Related Research Articles

In aphasia, a person may be unable to comprehend or unable to formulate language because of damage to specific brain regions. The major causes are stroke and head trauma; prevalence is hard to determine but aphasia due to stroke is estimated to be 0.1–0.4% in the Global North. Aphasia can also be the result of brain tumors, epilepsy, autoimmune neurological diseases, brain infections, or neurodegenerative diseases.

Expressive aphasia, also known as Broca's aphasia, is a type of aphasia characterized by partial loss of the ability to produce language, although comprehension generally remains intact. A person with expressive aphasia will exhibit effortful speech. Speech generally includes important content words but leaves out function words that have more grammatical significance than physical meaning, such as prepositions and articles. This is known as "telegraphic speech". The person's intended message may still be understood, but their sentence will not be grammatically correct. In very severe forms of expressive aphasia, a person may only speak using single word utterances. Typically, comprehension is mildly to moderately impaired in expressive aphasia due to difficulty understanding complex grammar.

In neuroscience and psychology, the term language center refers collectively to the areas of the brain which serve a particular function for speech processing and production. Language is a core system that gives humans the capacity to solve difficult problems and provides them with a unique type of social interaction. Language allows individuals to attribute symbols to specific concepts, and utilize them through sentences and phrases that follow proper grammatical rules. Finally, speech is the mechanism by which language is orally expressed.

Wernicke's aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia, sensory aphasia, fluent aphasia, or posterior aphasia, is a type of aphasia in which individuals have difficulty understanding written and spoken language. Patients with Wernicke's aphasia demonstrate fluent speech, which is characterized by typical speech rate, intact syntactic abilities and effortless speech output. Writing often reflects speech in that it tends to lack content or meaning. In most cases, motor deficits do not occur in individuals with Wernicke's aphasia. Therefore, they may produce a large amount of speech without much meaning. Individuals with Wernicke's aphasia are typically unaware of their errors in speech and do not realize their speech may lack meaning. They typically remain unaware of even their most profound language deficits.

Broca's area, or the Broca area, is a region in the frontal lobe of the dominant hemisphere, usually the left, of the brain with functions linked to speech production.

A communication disorder is any disorder that affects an individual's ability to comprehend, detect, or apply language and speech to engage in dialogue effectively with others. This also encompasses deficiencies in verbal and non-verbal communication styles. The delays and disorders can range from simple sound substitution to the inability to understand or use one's native language. This article covers subjects such as diagnosis, the DSM-IV, the DSM-V, and examples like sensory impairments, aphasia, learning disabilities, and speech disorders.

Aphasiology is the study of language impairment usually resulting from brain damage, due to neurovascular accident—hemorrhage, stroke—or associated with a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, including different types of dementia. These specific language deficits, termed aphasias, may be defined as impairments of language production or comprehension that cannot be attributed to trivial causes such as deafness or oral paralysis. A number of aphasias have been described, but two are best known: expressive aphasia and receptive aphasia.

Agraphia is an acquired neurological disorder causing a loss in the ability to communicate through writing, either due to some form of motor dysfunction or an inability to spell. The loss of writing ability may present with other language or neurological disorders; disorders appearing commonly with agraphia are alexia, aphasia, dysarthria, agnosia, acalculia and apraxia. The study of individuals with agraphia may provide more information about the pathways involved in writing, both language related and motoric. Agraphia cannot be directly treated, but individuals can learn techniques to help regain and rehabilitate some of their previous writing abilities. These techniques differ depending on the type of agraphia.

Anomic aphasia is a mild, fluent type of aphasia where individuals have word retrieval failures and cannot express the words they want to say. By contrast, anomia is a deficit of expressive language, and a symptom of all forms of aphasia, but patients whose primary deficit is word retrieval are diagnosed with anomic aphasia. Individuals with aphasia who display anomia can often describe an object in detail and maybe even use hand gestures to demonstrate how the object is used, but cannot find the appropriate word to name the object. Patients with anomic aphasia have relatively preserved speech fluency, repetition, comprehension, and grammatical speech.

Wernicke's area, also called Wernicke's speech area, is one of the two parts of the cerebral cortex that are linked to speech, the other being Broca's area. It is involved in the comprehension of written and spoken language, in contrast to Broca's area, which is primarily involved in the production of language. It is traditionally thought to reside in Brodmann area 22, which is located in the superior temporal gyrus in the dominant cerebral hemisphere, which is the left hemisphere in about 95% of right-handed individuals and 70% of left-handed individuals.

