Related Research Articles

Robert Bellarmine, SJ was an Italian Jesuit and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was canonized a saint in 1930 and named Doctor of the Church, one of only 37. He was one of the most important figures in the Counter-Reformation.

Giordano Bruno was an Italian philosopher, poet, cosmological theorist and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which conceptually extended to include the then-novel Copernican model. He proposed that the stars were distant suns surrounded by their own planets (exoplanets), and he raised the possibility that these planets might foster life of their own, a cosmological position known as cosmic pluralism. He also insisted that the universe is infinite and could have no center.

The Inquisition was a judicial procedure and a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, but convictions of unrepentant heresy were handed over to the secular courts, which generally resulted in execution or life imprisonment. The Inquisition had its start in the 12th-century Kingdom of France, with the aim of combating religious deviation, particularly among the Cathars and the Waldensians. The inquisitorial courts from this time until the mid-15th century are together known as the Medieval Inquisition. Other groups investigated during the Medieval Inquisition, which primarily took place in France and Italy, include the Spiritual Franciscans, the Hussites, and the Beguines. Beginning in the 1250s, inquisitors were generally chosen from members of the Dominican Order, replacing the earlier practice of using local clergy as judges.

The Medieval Inquisition was a series of Inquisitions from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). The Medieval Inquisition was established in response to movements considered apostate or heretical to Roman Catholicism, in particular Catharism and Waldensians in Southern France and Northern Italy. These were the first movements of many inquisitions that would follow.

Pantheism is the philosophical religious belief that reality, the universe, and nature are identical to divinity or a supreme entity. The physical universe is thus understood as an immanent deity, still expanding and creating, which has existed since the beginning of time. The term pantheist designates one who holds both that everything constitutes a unity and that this unity is divine, consisting of an all-encompassing, manifested god or goddess. All astronomical objects are thence viewed as parts of a sole deity.

The Roman Inquisition, formally Suprema Congregatio Sanctae Romanae et Universalis Inquisitionis, was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes according to Catholic law and doctrine, relating to Catholic religious life or alternative religious or secular beliefs. It was established in 1542 by the leader of the Catholic Church, Pope Paul III. In the period after the Medieval Inquisition, it was one of three different manifestations of the wider Catholic Inquisition, the other two being the Spanish Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition.

The year 1600 CE in science and technology included some significant events.

Naturalistic pantheism, also known as scientific pantheism, is a form of pantheism. It has been used in various ways such as to relate God or divinity with concrete things, determinism, or the substance of the universe. God, from these perspectives, is seen as the aggregate of all unified natural phenomena. The phrase has often been associated with the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza, although academics differ on how it is used. Natural pantheists don’t believe in any God, though they do worship the universe as if it was one. They believe in science, hence the name scientific pantheist, instead of a deity.

Konrad von Marburg was a medieval German Catholic priest and nobleman. He is perhaps best known as the spiritual director of Elizabeth of Hungary.

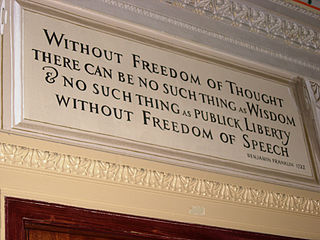

Freedom of thought is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Hylozoism is the philosophical doctrine according to which all matter is alive or animated, either in itself or as participating in the action of a superior principle, usually the world-soul. The theory holds that matter is unified with life or spiritual activity. The word is a 17th-century term formed from the Greek words ὕλη and ζωή, which was coined by the English Platonist philosopher Ralph Cudworth in 1678.

The Galileo affair began around 1610 and culminated with the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633. Galileo was prosecuted for his support of heliocentrism, the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the centre of the universe.

Heresy in Christianity denotes the formal denial or doubt of a core doctrine of the Christian faith as defined by one or more of the Christian churches.

Renaissance magic was a resurgence in Hermeticism and Neo-Platonic varieties of the magical arts which arose along with Renaissance humanism in the 15th and 16th centuries CE. During the Renaissance period, magic and occult practices underwent significant changes that reflected shifts in cultural, intellectual, and religious perspectives. C. S. Lewis, in his work on English literature, highlighted the transformation in how magic was perceived and portrayed. In medieval stories, magic had a fantastical and fairy-like quality, while in the Renaissance, it became more complex and tied to the idea of hidden knowledge that could be explored through books and rituals. This change is evident in the works of authors like Spenser, Marlowe, Chapman, and Shakespeare, who treated magic as a serious and potentially dangerous pursuit.

The Monument to Giordano Bruno, created by Ettore Ferrari, was erected in 1889 at Campo de' Fiori square in Rome, Italy, to commemorate the italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, who was burned there in 1600. Since its inception the idea of a monument dedicated to the executed heretic located in Rome, once the capital of the Papal States, has generated controversy between anti-clerical and those more aligned with the Roman Catholic church.

