The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance of 32 member states—30 European and 2 North American. Established in the aftermath of World War II, the organization implements the North Atlantic Treaty, signed in Washington, D.C., on 4 April 1949. NATO is a collective security system: its independent member states agree to defend each other against attacks by third parties. During the Cold War, NATO operated as a check on the threat posed by the Soviet Union. The alliance remained in place after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, and has been involved in military operations in the Balkans, the Middle East, South Asia and Africa. The organization's motto is animus in consulendo liber. The organization's strategic concepts include deterrence.

The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) is a post–Cold War, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) institution. The EAPC is a multilateral forum created to improve relations between NATO and non-NATO countries in Europe and Central Asia. States meet to cooperate and discuss political and security issues. It was formed on 29 May 1997 at a Ministers’ meeting held in Sintra, Portugal, as the successor to the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC), which was created in 1991.

The State Partnership Program (SPP) is a joint program of the United States Department of Defense (DoD) and the individual states, territories, and District of Columbia. The program and the concept originated in 1993 as a simplified form of the previously established (1992) Joint Contact Team Program (JCTP). The JCTP aimed at assisting former Warsaw Pact and Soviet Union Republics, now independent, to form democracies and defense forces of their own. It featured long-term presence of extensive and expensive teams of advisory specialists. The SPP shortened the advisory presence to a United States National Guard unit of a designated state, called a partner, which would conduct joint exercises with the host. It is cheaper, has a lesser American presence, and can comprise contacts with civilian agencies. Today both programs are funded.

The 2006 Riga summit or the 19th NATO Summit was a NATO summit held in the Olympic Sports Centre, Riga, Latvia from 28 to 29 November 2006. The most important topics discussed were the War in Afghanistan and the future role and borders of the alliance. Further, the summit focused on the alliance's continued transformation, taking stock of what has been accomplished since the 2002 Prague Summit. NATO also committed itself to extending further membership invitations in the upcoming 2008 Bucharest Summit. This summit was the first NATO summit held on the territory of the Baltic states.

Georgia and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) enjoy cordial relations. Georgia is not currently a member of NATO, but has been promised by NATO to be admitted in the future.

Romania joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on March 29, 2004, following the decision taken at the Prague Summit, in November 2002. For Romania, this has represented a major evolution, with decisive influence upon the foreign and domestic policy of Romania. NATO membership represents the guarantee of security and external stability, which is vital for ensuring the prosperous development of the country. Romania is playing an active role in promoting the values and objectives of the Alliance, by both participating in the operations and missions of the Alliance and involving in its conceptual initiatives and evolutions.

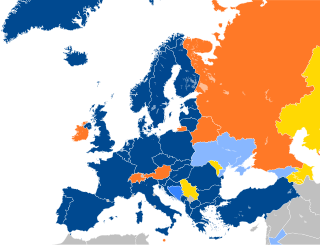

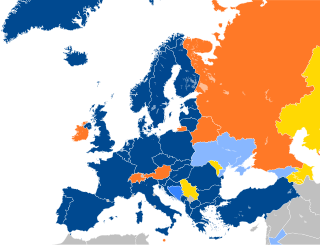

NATO is a military alliance of thirty-two European and North American countries that constitutes a system of collective defense. The process of joining the alliance is governed by Article 10 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which allows for the invitation of "other European States" only and by subsequent agreements. Countries wishing to join must meet certain requirements and complete a multi-step process involving political dialog and military integration. The accession process is overseen by the North Atlantic Council, NATO's governing body. NATO was formed in 1949 with twelve founding members and has added new members ten times. The first additions were Greece and Turkey in 1952. In May 1955, West Germany joined NATO, which was one of the conditions agreed to as part of the end of the country's occupation by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, prompting the Soviet Union to form its own collective security alliance later that month. Following the end of the Franco regime, newly democratic Spain chose to join NATO in 1982.

