Keplerian elements

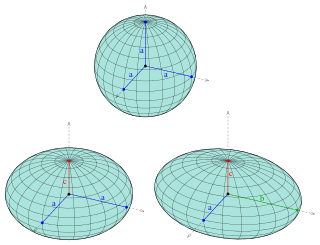

![In this diagram, the orbital plane (yellow) intersects a reference plane (gray). For Earth-orbiting satellites, the reference plane is usually the Earth's equatorial plane, and for satellites in solar orbits it is the ecliptic plane. The intersection is called the line of nodes, as it connects the reference body (the primary) with the ascending and descending nodes. The reference body and the vernal point ([?]) establish a reference direction and, together with the reference plane, they establish a reference frame. Orbit1.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/eb/Orbit1.svg/290px-Orbit1.svg.png)

The traditional orbital elements are the six Keplerian elements, after Johannes Kepler and his laws of planetary motion.

When viewed from an inertial frame, two orbiting bodies trace out distinct trajectories. Each of these trajectories has its focus at the common center of mass. When viewed from a non-inertial frame centered on one of the bodies, only the trajectory of the opposite body is apparent; Keplerian elements describe these non-inertial trajectories. An orbit has two sets of Keplerian elements depending on which body is used as the point of reference. The reference body (usually the most massive) is called the primary , the other body is called the secondary. The primary does not necessarily possess more mass than the secondary, and even when the bodies are of equal mass, the orbital elements depend on the choice of the primary.

Two elements define the shape and size of the ellipse:

- Eccentricity (e)—shape of the ellipse, describing how much it is elongated compared to a circle (not marked in diagram).

- Semi-major axis (a) — half the distance between the apoapsis and periapsis. The portion of the semi-major axis extending from the primary at one focus to the periapsis is shown as a purple line in the diagram; the rest (from the primary/focus to the center of the orbit ellipse) is below the reference plane and not shown.

Two elements define the orientation of the orbital plane in which the ellipse is embedded:

- Inclination (i) — vertical tilt of the ellipse with respect to the reference plane, measured at the ascending node (where the orbit passes upward through the reference plane, the green angle i in the diagram). Tilt angle is measured perpendicular to line of intersection between orbital plane and reference plane. Any three distinct points on an ellipse will define the ellipse orbital plane. The plane and the ellipse are both two-dimensional objects defined in three-dimensional space.

- Longitude of the ascending node (Ω) — horizontally orients the ascending node of the ellipse (where the orbit passes from south to north through the reference plane, symbolized by ☊) with respect to the reference frame's vernal point (symbolized by ♈︎). This is measured in the reference plane, and is shown as the green angle Ω in the diagram.

The remaining two elements are as follows:

- Argument of periapsis (ω) defines the orientation of the ellipse in the orbital plane, as an angle measured from the ascending node to the periapsis (the closest point the satellite body comes to the primary body around which it orbits), the purple angle ω in the diagram.

- True anomaly (ν, θ, or f) at epoch (t0) defines the position of the orbiting body along the ellipse at a specific time (the "epoch").

The mean anomaly M is a mathematically convenient fictitious "angle" which varies linearly with time, but which does not correspond to a real geometric angle. It can be converted into the true anomaly ν, which does represent the real geometric angle in the plane of the ellipse, between periapsis (closest approach to the central body) and the position of the orbiting body at any given time. Thus, the true anomaly is shown as the red angle ν in the diagram, and the mean anomaly is not shown.

The angles of inclination, longitude of the ascending node, and argument of periapsis can also be described as the Euler angles defining the orientation of the orbit relative to the reference coordinate system.

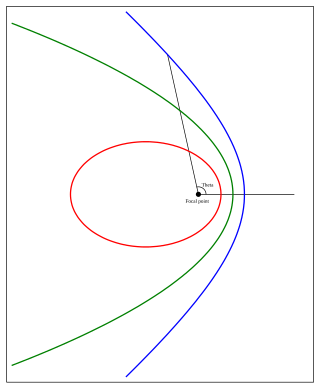

Note that non-elliptic trajectories also exist, but are not closed, and are thus not orbits. If the eccentricity is greater than one, the trajectory is a hyperbola. If the eccentricity is equal to one and the angular momentum is zero, the trajectory is radial. If the eccentricity is one and there is angular momentum, the trajectory is a parabola.

