Related Research Articles

Antipsychotics, previously known as neuroleptics and major tranquilizers, are a class of psychotropic medication primarily used to manage psychosis, principally in schizophrenia but also in a range of other psychotic disorders. They are also the mainstay, together with mood stabilizers, in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Moreover, they are also used as adjuncts in the treatment of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder.

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by reoccurring episodes of psychosis that are correlated with a general misperception of reality. Other common signs include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking and behavior, social withdrawal, and flat or inappropriate affect. Symptoms develop gradually and typically begin during young adulthood and are never resolved. There is no objective diagnostic test; diagnosis is based on observed behavior, a psychiatric history that includes the person's reported experiences, and reports of others familiar with the person. For a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the described symptoms need to have been present for at least six months or one month. Many people with schizophrenia have other mental disorders, especially substance use disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Schizoaffective disorder is a mental disorder characterized by abnormal thought processes and an unstable mood. This diagnosis requires symptoms of both schizophrenia and a mood disorder: either bipolar disorder or depression. The main criterion is the presence of psychotic symptoms for at least two weeks without any mood symptoms. Schizoaffective disorder can often be misdiagnosed when the correct diagnosis may be psychotic depression, bipolar I disorder, schizophreniform disorder, or schizophrenia. This is a problem as treatment and prognosis differ greatly for most of these diagnoses.

Anhedonia is a diverse array of deficits in hedonic function, including reduced motivation or ability to experience pleasure. While earlier definitions emphasized the inability to experience pleasure, anhedonia is currently used by researchers to refer to reduced motivation, reduced anticipatory pleasure (wanting), reduced consummatory pleasure (liking), and deficits in reinforcement learning. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), anhedonia is a component of depressive disorders, substance-related disorders, psychotic disorders, and personality disorders, where it is defined by either a reduced ability to experience pleasure, or a diminished interest in engaging in previously pleasurable activities. While the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) does not explicitly mention anhedonia, the depressive symptom analogous to anhedonia as described in the DSM-5 is a loss of interest or pleasure.

A thought disorder (TD) is a disturbance in cognition which affects language, thought and communication. Psychiatric and psychological glossaries in 2015 and 2017 identified thought disorders as encompassing poverty of ideas, neologisms, paralogia, word salad, and delusions—all disturbances of thought content and form. Two specific terms have been suggested—content thought disorder (CTD) and formal thought disorder (FTD). CTD has been defined as a thought disturbance characterized by multiple fragmented delusions, and the term thought disorder is often used to refer to an FTD: a disruption of the form of thought. Also known as disorganized thinking, FTD results in disorganized speech and is recognized as a major feature of schizophrenia and other psychoses. Disorganized speech leads to an inference of disorganized thought. Thought disorders include derailment, pressured speech, poverty of speech, tangentiality, verbigeration, and thought blocking. One of the first known cases of thought disorders, or specifically OCD as it is known today, was in 1691. John Moore, who was a bishop, had a speech in front of Queen Mary II, about "religious melancholy."

Schizotypal personality disorder, also known as schizotypal disorder, is a cluster A personality disorder. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) classification describes the disorder specifically as a personality disorder characterized by thought disorder, paranoia, a characteristic form of social anxiety, derealization, transient psychosis, and unconventional beliefs. People with this disorder feel pronounced discomfort in forming and maintaining social connections with other people, primarily due to the belief that other people harbor negative thoughts and views about them. Peculiar speech mannerisms and socially unexpected modes of dress are also characteristic. Schizotypal people may react oddly in conversations, not respond, or talk to themselves. They frequently interpret situations as being strange or having unusual meanings for them; paranormal and superstitious beliefs are common. Schizotypal people usually disagree with the suggestion that their thoughts and behaviors are a 'disorder' and seek medical attention for depression or anxiety instead. Schizotypal personality disorder occurs in approximately 3% of the general population and is more commonly diagnosed in males.

In psychology, schizotypy is a theoretical concept that posits a continuum of personality characteristics and experiences, ranging from normal dissociative, imaginative states to extreme states of mind related to psychosis, especially schizophrenia. The continuum of personality proposed in schizotypy is in contrast to a categorical view of psychosis, wherein psychosis is considered a particular state of mind, which the person either has or does not have.

Expressed emotion (EE), is a measure of the family environment that is based on how the relatives of a psychiatric patient spontaneously talk about the patient. It specifically measures three to five aspects of the family environment: the most important are critical comments, hostility, emotional over-involvement, with positivity and warmth sometimes also included as indications of a low-EE environment. The psychiatric measure of expressed emotion is distinct from the general notion of communicating emotion in interpersonal relationships, and from another psychological metric known as family emotional expressiveness.

