Botswana is a parliamentary republic in which the President of Botswana is both head of state and head of government. The nation's politics are based heavily on British parliamentary politics and on traditional Batswana chiefdom. The legislature is made up of the unicameral National Assembly and the advisory body of tribal chiefs, the Ntlo ya Dikgosi. The National Assembly chooses the president, but once in office the president has significant authority over the legislature with only limited separation of powers. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) rules as a dominant party; while elections in Botswana are considered free and fair by observers, the BDP has controlled the National Assembly since independence. Political opposition in Botswana often exists between factions in the BDP rather than through separate parties, though several opposition parties exist and regularly hold a small number of seats in the National Assembly.

Takeo Miki was a Japanese politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1974 until 1976.

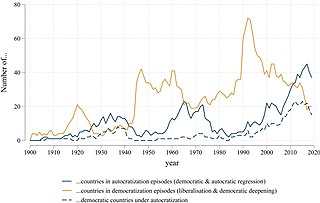

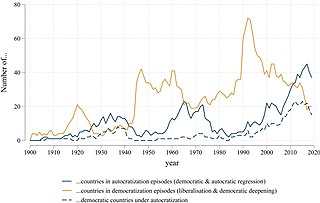

Democratization, or democratisation, is the democratic transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21 and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, it became the nation's dominant political worldview for a generation. The term itself was in active use by the 1830s.

In international relations, the liberal international order (LIO), also known as the rules-based international order (RBIO), or the rules-based order (RBO), describes a set of global, rule-based, structured relationships based on political liberalism, economic liberalism and liberal internationalism since the late 1940s. More specifically, it entails international cooperation through multilateral institutions and is constituted by human equality, open markets, security cooperation, promotion of liberal democracy, and monetary cooperation. The order was established in the aftermath of World War II, led in large part by the United States.

Proponents of "democratic peace theory" argue that both liberal and republican forms of democracy are hesitant to engage in armed conflict with other identified democracies. Different advocates of this theory suggest that several factors are responsible for motivating peace between democratic states. Individual theorists maintain "monadic" forms of this theory ; "dyadic" forms of this theory ; and "systemic" forms of this theory.

The iron law of oligarchy is a political theory first developed by the German-born Italian sociologist Robert Michels in his 1911 book Political Parties. It asserts that rule by an elite, or oligarchy, is inevitable as an "iron law" within any democratic organization as part of the "tactical and technical necessities" of the organization.

Political polarization is the divergence of political attitudes away from the center, towards ideological extremes.

A party system is a concept in comparative political science concerning the system of government by political parties in a democratic country. The idea is that political parties have basic similarities: they control the government, have a stable base of mass popular support, and create internal mechanisms for controlling funding, information and nominations.

An illiberal democracy describes a governing system that hides its "nondemocratic practices behind formally democratic institutions and procedures". There is a lack of consensus among experts about the exact definition of illiberal democracy or whether it even exists.

Democratic consolidation is the process by which a new democracy matures, in a way that it becomes unlikely to revert to authoritarianism without an external shock, and is regarded as the only available system of government within a country. A country can be described as consolidated when the current democratic system becomes “the only game in town”, meaning no one in the country is trying to act outside of the set institutions. This is the case when: no significant political group seriously attempts to overthrow the democratic regime, the democratic system is regarded as the most appropriate way to govern by the vast majority of the public, and all political actors are accustomed to the fact that conflicts are resolved through established political and constitutional rules.

General elections were held in Japan on 18 July 1993 to elect the 511 members of the House of Representatives. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which had been in power since 1955, lost their majority in the House. An eight-party coalition government was formed and headed by Morihiro Hosokawa, the leader of the Japan New Party (JNP). The election result was profoundly important to Japan's domestic and foreign affairs.

American political ideologies conventionally align with the left–right political spectrum, with most Americans identifying as conservative, liberal, or moderate. Contemporary American conservatism includes social conservatism, classical liberalism and economic liberalism. The former ideology developed as a response to communism and the civil rights movement, while the latter two ideologies developed as a response to the New Deal. Contemporary American liberalism includes progressivism, welfare capitalism and social liberalism, developing during the Progressive Era and the Great Depression. Besides modern conservatism and liberalism, the United States has a notable libertarian movement, developing during the mid-20th century as a revival of classical liberalism. Historical political movements in the United States have been shaped by ideologies as varied as republicanism, populism, separatism, fascism, socialism, monarchism, and nationalism.

Democracy promotion, also referred to as democracy building, can be domestic policy to increase the quality of already existing democracy or a strand of foreign policy adopted by governments and international organizations that seek to support the spread of democracy as a system of government. Among the reasons for supporting democracy include the belief that countries with a democratic system of governance are less likely to go to war, are likely to be economically better off and socially more harmonious. In democracy building, the process includes the building and strengthening of democracy, in particular the consolidation of democratic institutions, including courts of law, police forces, and constitutions. Some critics have argued that the United States has used democracy promotion to justify military intervention abroad.

Criticism of democracy has been a key part of democracy and its functions. Democracy has been criticized both by internal critics and external ones who reject the values embraced and nurtured by constitutional democracy.

Anocracy, or semi-democracy, is a form of government that is loosely defined as part democracy and part dictatorship, or as a "regime that mixes democratic with autocratic features". Another definition classifies anocracy as "a regime that permits some means of participation through opposition group behavior but that has incomplete development of mechanisms to redress grievances." The term "semi-democratic" is reserved for stable regimes that combine democratic and authoritarian elements. Scholars distinguish anocracies from autocracies and democracies in their capability to maintain authority, political dynamics, and policy agendas. Similarly, the regimes have democratic institutions that allow for nominal amounts of competition. Such regimes are particularly susceptible to outbreaks of armed conflict and unexpected or adverse changes in leadership. The United States of America are considered by some scholars to be an anocracy.

A hybrid regime is a type of political system often created as a result of an incomplete democratic transition from an authoritarian regime to a democratic one. Hybrid regimes are categorized as having a combination of autocratic features with democratic ones and can simultaneously hold political repressions and regular elections. Hybrid regimes are commonly found in developing countries with abundant natural resources such as petro-states. Although these regimes experience civil unrest, they may be relatively stable and tenacious for decades at a time. There has been a rise in hybrid regimes since the end of the Cold War.

Conservatism in Russia is a broad system of political beliefs in Russia that is characterized by support for Orthodox values, Russian imperialism, statism, economic interventionism, advocacy for the historical Russian sphere of influence, and a rejection of late modernist era Western culture.

Constructivism presumes that ethnic identities are shapeable and affected by politics. Through this framework, constructivist theories reassesses conventional political science dogmas. Research indicates that institutionalized cleavages and a multiparty system discourage ethnic outbidding and identification with tribal, localized groups. In addition, constructivism questions the widespread belief that ethnicity inherently inhibits national, macro-scale identification. To prove this point, constructivist findings suggest that modernization, language consolidation, and border-drawing, weakened the tendency to identify with micro-scale identity categories. One manifestation of ethnic politics gone awry, ethnic violence, is itself not seen as necessarily ethnic, since it attains its ethnic meaning as a conflict progresses.

Rational choice is a prominent framework in international relations scholarship. Rational choice is not a substantive theory of international politics, but rather a methodological approach that focuses on certain types of social explanation for phenomena. In that sense, it is similar to constructivism, and differs from liberalism and realism, which are substantive theories of world politics. Rationalist analyses have been used to substantiate realist theories, as well as liberal theories of international relations.