Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337. He was the first emperor to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterranea, he was the son of Flavius Constantius, a Roman army officer of Illyrian origin who had been one of the four rulers of the Tetrarchy. His mother, Helena, was a Greek woman of low birth and a Christian. Later canonized as a saint, she is traditionally attributed with the conversion of her son. Constantine served with distinction under the Roman emperors Diocletian and Galerius. He began his career by campaigning in the eastern provinces before being recalled in the west to fight alongside his father in the province of Britannia. After his father's death in 306, Constantine was acclaimed as augustus (emperor) by his army at Eboracum. He eventually emerged victorious in the civil wars against emperors Maxentius and Licinius to become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire by 324.

Diocletian, nicknamed "Jovius", was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Diocles to a family of low status in the Roman province of Dalmatia. Diocles rose through the ranks of the military early in his career, eventually becoming a cavalry commander for the army of Emperor Carus. After the deaths of Carus and his son Numerian on a campaign in Persia, Diocles was proclaimed emperor by the troops, taking the name Diocletianus. The title was also claimed by Carus's surviving son, Carinus, but Diocletian defeated him in the Battle of the Margus.

Galerius Valerius Maximianus was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the Danube against the Carpi, defeating them in 297 and 300. Although he was a staunch opponent of Christianity, Galerius ended the Diocletianic Persecution when he issued an Edict of Toleration in Serdica in 311.

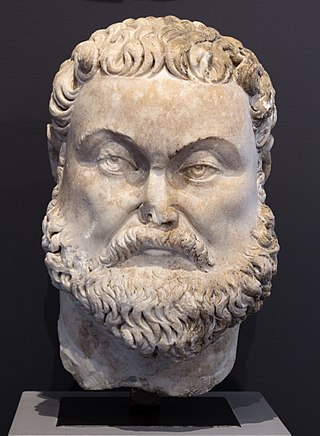

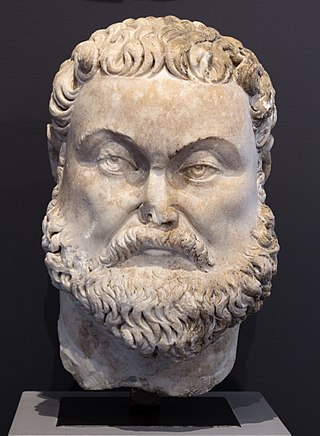

Maximian, nicknamed Herculius, was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was Caesar from 285 to 286, then Augustus from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his co-emperor and superior, Diocletian, whose political brain complemented Maximian's military brawn. Maximian established his residence at Trier but spent most of his time on campaign. In late 285, he suppressed rebels in Gaul known as the Bagaudae. From 285 to 288, he fought against Germanic tribes along the Rhine frontier. Together with Diocletian, he launched a scorched earth campaign deep into Alamannic territory in 288, refortifying the frontier.

Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Carausius was a military commander of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. He was a Menapian from Belgic Gaul, who usurped power in 286, during the Carausian Revolt, declaring himself emperor in Britain and northern Gaul. He did this only 13 years after the Gallic Empire of the Batavian Postumus was ended in 273. He held power for seven years, fashioning the name "Emperor of the North" for himself, before being assassinated by his finance minister Allectus.

Flavius Julius Crispus was the eldest son of the Roman emperor Constantine I, as well as his junior colleague (caesar) from March 317 until his execution by his father in 326. The grandson of the augustus Constantius I, Crispus was the elder half-brother of the future augustus Constantine II and became co-caesar with him and with his cousin Licinius II at Serdica, part of the settlement ending the Cibalensean War between Constantine and his father's rival Licinius I. Crispus ruled from Augusta Treverorum (Trier) in Roman Gaul between 318 and 323 and defeated the navy of Licinius I at the Battle of the Hellespont in 324, which with the land Battle of Chrysopolis won by Constantine forced the resignation of Licinius and his son, leaving Constantine the sole augustus and the Constantinian dynasty in control of the entire empire. It is unclear what the legal status of the relationship Crispus's mother Minervina had with Constantine was; Crispus may have been an illegitimate son.

