History

Some country fans consider outlaw country a slightly harder-edged variant of progressive country. [6] The outlaw sound has its roots in blues music, [7] honky tonk music of the 1940s and 1950s, rockabilly of the 1950s, and the evolving genre of rock and roll. [4] [8] Early outlaws were particularly influenced by predecessors like Bob Wills, Hank Williams, Elvis Presley, and Buddy Holly. However, an even greater transition occurred after Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson were able to secure their own recording rights, and began the trend of bucking the "Nashville sound". According to Michael Streissguth, author of Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, Jennings and Nelson became outlaws when they "won the right" to record with the producers and studio musicians they preferred. [4]

The 1960s was a decade of enormous change, a change reflected in the music of the time. The Beatles, Brian Wilson, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, and many who followed in their wake cast off the traditional role of the recording artist. They wrote their own material, had creative input in their albums, and refused to conform to what society required of its youth. One author states that the Beatnik movement, from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, was a precursor to outlaw country, as participants in both movements emphasized that they felt "out of place" in mainstream society. [9]

At the same time, country music was declining into a formulaic genre that appeared to offer the establishment what it wanted with artists such as Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton making the kind of music that was anathema to the growing counterculture. While Nashville continued to be the focus of mainstream country music, cities like Lubbock and Austin became the creative centers of outlaw country. Southern rock also had a strong influence on the outlaw country movement, and that sound and style of recording was centered in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. In the Western United States, the Bakersfield sound was providing a counterpoint to the traditional Nashville sound, and the counterculture was also giving rise to the fusion genre of country rock, with groups such as the Flying Burrito Brothers and The First National Band (whose lead singer Michael Nesmith had similar creative rebellion against the West Coast music establishment dating to his time with The Monkees).

Origin of term

The movement was named, at various points, "redneck rock", progressive country, or "armadillo country", after the animal which would become the movement's unofficial mascot, before it was termed "outlaw country". [1] The origin of the outlaw label is debated. According to Jason Mellard, author of Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texan in Popular Culture, the term "seems to have sedimented over time rather than exploding in the national consciousness all at once". [10]

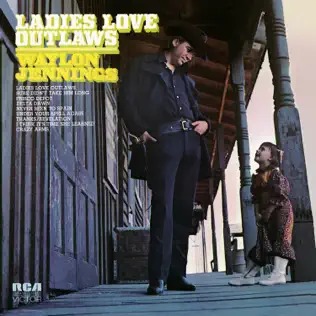

The term is often attributed to "Ladies Love Outlaws", a song by Lee Clayton and sung by Waylon Jennings on the 1972 album of the same name. [11] Another plausible explanation is the use of the term a year later by publicist Hazel Smith of Glaser Studios to describe the music of Jennings and Tompall Glaser. Art critic Dave Hickey, who wrote a 1974 profile in Country Music magazine, also used the term to describe artists who opposed the commercial control of the Nashville recording industry. [10]

In 1976, the Outlaw movement solidified the term with the release of Wanted! The Outlaws , a compilation album featuring songs sung by Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser. Wanted! The Outlaws became the first country album to be platinum-certified, reaching sales of one million. [12]

Development

As Southern rock flourished, veteran country artists incorporated rock into their music in this genre. Songwriters/guitarists such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Hank Williams, Jr. shed the formulaic Nashville sound, grew long hair, and replaced rhinestone-studded suits with leather jackets. Outlaw country artists spoke openly about smoking marijuana. [13] Fiercely independent, the "outlaws" abandoned lush orchestrations, stripped the music to its country core, and added a rock sensibility to the sound. [2] At the same time, outlaw country performers brought back older styles that had fallen into disuse, such as honky tonk songs and "cowboy ballads". [14] As well, Nelson and Jennings incorporated more R&B and soul music into their country music by working with Memphis and Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section musicians. [13]

The outlaw country artists aimed to resist the big "machine" of the Nashville establishment, which "codified" norms of sounds, styles, and even appearance and behavior through influential "tastemaker" shows such as Grand Ole Opry. [15] The Grand Ole Opry, which was "staunchly conservative", used its influence over Nashville's Music Row to control who could play and what types of songs they could perform. Jennings described his experience in that city's recording industry as like working on an assembly line, in which records were produced like "clockwork". [15]