Required parameters

Given an inertial frame of reference and an arbitrary epoch (a specified point in time), exactly six parameters are necessary to unambiguously define an arbitrary and unperturbed orbit.

This is because the problem contains six degrees of freedom. These correspond to the three spatial dimensions which define position (x, y, z in a Cartesian coordinate system), plus the velocity in each of these dimensions. These can be described as orbital state vectors, but this is often an inconvenient way to represent an orbit, which is why Keplerian elements are commonly used instead.

Sometimes the epoch is considered a "seventh" orbital parameter, rather than part of the reference frame.

If the epoch is defined to be at the moment when one of the elements is zero, the number of unspecified elements is reduced to five. (The sixth parameter is still necessary to define the orbit; it is merely numerically set to zero by convention or "moved" into the definition of the epoch with respect to real-world clock time.)

Alternative parametrizations

Keplerian elements can be obtained from orbital state vectors (a three-dimensional vector for the position and another for the velocity) by manual transformations or with computer software. [1]

Other orbital parameters can be computed from the Keplerian elements such as the period, apoapsis, and periapsis. (When orbiting the Earth, the last two terms are known as the apogee and perigee.) It is common to specify the period instead of the semi-major axis in Keplerian element sets, as each can be computed from the other provided the standard gravitational parameter, GM, is given for the central body.

Instead of the mean anomaly at epoch, the mean anomaly M, mean longitude, true anomaly ν0, or (rarely) the eccentric anomaly might be used.

Using, for example, the "mean anomaly" instead of "mean anomaly at epoch" means that time t must be specified as a seventh orbital element. Sometimes it is assumed that mean anomaly is zero at the epoch (by choosing the appropriate definition of the epoch), leaving only the five other orbital elements to be specified.

Different sets of elements are used for various astronomical bodies. The eccentricity, e, and either the semi-major axis, a, or the distance of periapsis, q, are used to specify the shape and size of an orbit. The longitude of the ascending node, Ω, the inclination, i, and the argument of periapsis, ω, or the longitude of periapsis, ϖ, specify the orientation of the orbit in its plane. Either the longitude at epoch, L0, the mean anomaly at epoch, M0, or the time of perihelion passage, T0, are used to specify a known point in the orbit. The choices made depend whether the vernal equinox or the node are used as the primary reference. The semi-major axis is known if the mean motion and the gravitational mass are known. [2] [3]

It is also quite common to see either the mean anomaly (M) or the mean longitude (L) expressed directly, without either M0 or L0 as intermediary steps, as a polynomial function with respect to time. This method of expression will consolidate the mean motion (n) into the polynomial as one of the coefficients. The appearance will be that L or M are expressed in a more complicated manner, but we will appear to need one fewer orbital element.

Mean motion can also be obscured behind citations of the orbital period P.[ clarification needed ]

| Object | Elements used |

|---|---|

| Major planet | e, a, i, Ω, ϖ, L0 |

| Comet | e, q, i, Ω, ω, T0 |

| Asteroid | e, a, i, Ω, ω, M0 |

| Two-line elements | e, i, Ω, ω, n, M0 |

Euler angle transformations

The angles Ω, i, ω are the Euler angles (corresponding to α, β, γ in the notation used in that article) characterizing the orientation of the coordinate system

where:

- Î, Ĵ is in the equatorial plane of the central body. Î is in the direction of the vernal equinox. Ĵ is perpendicular to Î and with Î defines the reference plane. K̂ is perpendicular to the reference plane. Orbital elements of bodies (planets, comets, asteroids, ...) in the Solar System usually the ecliptic as that plane.

- x̂, ŷ are in the orbital plane and with x̂ in the direction to the pericenter (periapsis). ẑ is perpendicular to the plane of the orbit. ŷ is mutually perpendicular to x̂ and ẑ.

Then, the transformation from the Î, Ĵ, K̂ coordinate frame to the x̂, ŷ, ẑ frame with the Euler angles Ω, i, ω is:

where

The inverse transformation, which computes the 3 coordinates in the I-J-K system given the 3 (or 2) coordinates in the x-y-z system, is represented by the inverse matrix. According to the rules of matrix algebra, the inverse matrix of the product of the 3 rotation matrices is obtained by inverting the order of the three matrices and switching the signs of the three Euler angles.

That is,

where

The transformation from x̂, ŷ, ẑ to Euler angles Ω, i, ω is:

where arg(x,y) signifies the polar argument that can be computed with the standard function atan2(y,x) available in many programming languages.