Relations between the NATO military alliance and the Russian Federation were established in 1991 within the framework of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council. In 1994, Russia joined the Partnership for Peace program, and on 27 May 1997, the NATO–Russia Founding Act (NRFA) was signed at the 1997 Paris NATO Summit in France, enabling the creation of the NATO–Russia Permanent Joint Council (NRPJC). Through the early part of 2010s NATO and Russia signed several additional agreements on cooperation. The NRPJC was replaced in 2002 by the NATO–Russia Council (NRC), which was established in an effort to partner on security issues and joint projects together.

The accession of Albania to NATO took place in 2009. Albania's relationship with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) began in 1992 when it joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council. In 1994, it entered NATO's Partnership for Peace, which began Albania's process of accession into the alliance. In 1999, the country received a Membership Action Plan (MAP). The country received an invitation to join at the 2008 Bucharest Summit and became a full member on April 1, 2009.

The 1994 Brussels summit was the 13th NATO summit bringing the leaders of member nations together at the same time. The formal sessions and informal meetings in Brussels, Belgium took place on 10–11 January 1994.

NATO maintains foreign relations with many non-member countries across the globe. NATO runs a number of programs which provide a framework for the partnerships between itself and these non-member nations, typically based on that country's location. These include the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council and the Partnership for Peace.

The Partnership for Peace Consortium is a network of over 800 defense academies and security studies institutes across 60 countries. Founded in 1998 during the NATO Summit, the PfPC was chartered to promote defense institution building and foster regional stability through multinational education and research, which the PfPC accomplishes via a network of educators and researchers. It is based at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch, Germany. According to the PfPC Annual Report of 2012, in 2012 eight hundred defense academies and security studies institutes in 59 countries worked with the PfPC in 69 defense education/defense institution building and policy-relevant events. The Consortium publishes an academic quarterly journal CONNECTIONS in English and Russian. The journal is run by an international Editorial Board of experts and is distributed to over 1,000 institutions in 54 countries.

Ireland and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have had a formal relationship since 1999, when Ireland joined as a member of the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) program and signed up to NATO's Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC). To date, Ireland has not sought to become a member of NATO due to its traditional policy of military neutrality.

Serbia is a member state of several international organizations :

The relationship between Azerbaijan and NATO started in 1992 when Azerbaijan joined the newly created North Atlantic Cooperation Council. Considerable partnership between NATO and Azerbaijan dates back to 1994, when the latter joined Partnership for Peace program. Azerbaijan established a diplomatic Mission to NATO in 1997 by the Presidential Decree on 21 November.

Withdrawal from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is the legal and political process whereby a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation withdraws from the North Atlantic Treaty, and thus the country in question ceases to be a member of NATO. The formal process is stated in article 13 of the Treaty. This says that any country that wants to leave must send the United States a "notice of denunciation", which the U.S. would then pass on to the other Allies. After a one-year waiting period, the country that wants to leave would be out.

The European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) are two main treaty-based Western organisations for cooperation between member states, both headquartered in Brussels, Belgium. Their natures are different and they operate in different spheres: NATO is a purely intergovernmental organisation functioning as a military alliance, which serves to implement article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty on collective territorial defence. The EU on the other hand is a partly supranational and partly intergovernmental sui generis entity akin to a confederation that entails wider economic and political integration. Unlike NATO, the EU pursues a foreign policy in its own right—based on consensus, and member states have equipped it with tools in the field of defence and crisis management; the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) structure.

Armenia and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have maintained a formal relationship since 1992, when Armenia joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council. Armenia officially established bilateral relations with NATO in 1994 when it became a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme. In 2002, Armenia became an Associate Member of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.

Cyprus is one of four European Union (EU) member states which is not a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the only one not to participate in NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) program. The others are Austria, Ireland and Malta.

Malta and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have a close relationship. Malta is one of four members of the European Union that are not members of NATO, the others being Austria, Cyprus and Ireland. Malta has had formal relations with NATO since 1995, when it joined the Partnership for Peace programme. While it withdrew in 1996, it rejoined as a member in 2008.