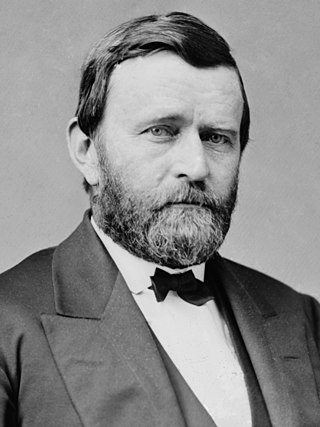

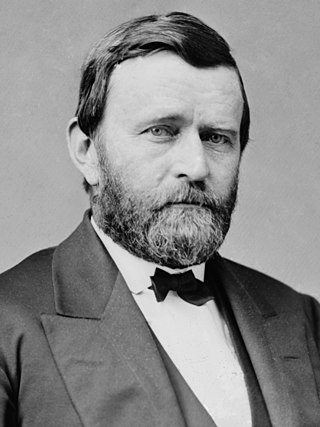

The 1868 United States presidential election was the 21st quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1868. In the first election of the Reconstruction Era, Republican nominee Ulysses S. Grant defeated Horatio Seymour of the Democratic Party. It was the first presidential election to take place after the conclusion of the American Civil War and the abolition of slavery. It was the first election in which African Americans could vote in the reconstructed Southern states, in accordance with the First Reconstruction Act.

The Reconstruction era was a period in United States history following the American Civil War, dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of abolishing slavery and reintegrating the former Confederate States of America into the United States. During this period, three amendments were added to the United States Constitution to grant equal civil rights to the newly freed slaves. Despite this, former Confederate states often used poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation to control people of color.

St. Landry Parish is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 82,540. The parish seat is Opelousas. The parish was established in 1807.

Opelousas is a small city and the parish seat of St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, United States. Interstate 49 and U.S. Route 190 were constructed with a junction here. According to the 2020 census, Opelousas has a population of 15,786, a 6.53 percent decline since the 2010 census, which had recorded a population of 16,634. Opelousas is the principal city for the Opelousas-Eunice Micropolitan Statistical Area, which had an estimated population of 80,808 in 2020. Opelousas is also the fourth largest city in the Lafayette-Acadiana Combined Statistical Area, which has a population of 537,947.

Washington is a village in St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 742 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Opelousas–Eunice Micropolitan Statistical Area. Washington was the largest inland port between New Orleans and St. Louis for much of the 19th century.

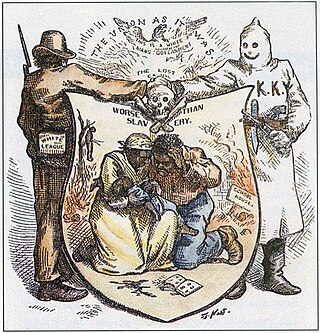

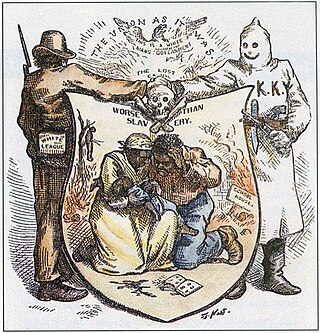

The Knights of the White Camelia was an American political terrorist organization that operated in the Southern United States in the late 19th century. Similar to and associated with the Ku Klux Klan, it supported White supremacy and opposed freedmen's rights.

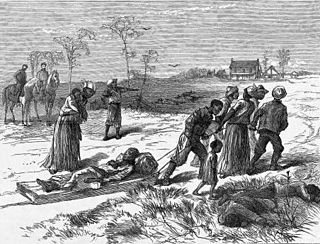

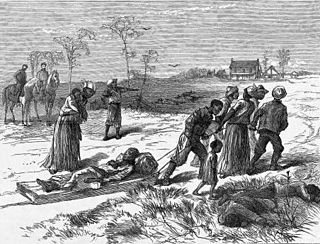

The Colfax massacre, sometimes referred to as the Colfax riot, occurred on Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, the parish seat of Grant Parish. An estimated 62–153 Black militia men were murdered while surrendering to a mob of former Confederate soldiers and members of the Ku Klux Klan. Three white men also died during the confrontation.

