Related Research Articles

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavior, while cultural anthropology studies cultural meaning, including norms and values. A portmanteau term sociocultural anthropology is commonly used today. Linguistic anthropology studies how language influences social life. Biological or physical anthropology studies the biological development of humans.

In Melanesian and Polynesian cultures, mana is a supernatural force that permeates the universe. Anyone or anything can have mana. They believed it to be a cultivation or possession of energy and power, rather than being a source of power. It is an intentional force.

Bruno Latour was a French philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist. He was especially known for his work in the field of science and technology studies (STS). After teaching at the École des Mines de Paris from 1982 to 2006, he became professor at Sciences Po Paris (2006–2017), where he was the scientific director of the Sciences Po Medialab. He retired from several university activities in 2017. He was also a Centennial Professor at the London School of Economics.

Actor–network theory (ANT) is a theoretical and methodological approach to social theory where everything in the social and natural worlds exists in constantly shifting networks of relationships. It posits that nothing exists outside those relationships. All the factors involved in a social situation are on the same level, and thus there are no external social forces beyond what and how the network participants interact at present. Thus, objects, ideas, processes, and any other relevant factors are seen as just as important in creating social situations as humans.

Perspectivism is the epistemological principle that perception of and knowledge of something are always bound to the interpretive perspectives of those observing it. While perspectivism does not regard all perspectives and interpretations as being of equal truth or value, it holds that no one has access to an absolute view of the world cut off from perspective. Instead, all such viewing occurs from some point of view which in turn affects how things are perceived. Rather than attempt to determine truth by correspondence to things outside any perspective, perspectivism thus generally seeks to determine truth by comparing and evaluating perspectives among themselves. Perspectivism may be regarded as an early form of epistemological pluralism, though in some accounts includes treatment of value theory, moral psychology, and realist metaphysics.

The Achuar are an Indigenous people of the Americas belonging to the Jivaroan family, alongside the Shuar, Shiwiar, Awajun, and Wampis (Perú). They are settled along the banks of the Pastaza River, Huasaga River, and on the borders between Ecuador and Perú. The word "Achuar" originates from the name of the large palm trees called "Achu" that are abundant in the swamps within their territory.

Pierre Clastres was a French anthropologist, ethnographer, and ethnologist. He is best known for his contributions to the field of political anthropology, with his fieldwork among the Guayaki in Paraguay and his theory of stateless societies. An anarchist seeking an alternative to the hierarchized Western societies, he mostly researched Indigenous peoples of the Americas in which the power was not considered coercive and chieftains were powerless.

Anthropology of art is a sub-field in social anthropology dedicated to the study of art in different cultural contexts. The anthropology of art focuses on historical, economic and aesthetic dimensions in non-Western art forms, including what is known as 'tribal art'.

Cognitive anthropology is an approach within cultural anthropology and biological anthropology in which scholars seek to explain patterns of shared knowledge, cultural innovation, and transmission over time and space using the methods and theories of the cognitive sciences often through close collaboration with historians, ethnographers, archaeologists, linguists, musicologists, and other specialists engaged in the description and interpretation of cultural forms. Cognitive anthropology is concerned with what people from different groups know and how that implicit knowledge, in the sense of what they think subconsciously, changes the way people perceive and relate to the world around them.

Hauntology is a range of ideas referring to the return or persistence of elements from the social or cultural past, as in the manner of a ghost. The term is a neologism first introduced by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in his 1993 book Specters of Marx. It has since been invoked in fields such as visual arts, philosophy, electronic music, anthropology, politics, fiction, and literary criticism.

Philippe Descola, FBA is a French anthropologist noted for studies of the Achuar, one of several Jivaroan peoples, and for his contributions to anthropological theory.

Eduardo Batalha Viveiros de Castro is a Brazilian anthropologist and a professor at the National Museum of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

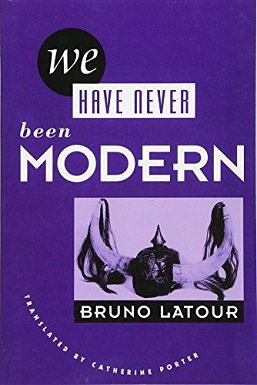

We Have Never Been Modern is a 1991 book by Bruno Latour, originally published in French as Nous n'avons jamais été modernes: Essai d'anthropologie symétrique.