Schizophrenia is a neurodevelopmental disorder with no precise or single cause. Schizophrenia is thought to arise from multiple mechanisms and complex gene–environment interactions with vulnerability factors. Risk factors of schizophrenia have been identified and include genetic factors, environmental factors such as experiences in life and exposures in a person's environment, and also the function of a person's brain at it develops. The interactions of these risk factors are intricate, as numerous and diverse medical insults from conception to adulthood can be involved. Many theories have been proposed including the combination of genetic and environmental factors may lead to deficits in the neural circuits that affect sensory input and cognitive functions.

Psychoeducation is an evidence-based therapeutic intervention for patients and their loved ones that provides information and support to better understand and cope with illness. Psychoeducation is most often associated with serious mental illness, including dementia, schizophrenia, clinical depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, bipolar and personality disorders. The term has also been used for programs that address physical illnesses, such as cancer.

The management of schizophrenia usually involves many aspects including psychological, pharmacological, social, educational, and employment-related interventions directed to recovery, and reducing the impact of schizophrenia on quality of life, social functioning, and longevity.

In medicine, a prodrome is an early sign or symptom that often indicates the onset of a disease before more diagnostically specific signs and symptoms develop. More specifically, it refers to the period between the first recognition of a disease's symptom until it reaches its more severe form. It is derived from the Greek word prodromos, meaning "running before". Prodromes may be non-specific symptoms or, in a few instances, may clearly indicate a particular disease, such as the prodromal migraine aura.

Paradoxical laughter is an exaggerated expression of humour which is unwarranted by external events. It may be uncontrollable laughter which may be recognised as inappropriate by the person involved. It is associated with mental illness, such as mania, hypomania or schizophrenia, schizotypal personality disorder and can have other causes. Paradoxical laughter is indicative of an unstable mood, often caused by the pseudobulbar affect, which can quickly change to anger and back again, on minor external cues.

Schizophrenia and tobacco smoking have been historically associated. Smoking is known to harm the health of people with schizophrenia.

The prognosis of schizophrenia is varied at the individual level. In general it has great human and economics costs. It results in a decreased life expectancy of 12–15 years primarily due to its association with obesity, little exercise, and smoking, while an increased rate of suicide plays a lesser role. These differences in life expectancy increased between the 1970s and 1990s, and between the 1990s and 2000s. This difference has not substantially changed in Finland for example – where there is a health system with open access to care.

Schizophrenia is a primary psychotic disorder, whereas, bipolar disorder is a primary mood disorder which can also involve psychosis. Both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are characterized as critical psychiatric disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5). However, because of some similar symptoms, differentiating between the two can sometimes be difficult; indeed, there is an intermediate diagnosis termed schizoaffective disorder.

The epigenetics of schizophrenia is the study of how inherited epigenetic changes are regulated and modified by the environment and external factors and how these changes influence the onset and development of, and vulnerability to, schizophrenia. Epigenetics concerns the heritability of those changes, too. Schizophrenia is a debilitating and often misunderstood disorder that affects up to 1% of the world's population. Although schizophrenia is a heavily studied disorder, it has remained largely impervious to scientific understanding; epigenetics offers a new avenue for research, understanding, and treatment.

Communication deviance (CD) occurs when a speaker fails to effectively communicate and convey meaning to their listeners with confusing speech patterns or illogical patterns. These disturbances can range from vague linguistic references, contradictory statements to more encompassing non-verbal problems at the level of turn-taking.

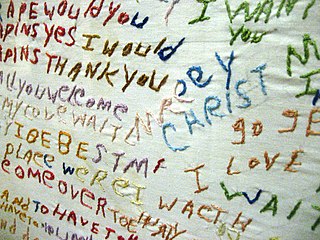

In psychology, graphorrhea, or graphorrhoea, is a communication disorder expressed by excessive wordiness with minor or sometimes incoherent rambling, specifically in written work. Graphorrhea is most commonly associated with schizophrenia but can also result from several psychiatric and neurological disorders such as aphasia, thalamic lesions, temporal lobe epilepsy and mania. Some ramblings may follow some or all grammatical rules but still leave the reader confused and unsure about what the piece is about.

Basic symptoms of schizophrenia are subjective symptoms, described as experienced from a person's perspective, which show evidence of underlying psychopathology. Basic symptoms have generally been applied to the assessment of people who may be at risk to develop psychosis. Though basic symptoms are often disturbing for the person, problems generally do not become evident to others until the person is no longer able to cope with their basic symptoms. Basic symptoms are more specific to identifying people who exhibit signs of prodromal psychosis (prodrome) and are more likely to develop schizophrenia over other disorders related to psychosis. Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder, but is not synonymous with psychosis. In the prodrome to psychosis, uncharacteristic basic symptoms develop first, followed by more characteristic basic symptoms and brief and self-limited psychotic-like symptoms, and finally the onset of psychosis. People who were assessed to be high risk according to the basic symptoms criteria have a 48.5% likelihood of progressing to psychosis. In 2015, the European Psychiatric Association issued guidance recommending the use of a subscale of basic symptoms, called the Cognitive Disturbances scale (COGDIS), in the assessment of psychosis risk in help-seeking psychiatric patients; in a meta-analysis, COGDIS was shown to be as predictive of transition to psychosis as the Ultra High Risk (UHR) criteria up to 2 years after assessment, and significantly more predictive thereafter. The basic symptoms measured by COGDIS, as well as those measured by another subscale, the Cognitive-Perceptive basic symptoms scale (COPER), are predictive of transition to schizophrenia.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Padma, T. V. (2014). "Developing countries: The outcomes paradox". Nature. 508 (7494): S14–S15. Bibcode:2014Natur.508S..14P. doi: 10.1038/508S14a . PMID 24695329. S2CID 4463164.