Latinius Pacatus Drepanius, one of the Latin panegyrists, flourished at the end of the 4th century AD.

Eumenius, was one of the Ancient Roman panegyrists and author of a speech transmitted in the collection of the Panegyrici Latini.

Claudius Mamertinus was an official in the Roman Empire. In late 361 he took part in the Chalcedon tribunal to condemn the ministers of Constantius II, and in 362, he was made consul as a reward by the new Emperor Julian; on January 1 of that year he delivered a panegyric in Constantinople by way of thanks to the Emperor. The text of this is extant, preserved in the Panegyrici Latini. Claudius Mamertinus later went on to become praetorian prefect of Italy, Africa, and Illyria before being removed from public office in 368 for embezzlement.

Nazarius,, was a Roman and a Latin rhetorician and panegyrist. He was, according to Ausonius, a professor of rhetoric at Burdigala (Bordeaux).

The Carausian revolt (AD 286–296) was an episode in Roman history during which a Roman naval commander, Carausius, declared himself emperor over Britain and northern Gaul. His Gallic territories were retaken by the western Caesar Constantius Chlorus in 293, after which Carausius was assassinated by his subordinate Allectus. Britain was regained by Constantius and his subordinate Asclepiodotus in 296.

The Thervingi, Tervingi, or Teruingi were a Gothic people of the plains north of the Lower Danube and west of the Dniester River in the 3rd and the 4th centuries.

Merogais was an early Frankish king, who, along with his co-ruler Ascaric, is the earliest Frankish ruler known. He was an enemy of the Roman Empire. Merogais is mentioned in the Panegyrici latini and by Eutropius and Eumenius. The very existence of Merogais depends on the manuscript reading of Johann Kaspar Zeuss. The sentence which names the two kings begins with Asacari or Assaccari in all manuscripts, but it ends with the corrupt forms cinere gaisique, cumero geasique, cymero craisique, and cymero caisique. Zeuss reads those sentences as ending respectively cum Neregaisique, cum Merogeasique, cum Merocraisique, and cum Merocaisique, each meaning as "and with Merogais".

Ascaric or Ascarich was an early Frankish war leader, who, along with his co-leader, Merogais, are the earliest known leaders explicitly called Frankish, although the name of the Franks is earlier.

The civil wars of the Tetrarchy were a series of conflicts between the co-emperors of the Roman Empire, starting from 306 AD with the usurpation of Maxentius and the defeat of Severus to the defeat of Licinius at the hands of Constantine I in 324 AD.

The German and Sarmatian campaigns of Constantine were fought by the Roman Emperor Constantine I against the neighbouring Germanic peoples, including the Franks, Alemanni and Goths, as well as the Sarmatian Iazyges, along the whole Roman northern defensive system to protect the empire's borders, between 306 and 336.

Brian Herbert Warmington (1924–2013) was a British classicist and ancient historian.

In Byzantine rhetoric, a basilikos logos or logos eis ton autokratora is an encomium addressed to an emperor on an important occasion, regularly at Epiphany.

The Battle of Brescia was a confrontation that took place during the summer of 312, between the Roman emperors Constantine the Great and Maxentius in the town of Brescia, in northern Italy. Maxentius declared war on Constantine on the grounds that he wanted to avenge the death of his father Maximian, who had committed suicide after being defeated by him. Constantine would respond with a massive invasion of Italy.

The siege of Segusio or siege of Susa was the first clash of the civil war between the Roman emperors Constantine the Great and Maxentius in the spring of 312. In that year, Maxentius had declared war on Constantine, claiming to intend to avenge the death of his father Maximian, who had committed suicide after being defeated by him. Constantine would respond with an invasion of northern Italy.