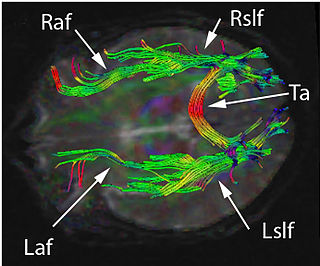

Conduction aphasia, also called associative aphasia, is an uncommon form of difficulty in speaking (aphasia). It is caused by damage to the parietal lobe of the brain. An acquired language disorder, it is characterised by intact auditory comprehension, coherent speech production, but poor speech repetition. Affected people are fully capable of understanding what they are hearing, but fail to encode phonological information for production. This deficit is load-sensitive as the person shows significant difficulty repeating phrases, particularly as the phrases increase in length and complexity and as they stumble over words they are attempting to pronounce. People have frequent errors during spontaneous speech, such as substituting or transposing sounds. They are also aware of their errors and will show significant difficulty correcting them.

Global aphasia is a severe form of nonfluent aphasia, caused by damage to the left side of the brain, that affects receptive and expressive language skills as well as auditory and visual comprehension. Acquired impairments of communicative abilities are present across all language modalities, impacting language production, comprehension, and repetition. Patients with global aphasia may be able to verbalize a few short utterances and use non-word neologisms, but their overall production ability is limited. Their ability to repeat words, utterances, or phrases is also affected. Due to the preservation of the right hemisphere, an individual with global aphasia may still be able to express themselves through facial expressions, gestures, and intonation. This type of aphasia often results from a large lesion of the left perisylvian cortex. The lesion is caused by an occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery and is associated with damage to Broca's area, Wernicke's area, and insular regions which are associated with aspects of language.

Transcortical sensory aphasia (TSA) is a kind of aphasia that involves damage to specific areas of the temporal lobe of the brain, resulting in symptoms such as poor auditory comprehension, relatively intact repetition, and fluent speech with semantic paraphasias present. TSA is a fluent aphasia similar to Wernicke's aphasia, with the exception of a strong ability to repeat words and phrases. The person may repeat questions rather than answer them ("echolalia").

In psycholinguistics, language processing refers to the way humans use words to communicate ideas and feelings, and how such communications are processed and understood. Language processing is considered to be a uniquely human ability that is not produced with the same grammatical understanding or systematicity in even human's closest primate relatives.

Transcortical motor aphasia (TMoA), also known as commissural dysphasia or white matter dysphasia, results from damage in the anterior superior frontal lobe of the language-dominant hemisphere. This damage is typically due to cerebrovascular accident (CVA). TMoA is generally characterized by reduced speech output, which is a result of dysfunction of the affected region of the brain. The left hemisphere is usually responsible for performing language functions, although left-handed individuals have been shown to perform language functions using either their left or right hemisphere depending on the individual. The anterior frontal lobes of the language-dominant hemisphere are essential for initiating and maintaining speech. Because of this, individuals with TMoA often present with difficulty in speech maintenance and initiation.

Mixed transcortical aphasia is the least common of the three transcortical aphasias. This type of aphasia can also be referred to as "Isolation Aphasia". This type of aphasia is a result of damage that isolates the language areas from other brain regions. Broca's, Wernicke's, and the arcuate fasiculus are left intact; however, they are isolated from other brain regions.

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words, and using those words in their semantic character as words in the lexicon of a language according to the syntactic constraints that govern lexical words' function in a sentence. In speaking, speakers perform many different intentional speech acts, e.g., informing, declaring, asking, persuading, directing, and can use enunciation, intonation, degrees of loudness, tempo, and other non-representational or paralinguistic aspects of vocalization to convey meaning. In their speech, speakers also unintentionally communicate many aspects of their social position such as sex, age, place of origin, physical states, psychological states, physico-psychological states, education or experience, and the like.

Auditory agnosia is a form of agnosia that manifests itself primarily in the inability to recognize or differentiate between sounds. It is not a defect of the ear or "hearing", but rather a neurological inability of the brain to process sound meaning. While auditory agnosia impairs the understanding of sounds, other abilities such as reading, writing, and speaking are not hindered. It is caused by bilateral damage to the anterior superior temporal gyrus, which is part of the auditory pathway responsible for sound recognition, the auditory "what" pathway.

Jargon aphasia is a type of fluent aphasia in which an individual's speech is incomprehensible, but appears to make sense to the individual. Persons experiencing this condition will either replace a desired word with another that sounds or looks like the original one, or has some other connection to it, or they will replace it with random sounds. Accordingly, persons with jargon aphasia often use neologisms, and may perseverate if they try to replace the words they can not find with sounds.