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white supremacist paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing, while also being supported by regional elements of the Democratic Party. Its first chapter was formed in Grant Parish, Louisiana, and neighboring parishes and was made up of many of the Confederate veterans who had participated in the Colfax massacre in April 1873. Chapters were soon founded in New Orleans and other areas of the state.

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the American Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce White supremacy. Their policy of Redemption was intended to oust the Radical Republicans, a coalition of freedmen, "carpetbaggers", and "scalawags". They were typically led by White yeomen and dominated Southern politics in most areas from the 1870s to 1910.

The Coushatta massacre (1874) was an attack by members of the White League, a white supremacist paramilitary organization composed of white Southern Democrats, on Republican officeholders and freedmen in Coushatta, the parish seat of Red River Parish, Louisiana. They assassinated six white Republicans and five to 20 freedmen who were witnesses.

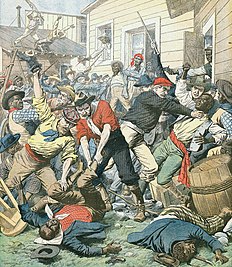

The New Orleans Massacre of 1866 occurred on July 30, when a peaceful demonstration of mostly Black Freedmen was set upon by a mob of white rioters, many of whom had been soldiers of the recently defeated Confederate States of America, leading to a full-scale massacre. The violence erupted outside the Mechanics Institute, site of a reconvened Louisiana Constitutional Convention. According to the official report, a total of 38 were killed and 146 wounded, of whom 34 dead and 119 wounded were Black Freedmen. Unofficial estimates were higher. Gilles Vandal estimated 40 to 50 Black Americans were killed and more than 150 Black Americans wounded. Others have claimed nearly 200 were killed. In addition, three white convention attendees were killed, as was one white protester.

The Louisiana Constitution is legally named the Constitution of the State of Louisiana and commonly called the Louisiana Constitution of 1974, and the Constitution of 1974. The constitution is the cornerstone of the law of Louisiana ensuring the rights of individuals, describing the distribution and power of state officials and local government, establishes the state and city civil service systems, creates and defines the operation of a state lottery, and the manner of revising the constitution.

Henry Clay Warmoth was an American attorney and veteran Civil War officer in the Union Army who was elected governor and state representative of Louisiana. A Republican, he was 26 years old when elected as 23rd Governor of Louisiana, one of the youngest governors elected in United States history. He served during the early Reconstruction Era, from 1868 to 1872.

The Republican Party of Louisiana(LAGOP) (French: Parti républicain de Louisiane, Spanish: Partido Republicano de Luisiana) is the affiliate of the Republican Party in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Its chair is Louis Gurvich, who was elected in 2018. It is currently the dominant party in the state, controlling all but one of Louisiana's six U.S. House seats, both U.S. Senate seats, all statewide executive offices, and both houses of the state legislature.

Michel Vidal was a U.S. Representative from Louisiana.

The Wheeler Compromise, sometimes known as the Wheeler Adjustment, was the settlement of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872 in the U.S. state of Louisiana, and negotiation to organize the state's legislature in January 1875. It was negotiated by, and named after, William A. Wheeler, Congressman from New York and a member of the U.S. House Committee on Southern Affairs. He later was elected as Vice President of the United States.

Alexandre Etienne de Clouet, also known as Alexandre Etienne de Clouet, Sr., was an American politician and sugar planter who was active in Louisiana politics both before and after the Civil War. During Reconstruction, he violently opposed Black suffrage, becoming a leader of the violent White League that attacked freedmen who attempted to vote.

Jean Maximilien Alcibiades Derneville DeBlanc was a lawyer and state legislator in Louisiana. He served as a colonel for the Confederate army during the American Civil War. Afterward, he founded the Knights of the White Camelia, a white insurgent militia that operated from 1867–1869 to suppress freedmen's voting, disrupt Republican Party political organizing and try to regain political control of the state government in the 1868 election. A Congressional investigation overturned 1868 election results in Louisiana.

Edmond Ducre Estilette, known as E. D. Estilette, was a politician and lawyer in Opelousas, Louisiana. He served in a number of public positions, most notably speaker of the Louisiana House of Representatives at the end of Reconstruction in 1875. Estilette oversaw the creation of one of the most infamous Black Codes of the post-Civil War era, but he was later seen as a moderating force in the turbulent politics of that era.

Alexander Fortune Riard, was a carpenter, merchant, lawyer and state legislator who served in the Louisiana State Senate from 1876 until 1878.