In 1973 Jennings produced Lonesome, On'ry and Mean . The theme song was written by Steve Young, a songwriter and performer who never made it in the mainstream, but whose songs helped to create the outlaw style.[ citation needed ] The follow-up album for Jennings was Honky Tonk Heroes and the songwriter hero was Texan Billy Joe Shaver. Like Steve Young, Shaver never made it big, but his 1973 album Old Five and Dimers Like Me is considered a country classic in the outlaw genre.[ citation needed ]

Willie Nelson's career as a songwriter in Nashville peaked in the late 1960s. As a songwriter, he had written a number of major pop-crossover hits, including "Crazy" for Patsy Cline and "Hello Walls" for Faron Young, but as a singer, he was getting nowhere. He left Nashville in 1971 to return to Texas. The musicians he met in Austin had been developing the folk and rock influenced country music that grew into the outlaw genre. Performing and associating with the likes of Jerry Jeff Walker, Michael Martin Murphey and Billy Joe Shaver helped shape his future career.

Williams Jr. had long spent much of his early career in the shadow of his father Hank Williams Sr., who died when Williams Jr. was three years old. In 1975, Williams was severely injured in an avalanche while mountain climbing, disfiguring him to the point where he no longer resembled his father; he grew a beard to hide the scars, which he has maintained ever since. He also began collaborating with the other outlaws, beginning with his album Hank Williams Jr. and Friends released shortly before he was injured.

At the same time as Nelson was reinventing himself, other influential musicians were writing songs and playing in Austin and Lubbock. Butch Hancock, Joe Ely and Jimmie Dale Gilmore formed the Flatlanders, a group that never sold huge numbers of albums, but continues to perform. The three founders have each made a significant contribution to the development of the outlaw genre. The Lost Gonzo Band and their work in conjunction with Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Murphey were integral in the birth of Outlaw Country. [16]

Other Texans, like Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle and Guy Clark, developed the outlaw ethos through their songwriting and ways of living.

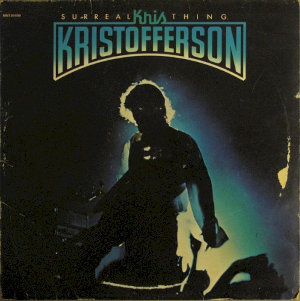

Although Johnny Cash spent most of his time in Arkansas and Tennessee, he experienced a revival of his career with the outlaw movement, especially after his live albums At Folsom Prison and At San Quentin , both of which were recorded in prisons. Cash had working relationships with Nelson, Jennings and Kris Kristofferson in his later career, culminating in the formation of The Highwaymen; the four would record and perform as a supergroup in addition to their solo careers through the late 1990s. Cash had also been on good terms with several folk counterculture figures, a fact that irked Nashville and television executives (Cash hosted a variety show from 1969 to 1971). Like the other outlaw singers, he eschewed the polished Nashville look with a somewhat ragged (especially in later years), all-black outfit that inspired Cash's nickname, the "Man in Black".

Decline of the movement

The outlaw movement's heyday was in the mid- to late 1970s; although the core artists of the movement continued to record for many years afterward (Nelson, in particular, was recording hits well into the following decade while Hank Williams, Jr. achieved his greatest success during the 1980s), the outlaw movement as a fad was already declining by 1978. By 1980 mainstream country music was practically dominated by country pop artists and crossover acts. The movement was furthermore falling victim to the same pigeonholing and commercialization as mainstream country music; Mickey Newbury, a prominent influence on many outlaw artists, rejected the "outlaw" label, stating "I quit playing cowboys when I grew up." [17] Williams also noted in his song "All My Rowdy Friends (Have Settled Down)" that many of the core "outlaws" were growing up and abandoning the drugs and hard partying that had driven much of their lives in the 1970s in favor of their home lives and other pursuits. Jennings had a hit song with "Don't You Think This Outlaw Bit's Done Got Out of Hand" in 1978, which likewise attributed the decline to pressures from drug use. Some of the outlaws would have a slight career renaissance in the mid-1980s with the neotraditional country revival, which revived the older styles of both mainstream and "outlaw" country music of years past.