Dutch. It was spoken and written between 1150 and 1500. Until the advent of Modern Dutch after 1500 or c. 1550, there was no overarching standard language, but all dialects were mutually intelligible. During that period, a rich Medieval Dutch literature developed, which had not yet existed during Old Dutch. The various literary works of the time are often very readable for speakers of Modern Dutch since Dutch is a rather conservative language.

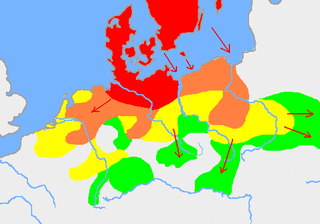

North Sea Germanic, also known as Ingvaeonic, is a postulated grouping of the northern West Germanic languages that consists of Old Frisian, Old English, and Old Saxon, and their descendants.

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, was a Germanic language and the earliest recorded form of Low German. It is a West Germanic language, closely related to the Anglo-Frisian languages. It is documented from the 8th century until the 12th century, when it gradually evolved into Middle Low German. It was spoken throughout modern northwestern Germany, primarily in the coastal regions and in the eastern Netherlands by Saxons, a Germanic tribe that inhabited the region of Saxony. It partially shares Anglo-Frisian's Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law which sets it apart from Low Franconian and Irminonic languages, such as Dutch, Luxembourgish and German.

Anglo-Saxon runes or Anglo-Frisian runes are runes that were used by the Anglo-Saxons and Medieval Frisians as an alphabet in their native writing system, recording both Old English and Old Frisian. Today, the characters are known collectively as the futhorc from the sound values of the first six runes. The futhorc was a development from the older co-Germanic 24-character runic alphabet, known today as Elder Futhark, expanding to 28-characters in its older form and up to 34-characters in its younger form. In contemporary Scandinavia, the Older Futhark developed into a shorter 16-character alphabet, today simply called Younger Futhark.

A-mutation is a metaphonic process supposed to have taken place in late Proto-Germanic.

West Germanic gemination was a sound change that took place in all West Germanic languages around the 3rd or 4th century AD. It affected consonants directly followed by, which were generally lengthened or geminated in that position. Because of Sievers' law, only consonants immediately after a short vowel were affected by the process.

The Anglo-Frisian languages are the Anglic and Frisian varieties of the West Germanic languages.

Old English phonology is necessarily somewhat speculative since Old English is preserved only as a written language. Nevertheless, there is a very large corpus of the language, and the orthography apparently indicates phonological alternations quite faithfully, so it is not difficult to draw certain conclusions about the nature of Old English phonology.

Like many other languages, English has wide variation in pronunciation, both historically and from dialect to dialect. In general, however, the regional dialects of English share a largely similar phonological system. Among other things, most dialects have vowel reduction in unstressed syllables and a complex set of phonological features that distinguish fortis and lenis consonants.

In linguistics, Old Dutch or Old Low Franconian is the set of dialects that evolved from Frankish spoken in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages, from around the 6th or 9th to the 12th century. Old Dutch is mostly recorded on fragmentary relics, and words have been reconstructed from Middle Dutch and Old Dutch loanwords in French.

Gothic is an extinct East Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other, mainly Romance, languages.

In historical linguistics, the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law is a description of a phonological development that occurred in the Ingvaeonic dialects of the West Germanic languages. This includes Old English, Old Frisian, and Old Saxon, and to a lesser degree Old Dutch.

The phonology of Old Saxon mirrors that of the other ancient Germanic languages, and also, to a lesser extent, that of modern West Germanic languages such as English, Dutch, Frisian, German, and Low German.

The phonological system of the Old English language underwent many changes during the period of its existence. These included a number of vowel shifts, and the palatalisation of velar consonants in many positions.