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In the United States, social anthropology is commonly subsumed within cultural anthropology or sociocultural anthropology.

This bibliography of anthropology lists some notable publications in the field of anthropology, including its various subfields. It is not comprehensive and continues to be developed. It also includes a number of works that are not by anthropologists but are relevant to the field, such as literary theory, sociology, psychology, and philosophical anthropology.

Eduardo Kohn is Associate Professor of Anthropology at McGill University and winner of the 2014 Gregory Bateson Prize. He is best known for the book, How Forests Think.

Tony Lawson is a British philosopher and economist. He is professor of economics and philosophy in the Faculty of Economics at the University of Cambridge. He is a co-editor of the Cambridge Journal of Economics, a former director of the University of Cambridge Centre for Gender Studies, and co-founder of the Cambridge Realist Workshop and the Cambridge Social Ontology Group. Lawson is noted for his contributions to heterodox economics and to philosophical issues in social theorising, most especially to social ontology.

Epistemic cultures is a concept developed in the nineties by anthropologist Karin Knorr Cetina in her book Epistemic Cultures, how the sciences make knowledge. Opposed to a monist vision of scientific activity, Knorr Cetina defines the concept of epistemic cultures as a diversity of scientific activities according to different scientific fields, not only in methods and tools, but also in types of reasonings, ways to establish evidence, and relationships between theory and empiry. Knorr Cetina's work is seminal in questioning the so-called unity of science.

Nurit Bird-David is a professor of cultural anthropology at the University of Haifa, Israel. She is best known for her study of the Nayaka hunter-gatherers in South India, upon which she based much of her writings on animism, relational epistemology, and indigenous small-scale communities, and which later inspired additional fieldwork and insights on home-making in contemporary industrial societies, and the theoretical concept of scale in anthropology and other social sciences.

Political ontology is an approach within anthropology to understand the process of how practices, entities, and concepts come into being or are enacted. The field takes as its focus 'conflicts involving different assumptions about 'what exists,'" over metaphysical entities, how to understand ecosystems and environment, the nature of animals and plants, and how communities collectively adjudicate what is real. Political ontology emerged as part of the ontological turn, particularly in the works by Mario Blaser, Marisol de la Cadena and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Heywood, Paolo (2012). "Anthropology and What There Is: Reflections on 'Ontology'". The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology. University of Cambridge. 30 (1). doi:10.3167/ca.2012.300112. ISSN 0305-7674.

- ↑ The Development of Ontology from Suarez to Kant

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kohn, Eduardo (21 October 2015). "Anthropology of Ontologies". Annual Review of Anthropology . 44 (1): 311–327. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-014127. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ↑ Deleuze, Gilles; Guattari, Félix (1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816614011. OCLC 16472336.

- ↑ Carrithers, Michael; Candea, Matei; Sykes, Karen; Holbraad, Martin; Venkatesan, Soumhya (2010). "Ontology Is Just Another Word for Culture: Motion Tabled at the 2008 Meeting of the Group for Debates in Anthropological Theory, University of Manchester". Critique of Anthropology . 30 (2): 152–200. doi:10.1177/0308275X09364070. ISSN 0308-275X. S2CID 141506449.

- ↑ "Ontology | metaphysics". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ↑ Heidegger, Martin (1971). On the Way to Language (1st Harper & Row paperback ed.). San Francisco: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060638597. OCLC 7875767.

- ↑ "Definition of Ontology". Merriam-Webster . Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ↑ Holbraad, Martin; Pedersen, Morten Axel (2017). The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107103887. OCLC 985966648.

- ↑ "Ontology as the Major Theme of AAA 2013". Savage Minds. 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ↑ "About AAA - Connect with AAA". www.americananthro.org. American Anthropological Association . Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ↑ Price, David H. (2010). "Blogging Anthropology: Savage Minds, Zero Anthropology, and AAA Blogs". American Anthropologist . 112 (1): 140–142. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01203.x. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 20638767.

