Related Research Articles

Alexander of Aphrodisias was a Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek commentators on the writings of Aristotle. He was a native of Aphrodisias in Caria and lived and taught in Athens at the beginning of the 3rd century, where he held a position as head of the Peripatetic school. He wrote many commentaries on the works of Aristotle, extant are those on the Prior Analytics, Topics, Meteorology, Sense and Sensibilia, and Metaphysics. Several original treatises also survive, and include a work On Fate, in which he argues against the Stoic doctrine of necessity; and one On the Soul. His commentaries on Aristotle were considered so useful that he was styled, by way of pre-eminence, "the commentator".

Ibn Rushd, often Latinized as Averroes, was an Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the Western world as The Commentator and Father of Rationalism.

Hylomorphism is a philosophical doctrine developed by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, which conceives every physical entity or being (ousia) as a compound of matter (potency) and immaterial form (act), with the generic form as immanently real within the individual. The word is a 19th-century term formed from the Greek words ὕλη and μορφή. Hylomorphic theories of physical entities have been undergoing a revival in contemporary philosophy.

Averroism refers to a school of medieval philosophy based on the application of the works of 12th-century Andalusian philosopher Averroes, a commentator on Aristotle, in 13th-century Latin Christian scholasticism.

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja, best known by his Latinised name Avempace, was an Andalusi polymath, whose writings include works regarding astronomy, physics, and music, as well as philosophy, medicine, botany, and poetry.

This article covers the conversations between Islamic philosophy and Jewish philosophy, and mutual influence on each other in response to questions and challenges brought into wide circulation through Aristotelianism, Neo-platonism, and the Kalam, focusing especially on the period from 800–1400 CE.

On the Soul is a major treatise written by Aristotle c. 350 BC. His discussion centres on the kinds of souls possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their different operations. Thus plants have the capacity for nourishment and reproduction, the minimum that must be possessed by any kind of living organism. Lower animals have, in addition, the powers of sense-perception and self-motion (action). Humans have all these as well as intellect.

In philosophy, potentiality and actuality are a pair of closely connected principles which Aristotle used to analyze motion, causality, ethics, and physiology in his Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, and De Anima.

Metaphysics is one of the principal works of Aristotle, in which he develops the doctrine that he calls First Philosophy. The work is a compilation of various texts treating abstract subjects, notably substance theory, different kinds of causation, form and matter, the existence of mathematical objects and the cosmos, which together constitute much of the branch of philosophy later known as metaphysics.

The Summa Theologiae or Summa Theologica, often referred to simply as the Summa, is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all of the main theological teachings of the Catholic Church, intended to be an instructional guide for theology students, including seminarians and the literate laity. Presenting the reasoning for almost all points of Christian theology in the West, topics of the Summa follow the following cycle: God; Creation, Man; Man's purpose; Christ; the Sacraments; and back to God.

Nous, or Greek νοῦς, sometimes equated to intellect or intelligence, is a concept from classical philosophy for the faculty of the human mind necessary for understanding what is true or real.

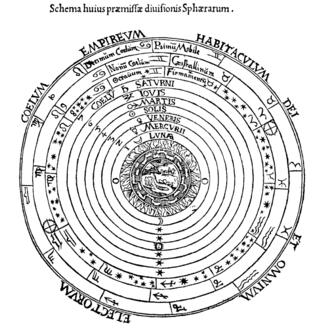

In medieval philosophy, the active intellect is the formal (morphe) aspect of the intellect (nous), according to the Aristotelian theory of hylomorphism. The nature of the active intellect was a major theme of late classical and medieval philosophy. Various thinkers sought to reconcile their commitment to Aristotle's account of the body and soul to their own theological commitments. At stake in particular was in what way Aristotle's account of an incorporeal soul might contribute to understanding of deity and creation.

The philosophy of self examines the idea of the self at a conceptual level. Many different ideas on what constitutes self have been proposed, including the self being an activity, the self being independent of the senses, the bundle theory of the self, the self as a narrative center of gravity, and the self as a linguistic or social construct rather than a physical entity. The self is also an important concept in Eastern philosophy, including Buddhist philosophy.

Nicoletto Vernia was an Italian Averroist philosopher, at the University of Padua.

An intelligible form in philosophy refers to a form that can be apprehended by the intellect, in contrast to sense perception. According to Ancient and Medieval philosophers, the intelligible forms are the things by which we understand. These are Genera and species. Genera and species are abstract concepts, not concrete objects. For example, “animal”, “man” and “horse” are general terms that do not refer to any particular individual in the natural world. Only specific animals, men and horses exist in reality.

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century, and in France, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne, in the last quarter of the 8th century. It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning. This is one of the defining characteristics in this time period. Understanding God was the focal point of study of the philosophers at that time, Muslim and Christian alike.

Aql al-Fa'al or Wahib al-Suwar is a kind of reason in Islamic philosophy and psychology. It is considered as the lowest level of celestial intelligences.

Aql bi al-Fi'l is a kind of intellect in Islamic philosophy. This level deals with readiness of the soul for acquiring the forms without receiving them again.

Aql bi al-Quwwah is the first stage of the intellect's hierarchy in Islamic philosophy. This kind of reason is also called the potential or material intellect. In philosophy thus kind of intellect also called as passive intellect.

The unity of the intellect , a philosophical theory proposed by the medieval Andalusian philosopher Averroes (1126–1198), asserted that all humans share the same intellect. Averroes expounded his theory in his long commentary on Aristotle's On the Soul to explain how universal knowledge is possible within the Aristotelian philosophy of mind. Averroes's theory was influenced by related ideas propounded by previous thinkers such as Aristotle himself, Plotinus, Al-Farabi, Avicenna and Avempace.

References

- ↑ Aristotle, De Anima, Bk. III, ch. 5 (430a10-25).

- ↑ Nicolas, S., Andrieu, B., Croizet, J.-C., Sanitioso, R. B., & Burman, J. T. (2013). Sick? Or slow? On the origins of intelligence as a psychological object. Intelligence, 41(5), 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2013.08.006 (This is an open access article, made freely available by Elsevier.)

- ↑ Kaufman, Alan S. (2009). IQ Testing 101 . New York: Springer Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8261-0629-2.Sattler, Jerome M. (2008). Assessment of Children: Cognitive Foundations. La Mesa, CA: Jerome M. Sattler, Publisher. inside back cover. ISBN 978-0-9702671-4-6.

- ↑ ( Craig 1998 , p. 556)

- ↑ ( Chase 2008 , p. 28)