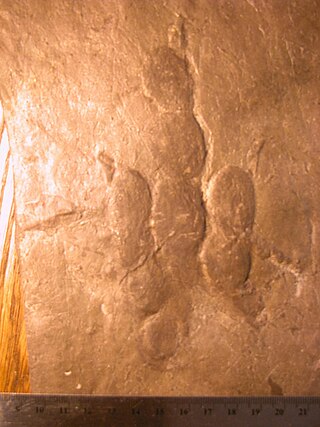

Dilophosaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaurs that lived in what is now North America during the Early Jurassic, about 186 million years ago. Three skeletons were discovered in northern Arizona in 1940, and the two best preserved were collected in 1942. The most complete specimen became the holotype of a new species in the genus Megalosaurus, named M. wetherilli by Samuel P. Welles in 1954. Welles found a larger skeleton belonging to the same species in 1964. Realizing it bore crests on its skull, he assigned the species to the new genus Dilophosaurus in 1970, as Dilophosaurus wetherilli. The genus name means "two-crested lizard", and the species name honors John Wetherill, a Navajo councilor. Further specimens have since been found, including an infant. Fossil footprints have also been attributed to the animal, including resting traces. Another species, Dilophosaurus sinensis from China, was named in 1993, but was later found to belong to the genus Sinosaurus.

Anchisaurus is a genus of basal sauropodomorph dinosaur. It lived during the Early Jurassic Period, and its fossils have been found in the red sandstone of the Upper Portland Formation, Northeastern United States, which was deposited from the Hettangian age into the Sinemurian age, between about 200 and 192 million years ago. Until recently it was classed as a member of Prosauropoda. The genus name Anchisaurus comes from the Greek αγχιanchi-; "near, close" + Greek σαυρος ; "lizard". Anchisaurus was coined as a replacement name for "Amphisaurus", which was itself a replacement name for Hitchcock's "Megadactylus", both of which had already been used for other animals.

Podokesaurus is a genus of coelophysoid dinosaur that lived in what is now the eastern United States during the Early Jurassic Period. The first fossil was discovered by the geologist Mignon Talbot near Mount Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1910. The specimen was fragmentary, preserving much of the body, limbs, and tail. In 1911, Talbot described and named the new genus and species Podokesaurus holyokensis based on it. The full name can be translated as "swift-footed lizard of Holyoke". This discovery made Talbot the first woman to find and describe a non-bird dinosaur. The holotype fossil was recognized as significant and was studied by other researchers, but was lost when the building it was kept in burned down in 1917; no unequivocal Podokesaurus specimens have since been discovered. It was made state dinosaur of Massachusetts in 2022.

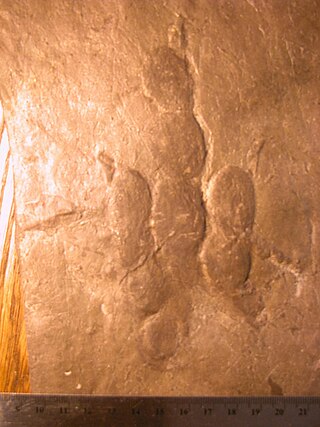

Grallator ["GRA-luh-tor"] is an ichnogenus which covers a common type of small, three-toed print made by a variety of bipedal theropod dinosaurs. Grallator-type footprints have been found in formations dating from the Early Triassic through to the early Cretaceous periods. They are found in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, Brazil and China, but are most abundant on the east coast of North America, especially the Triassic and Early Jurassic formations of the northern part of the Newark Supergroup. The name Grallator translates into "stilt walker", although the actual length and form of the trackmaking legs varied by species, usually unidentified. The related term "Grallae" is an ancient name for the presumed group of long-legged wading birds, such as storks and herons. These footprints were given this name by their discoverer, Edward Hitchcock, in 1858.

The Connecticut River Valley trackways are the fossilised footprints of a number of Early Jurassic dinosaurs or other archosauromorphs from the sandstone beds of Massachusetts and Connecticut. The finding has the distinction of being among the first known discoveries of dinosaur remains in North America.

Eubrontes is the name of fossilised dinosaur footprints dating from the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. They have been identified from France, Poland, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Australia (Queensland), US, India, China and Brazil (South).

Dinosaur State Park and Arboretum is a state-owned natural history preserve occupying 80 acres (32 ha) in the town of Rocky Hill, Connecticut. The state park protects one of the largest dinosaur track sites in North America. The park was created in recognition of fossil trackways embedded in sandstone from the beginning of the Jurassic period, about 200 million years ago. The facility is managed by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.

New Chum is a suburb in the City of Ipswich, Queensland, Australia. In the 2016 census, New Chum had a population of 0 people.