- ↑ Cohen, A.; Patel, V.; Thara, R.; Gureje, O. (9 April 2007). "Questioning an Axiom: Better Prognosis for Schizophrenia in the Developing World?". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 34 (2): 229–244. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm105. PMC 2632419 . PMID 17905787.

- ↑ Sartorius, N.; Gulbinat, W.; Harrison, G.; Laska, E.; Siegel, C. (September 1996). "Long-term follow-up of schizophrenia in 16 countries: A description of the international study of schizophrenia conducted by the World Health Organization". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 31 (5): 249–258. doi:10.1007/BF00787917. PMID 8909114. S2CID 22846998.

- ↑ Patel, KR; Cherian, J; Gohil, K; Atkinson, D (September 2014). "Schizophrenia: overview and treatment options". P & T: A Peer-Reviewed Journal for Formulary Management. 39 (9): 638–45. PMC 4159061 . PMID 25210417.

- ↑ "Diagnosis - Schizophrenia". nhs.uk. 12 February 2021.

- ↑ "Schizophrenia". www.nhsinform.scot.

- ↑ Naheed, Mahmuda; Akter, Khondoker Ayesha; Tabassum, Fatema; Mawla, Rumana; Rahman, Mahmudur (1970-01-01). "Factors contributing the outcome of Schizophrenia in developing and developed countries: A brief review". International Current Pharmaceutical Journal. 1 (4): 81–85. doi: 10.3329/icpj.v1i4.10063 . ISSN 2224-9486.

- ↑ Chabukswar. "Notes in Tune: Arts-based Therapy (ABT) at Schizophrenia Awareness Association in Pune, India". www.psychosocial.com. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- 1 2 Cain, M. (1982). "Perspectives on Family and Fertility in Developing Countries". Population Studies. 36 (2): 159–175. doi:10.2307/2174195. ISSN 0032-4728. JSTOR 2174195. PMID 22077270.

- ↑ Leh, Keh-Ming; Kleinman, Arthur (1988). "Psychopathology and Clinical Course of Schizophrenia: A Cross-Cultural Perspective". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 14 (4): 555–567. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.4.555 . PMID 3064282.

- 1 2 Amaresha, Anekal C.; Venkatasubramanian, Ganesan (January 2012). "Expressed Emotion in Schizophrenia: An Overview". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 34 (1): 12–20. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.96149 . PMC 3361836 . PMID 22661801.

- ↑ Ng, Siu-Man; Fung, Melody Hiu-Ying; Gao, Siyu (November 2020). "High level of expressed emotions in the family of people with schizophrenia: has a covert abrasive behaviours component been overlooked?". Heliyon. 6 (11): e05441. Bibcode:2020Heliy...605441N. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05441 . PMC 7658711 . PMID 33210009. S2CID 226976334.

- ↑ Pitschel-Walz, G.; Leucht, S.; Bauml, J.; Kissling, W.; Engel, R. R. (1 January 2001). "The Effect of Family Interventions on Relapse and Rehospitalization in Schizophrenia--A Meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 27 (1): 73–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006861 . PMID 11215551.

- ↑ "Why Do the Poor Have Large Families?". Compassion Australia.

- ↑ Koschorke, Mirja; Padmavati, R.; Kumar, Shuba; Cohen, Alex; Weiss, Helen A.; Chatterjee, Sudipto; Pereira, Jesina; Naik, Smita; John, Sujit; Dabholkar, Hamid; Balaji, Madhumitha; Chavan, Animish; Varghese, Mathew; Thara, R.; Thornicroft, Graham; Patel, Vikram (1 December 2014). "Experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in India". Social Science & Medicine. 123: 149–159. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.035. ISSN 0277-9536. PMC 4259492 . PMID 25462616.

- ↑ Bangalore, NG; Varambally, S (July 2012). "Yoga therapy for Schizophrenia". International Journal of Yoga. 5 (2): 85–91. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.98212 . PMC 3410202 . PMID 22869990.

- ↑ Kulhara, Parmanand; Shah, Ruchita; Grover, Sandeep (2009-06-01). "Is the course and outcome of schizophrenia better in the 'developing' world?". Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2 (2): 55–62. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2009.04.003. ISSN 1876-2018. PMID 23051029.