- ↑ "On Taking Ontological Turns". Savage Minds. 25 January 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ↑ Ries, Nancy (2009). "Potato Ontology: Surviving Postsocialism in Russia". Cultural Anthropology . 24 (2): 181–212. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2009.01129.x.

- ↑ Alberti, Benjamin; Fowles, Severin; Holbraad, Martin; Marshall, Yvonne; Witmore, Christopher (2011). ""Worlds Otherwise": Archaeology, Anthropology, and Ontological Difference" (PDF). Current Anthropology . 52 (6): 896–912. doi:10.1086/662027. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 67817305.

- ↑ Course, Magnus (2010). "Of Words and Fog: Linguistic Relativity and Amerindian Ontology". Anthropological Theory . 10 (3): 247–263. doi:10.1177/1463499610372177. ISSN 1463-4996. S2CID 146430306.

- ↑ de la Cadena, Marisol (2010). "Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual Reflections Beyond "Politics"". Cultural Anthropology . 25 (2): 334–370. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01061.x.

- ↑ Monaghan, John and Peter Just (2000). Social and Cultural Anthropology: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 13. ISBN 9780192853462.

- ↑ Kohn, Eduardo (2013). How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley. ISBN 9780520956865. OCLC 857079372.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Haraway, Donna Jeanne (2008). When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816654031. OCLC 191733419.

- ↑ Heywood, Paolo (19 May 2017). "The Ontological Turn". Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology . doi: 10.29164/17ontology .

- ↑ Bialecki, Jon (2016-06-20). "Turn, Turn, Turn". www.publicbooks.org/. Public Books.

- ↑ Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo (2011). "Zeno and the Art of Anthropology: Of Lies, Beliefs, Paradoxes, and Other Truths". Common Knowledge . Duke University Press. 17 (1): 128–145. doi:10.1215/0961754X-2010-045. ISSN 0961-754X. S2CID 145307160.

- 1 2 Descola, Philippe (1994). In the Society of Nature: A Native Ecology in Amazonia. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521411035. OCLC 27974392.

- 1 2 Descola, Philippe; Lloyd, Janet (2013). Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226145006. OCLC 855534400.

- ↑ Latour, Bruno (2013). An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 9780674724990. OCLC 826456727.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo; Skafish, Peter (2014). Cannibal Metaphysics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781937561970. OCLC 939262444.

- ↑ Descola, Philippe; Pálsson, Gísli (1996). Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780203451069. OCLC 1081429894.

- 1 2 3 Descola, Philippe (2014). "Modes of Being and Forms of Predication". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory . 4 (1): 271–280. doi:10.14318/hau4.1.012. ISSN 2575-1433. S2CID 145504956.

- ↑ Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo (1998). "Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute . 4 (3): 469–488. doi:10.2307/3034157. JSTOR 3034157.

- ↑ Latour, Bruno; Porter, Catherine (1993). We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-0674948389. OCLC 27894925.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Geismar, Haidy (2009). "On Multiple Ontologies and the Temporality of Things". Material World. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ↑ "Turn, Turn, Turn". Public Books . 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ↑ Charbonnier, Pierre; Salmon, Gildas; Skafish, Peter (2017). Comparative Metaphysics: Ontology After Anthropology. London. ISBN 9781783488575. OCLC 929123082.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Abramson, Allen; Holbraad, Martin. Framing Cosmologies: The Anthropology of Worlds. Manchester. ISBN 9781847799098. OCLC 953456922.

- ↑ Pedersen, Morten Axel (2012). Common Nonsense: A review of certain recent reviews of the 'ontological turn'. OCLC 842767912.

- 1 2 Rollason, William (June 2008). "Ontology – just another word for culture?". Anthropology Today . 24 (3): 28–31. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8322.2008.00593.x. ISSN 0268-540X.

- ↑ Bessire, Lucas; Bond, David (August 2014). "Ontological anthropology and the deferral of critique". American Ethnologist . 41 (3): 440–456. doi:10.1111/amet.12083.