The Blackstone Formation is a geologic formation of the Ipswich Coal Measures Group in southeastern Queensland, Australia, dating to the Carnian to Norian stages of the Late Triassic. The shales, siltstones, coal and tuffs were deposited in a lacustrine environment. The Blackstone Formation contains the Denmark Hill Insect Bed.

Stegomosuchus is an extinct genus of small protosuchian crocodyliform. It is known from a single incomplete specimen discovered in the late 19th century in Lower Jurassic rocks of south-central Massachusetts, United States. It was originally thought to be a species of Stegomus, an aetosaur, but was eventually shown to be related to Protosuchus and thus closer to the ancestry of crocodilians. Stegomosuchus is also regarded as a candidate for the maker of at least some of the tracks named Batrachopus in the Connecticut River Valley.

The Montemarcello Formation is a Late Triassic (Carnian) geologic formation in Liguria, Italy. Fossil prosauropod tracks have been reported from the formation.

Paleontology in Connecticut refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Connecticut. Apart from its famous dinosaur tracks, the fossil record in Connecticut is relatively sparse. The oldest known fossils in Connecticut date back to the Triassic period. At the time, Pangaea was beginning to divide and local rift valleys became massive lakes. A wide variety of vegetation, invertebrates and reptiles are known from Triassic Connecticut. During the Early Jurassic local dinosaurs left behind an abundance of footprints that would later fossilize.

Paleontology in Utah refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Utah. Utah has a rich fossil record spanning almost all of the geologic column. During the Precambrian, the area of northeastern Utah now occupied by the Uinta Mountains was a shallow sea which was home to simple microorganisms. During the early Paleozoic Utah was still largely covered in seawater. The state's Paleozoic seas would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, fishes, and trilobites. During the Permian the state came to resemble the Sahara desert and was home to amphibians, early relatives of mammals, and reptiles. During the Triassic about half of the state was covered by a sea home to creatures like the cephalopod Meekoceras, while dinosaurs whose footprints would later fossilize roamed the forests on land. Sand dunes returned during the Early Jurassic. During the Cretaceous the state was covered by the sea for the last time. The sea gave way to a complex of lakes during the Cenozoic era. Later, these lakes dissipated and the state was home to short-faced bears, bison, musk oxen, saber teeth, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. Formally trained scientists have been aware of local fossils since at least the late 19th century. Major local finds include the bonebeds of Dinosaur National Monument. The Jurassic dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis is the Utah state fossil.

The Nugget Sandstone is a Late Triassic to Early Jurassic geologic formation that outcrops in Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah, western United States.

The Tomanová Formation is a Late Triassic geologic formation in Poland and Slovakia. Fossil theropod tracks have been reported from the formation.

The 20th century in ichnology refers to advances made between the years 1900 and 1999 in the scientific study of trace fossils, the preserved record of the behavior and physiological processes of ancient life forms, especially fossil footprints. Significant fossil trackway discoveries began almost immediately after the start of the 20th century with the 1900 discovery at Ipolytarnoc, Hungary of a wide variety of bird and mammal footprints left behind during the early Miocene. Not long after, fossil Iguanodon footprints were discovered in Sussex, England, a discovery that probably served as the inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World.

The 19th century in ichnology refers to advances made between the years 1800 and 1899 in the scientific study of trace fossils, the preserved record of the behavior and physiological processes of ancient life forms, especially fossil footprints. The 19th century was notably the first century in which fossil footprints received scholarly attention. British paleontologist William Buckland performed the first true scientific research on the subject during the early 1830s.

Edward Hitchcock erected the ichnogenus Bifurculapes, meaning "two little forked feet," for trace fossils that were discovered in the Early Jurassic Turners Falls Formation in the Deerfield Basin of Massachusetts. They are insect or crustacean trackways that consist of two rows of two to three tracks per series, with the two larger tracks being oriented parallel or oblique to the trackway axis. The third track, when present, is much smaller than the other two and is oriented approximately perpendicular to the trackway axis. Medial drag marks sometimes are present between the track rows. In trace fossil classification schemes based on behavior, Bifurculapes is considered a repichnion, or locomotion trace. Getty (2020) considered Bifurculapes to represent locomotion under water based on the orientation of some trackways relative to sedimentary structures called current lineations.

This article records new taxa of trace fossils of every kind that are scheduled to be described during the year 2019, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to trace fossil paleontology that are scheduled to occur in the year 2019.

Rhynchosauroides is an ichnogenus, a form taxon based on footprints. The organism producing the footprints was likely a lepidosaur and may have been a sphenodont, an ancestor of the modern tuatara. The footprint consists of five digits, of which the fifth is shortened and the first highly shortened.