A migrant worker is a person who migrates within a home country or outside it to pursue work. Migrant workers usually do not have an intention to stay permanently in the country or region in which they work.

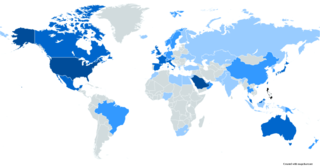

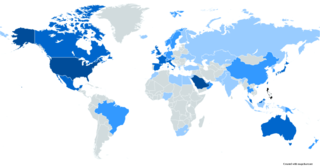

An Overseas Filipino is a person of full or partial Filipino origin who trace their ancestry back to the Philippines but are living and working outside of the country. They get jobs in countries and they move to live in countries that they get jobs in. This term generally applies to both people of Filipino ancestry and citizens abroad. As of 2019, there were over 12 million Filipinos overseas.

The Department of Foreign Affairs is the executive department of the Philippine government tasked to contribute to the enhancement of national security, protection of the territorial integrity and national sovereignty, to participate in the national endeavor of sustaining development and enhancing the Philippines' competitive edge, to protect the rights and promote the welfare of Filipinos overseas and to mobilize them as partners in national development, to project a positive image of the Philippines, and to increase international understanding of Philippine culture for mutually-beneficial relations with other countries.

Filipinos in Kuwait are either migrants from or descendants of the Philippines living in Kuwait. As of 2020, there are roughly 241,000 of these Filipinos in Kuwait. Most people in the Filipino community are migrant workers, and approximately 60% of Filipinos in Kuwait are employed as domestic workers.

The labor migration policy of the Philippine government allows and encourages emigration. The Department of Foreign Affairs, which is one of the government's arms of emigration, grants Filipinos passports that allow entry to foreign countries. In 1952, the Philippine government formed the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) as the agency responsible for opening the benefits of the overseas employment program. In 1995, it enacted the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipino Act in order to "institute the policies of overseas employment and establish a higher standard of protection and promotion of the welfare of migrant workers and their families and overseas Filipinos in distress." In 2022, the Department of Migrant Workers was formed, incorporating the POEA with its functions and mandate becoming the backbone of the new executive department.

Filipino seamen, also referred to as Filipino seafarers or Filipino sailors, are seamen, sailors, or seafarers from the Philippines. Although, in general, the term "Filipino seamen" may include personnel from the Philippine Navy or the Philippine Marine Corps, it specifically refers to overseas Filipinos who are "sea-based migrant Filipino workers".

The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration was an agency of the government of the Philippines responsible for opening the benefits of the overseas employment program of the Philippines. It is the main government agency assigned to monitor and supervise overseas recruitment and manning agencies in the Philippines. The POEA's office is located at EDSA corner Ortigas Avenue, Mandaluyong, Philippines.

Filipinos in Taiwan consist mainly of immigrants and workers from the Philippines. Filipinos form the third largest national contingent of migrant workers and account for about one-fifth of foreign workers in Taiwan as of April 2019.

The Labor policy in the Philippines is specified mainly by the country's Labor Code of the Philippines and through other labor laws. They cover 38 million Filipinos who belong to the labor force and to some extent, as well as overseas workers. They aim to address Filipino workers’ legal rights and their limitations with regard to the hiring process, working conditions, benefits, policymaking on labor within the company, activities, and relations with employees.

Filipinos in Oman are either migrants or descendants of the Philippines living in Oman. As of 2011, there are between 40,000 and 46,000 of these Filipinos in Oman. A large destination for Overseas Filipino workers (OFWs), Oman was the only Middle Eastern nation included on the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration's list of nations safe for OFWs. The country still holds the title up to this day.

Philippines–South Sudan relations refers to the bilateral relationship between the Philippines and South Sudan. The Philippines recognized South Sudan as a sovereign state nearly a month after it declared its independence on 9 July 2011. The Philippine embassy in Nairobi has jurisdiction over South Sudan since March 2013. This was held previously by Philippine embassy in Cairo.

MariaSusana "Toots" Vasquez Ople was a Filipina politician and Overseas Filipino Workers' (OFW) rights advocate who served as the first Secretary of the Department of Migrant Workers.

The Overseas Workers Welfare Administration is an attached agency of the Department of Migrant Workers of the Philippines. It protects the interests of Overseas Filipino Workers and their families, providing social security, cultural services and help with employment, remittances and legal matters. It is funded by an obligatory annual contribution from overseas workers and their employers. The agency was founded in 1977 as the Welfare and Training Fund for Overseas Workers. Its head office is at F.B. Harrison Street corner 7th Street in Pasay, near EDSA Extension, Philippines.

In early 2018, Kuwait and the Philippines were embroiled in a diplomatic crisis over the situation of Filipino migrant workers in the gulf country.

Overseas Filipinos, including Filipino migrant workers outside the Philippines, have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As of June 1, 2021, there have been 19,765 confirmed COVID-19 cases of Filipino citizens residing outside the Philippines with 12,037 recoveries and 1,194 deaths. The official count from the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) on the cases of overseas Filipinos is not included in the national tally of the Philippine government. Repatriates on the other hand are included in the national tally of the Department of Health (DOH) but are listed separately from regional counts.

The Department of Migrant Workers is the executive department of the Philippine government responsible for the protection of the rights and promote the welfare of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) and their families. The department was created under the Department of Migrant Workers Act that was signed by President Rodrigo Duterte on December 30, 2021. The functions and mandate of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) will serve as the backbone of the department and absorbing the seven offices of the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) and Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) namely the Office of the Undersecretary for Migrant Workers' Affairs (OUMWA) of the DFA, Philippine Overseas Labor Office (POLO), International Labor Affairs Bureau (ILAB), National Reintegration Center for OFWs (NRCO) and the National Maritime Polytechnic (NMP) of the DOLE. The Overseas Workers Welfare Administration will serve as its attached agency and the DMW secretary will serve as the concurrent chairperson of OWWA.

Abdullah Derupong Mama-o is a Filipino government official who served as the ad interim Secretary of the Department of Migrant Workers under the Duterte administration.

Jullebee Cabilis Ranara was an Overseas Filipino Worker who was found dead in the desert on January 21, 2023, in Kuwait. She was reportedly raped, murdered, burnt and thrown in the desert. The death revived public discourse on the plight of Filipino migrant workers living in Kuwait.

An Overseas Employment Certificate (OEC), also known as an exit pass or an exit clearance, is an identity document for Filipino migrant workers or Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) departing from the Philippines.