Music therapy for non-fluent aphasia is a method for treating patients who have lost the ability to speak after a stroke or accident. Non-fluent aphasia, also called expressive aphasia, is a neurological disorder that deprives patients of the ability to express language. It is usually caused by stroke or lesions in Broca's area, which is a language-dominant area that is responsible for speech production located in the left hemisphere of the brain. However, when lesions form in Broca's area this only affects patients’ speech ability, while their ability to sing remains unaffected. Since several studies have shown that right hemispheric regions are more active during singing, music therapy involving melodic elements is deemed to be a potential treatment for non-fluent aphasia, as singing might activate patients’ right hemisphere to compensate with their lesioned left hemisphere. Aside from singing, many other music therapy techniques have also been attempted such as rhythms and poetic emphasis, this may add to the effectiveness of some techniques is also shown. Although there are many possible explanations for the mechanism of music therapy, the underlying mechanism remains unclear, as some studies indicate contradictory results.

References

- 1 2 Manasco, Hunter (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. p. 73.

- 1 2 Biran M, Friedmann N (2005). "From phonological paraphasias to the structure of the phonological output lexicon". Language and Cognitive Processes. 20 (4): 589–616. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.69.7795 . doi:10.1080/01690960400005813. S2CID 14484194.

- ↑ Julius Althaus (1877). Diseases of the nervous system: their prevalence and pathology. Smith, Elder. p. 163.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sinanovic O, Mrkonjic Z, Zukic S, Vidovic M, Imamovic K. 2011. Post-stroke language disorders. Acta clinica Croatica 50:79-94

- 1 2 3 Kreisler A, Godefroy O, Delmaire C, Debachy B, Leclercq M, et al. (2000). "The anatomy of aphasia revisited". Neurology. 54 (5): 1117–23. doi:10.1212/wnl.54.5.1117. PMID 10720284. S2CID 21847976.

- ↑ Rohrer JD, Knight WD, Warren JE, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD (2008). "Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias". Brain. 131 (Pt 1): 8–38. doi:10.1093/brain/awm251. PMC 2373641 . PMID 17947337.

- ↑ Gallaher, Alan J. (Jun 24, 1981). "Syntactic versus semantic performances of agrammatic Broca's aphasics on tests of constituent-element-ordering". Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 24 (2): 217–218. doi:10.1044/jshr.2402.217. PMID 7265937.

- ↑ Kellogg, Margaret Kimberly (2012). "Conceptual mechanisms underlying noun and verb categorization: Evidence from paraphasia". Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 20 (1).

- ↑ Huber, Mary (1944). "A Phonetic Approach to the Problem of Perception in a Case of Wernicke's Aphasia". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: 227–238.

- 1 2 Berg T (2006). "A structural account of phonological paraphasias". Brain and Language. 96 (3): 331–56. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2006.01.005. PMID 16615177.

- ↑ Buckingham HW (1986). "The scan-copier mechanism and the positional level of language production: Evidence from phonemic paraphasia". Cognitive Science. 10 (2): 195–217. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog1002_4 .

- 1 2 3 Corina DP, Loudermilk BC, Detwiler L, Martin RF, Brinkley JF, Ojemann G (2010). "Analysis of naming errors during cortical stimulation mapping: Implications for models of language representation". Brain and Language. 115 (2): 101–12. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2010.04.001. PMC 3247200 . PMID 20452661.

- ↑ Caplan D, Kellar L, Locke S (1972). "Inflection of neologisms in aphasia". Brain. 95 (1): 169–72. doi: 10.1093/brain/95.1.169 . PMID 5023086.

- 1 2 3 4 Butterworth B (1979). "Hesitation and the production of verbal paraphasias and neologisms in jargon aphasia". Brain and Language. 8 (2): 133–61. doi:10.1016/0093-934x(79)90046-4. PMID 487066. S2CID 39339730.

- ↑ Garzon M, Semenza M, Meneghello F, Bencini G, Semenza C (2011). "Target-Unrelated Verbal Paraphasias: A Case Study" (PDF). Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 23: 142–3. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.210 .

- 1 2 Lewis FC, Soares L (2000). "Relationship between Semantic Paraphasias and Related Nonverbal Factors". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 91 (2): 366–72. doi:10.2466/pms.2000.91.2.366. PMID 11065295. S2CID 755716.

- ↑ Boyle M. 1988. Reducing Phonemic Paraphasias in the Connected Speech of a Conduction Aphasic Subject. In Clinical Aphasiology Conference, pp. 379-93. Cape Cod, MA

- ↑ T. Picht, S. M. Krieg, N. Sollmann, J. Rösler, B. Niraula, T. Neuvonen, P. Savolainen, P. Lioumis, Pantelis, J. P. Mäkelä, V. Deletis, B. Meyer, P. Vajkoczy, and F. Ringel, A comparison of language mapping by preoperative navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation and direct cortical stimulation during awake surgery, Neurosurgery 72, 808–819 (2013).