5148 Giordano, provisional designation 5557 P-L, is a background asteroid from the outer regions of the asteroid belt, approximately 8 kilometers in diameter. It was discovered on 17 October 1960, by Dutch astronomer couple Ingrid and Cornelis van Houten on photographic plates taken by Dutch–American astronomer Tom Gehrels at the Palomar Observatory in California, United States. It was named for Italian friar and heretic Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in Rome in 1600. The presumably carbonaceous Themistian asteroid has a rotation period of 7.8 hours and possibly an elongated shape.

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

The relationship between science and the Catholic Church is a widely debated subject. Historically, the Catholic Church has been a patron of sciences. It has been prolific in the foundation and funding of schools, universities, and hospitals, and many clergy have been active in the sciences. Some historians of science such as Pierre Duhem credit medieval Catholic mathematicians and philosophers such as John Buridan, Nicole Oresme, and Roger Bacon as the founders of modern science. Duhem found "the mechanics and physics, of which modern times are justifiably proud, to proceed by an uninterrupted series of scarcely perceptible improvements from doctrines professed in the heart of the medieval schools." Historian John Heilbron says that “The Roman Catholic Church gave more financial and social support to the study of astronomy for over six centuries, from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment, than any other, and probably all, other Institutions.” The conflict thesis and other critiques emphasize the historical or contemporary conflict between the Catholic Church and science, citing, in particular, the trial of Galileo as evidence. For its part, the Catholic Church teaches that science and the Christian faith are complementary, as can be seen from the Catechism of the Catholic Church which states in regards to faith and science:

Though faith is above reason, there can never be any real discrepancy between faith and reason. Since the same God who reveals mysteries and infuses faith has bestowed the light of reason on the human mind, God cannot deny himself, nor can truth ever contradict truth. ... Consequently, methodical research in all branches of knowledge, provided it is carried out in a truly scientific manner and does not override moral laws, can never conflict with the faith, because the things of the world and the things of faith derive from the same God. The humble and persevering investigator of the secrets of nature is being led, as it were, by the hand of God despite himself, for it is God, the conserver of all things, who made them what they are.

Galileo is a 1968 Italian–Bulgarian biographical drama film directed by Liliana Cavani. It depicts the life of Galileo Galilei and particularly his conflicts with the Catholic Church over his scientific theories.

A number of Christian writers have examined the concept of pandeism, and these have generally found it to be inconsistent with core principles of Christianity. The Roman Catholic Church, for example, condemned the Periphyseon of John Scotus Eriugena, later identified by physicist and philosopher Max Bernhard Weinstein as presenting a pandeistic theology, as appearing to obscure the separation of God and creation. The Church similarly condemned elements of the thought of Giordano Bruno which Weinstein and others determined to be pandeistic.

References

- ↑ "What Was the Charge Against Socrates?" Retrieved September 1, 2009

- ↑ Gatti, Hilary. Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Cornell University Press, 2002, 1, ISBN 0-801-48785-4

- ↑ Birx, H. James. "Giordano Bruno" The Harbinger, Mobile, AL, 11 November 1997. "Bruno was burned to death at the stake for his pantheistic stance and cosmic perspective."

- ↑ Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition , Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964, p. 450

- ↑ Michael J. Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750–1900, Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 10, "[Bruno's] sources... seem to have been more numerous than his followers, at least until the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century revival of interest in Bruno as a supposed 'martyr for science.' It is true that he was burned at the stake in Rome in 1600, but the church authorities guilty of this action were almost certainly more distressed at his denial of Christ's divinity and alleged diabolism than at his cosmological doctrines."

- ↑ Adam Frank (2009). The Constant Fire: Beyond the Science vs. Religion Debate, University of California Press, p. 24, "Though Bruno may have been a brilliant thinker whose work stands as a bridge between ancient and modern thought, his persecution cannot be seen solely in light of the war between science and religion."

- ↑ White, Michael (2002). The Pope and the Heretic: The True Story of Giordano Bruno, the Man who Dared to Defy the Roman Inquisition, p. 7. Perennial, New York. "This was perhaps the most dangerous notion of all... If other worlds existed with intelligent beings living there, did they too have their visitations? The idea was quite unthinkable."

- ↑ Shackelford, Joel (2009). "Myth 7 That Giordano Bruno was the first martyr of modern science". In Numbers, Ronald L. (ed.). Galileo goes to jail and other myths about science and religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 66. "Yet the fact remains that cosmological matters, notably the plurality of worlds, were an identifiable concern all along and appear in the summary document: Bruno was repeatedly questioned on these matters, and he apparently refused to recant them at the end.14 So, Bruno probably was burned alive for resolutely maintaining a series of heresies, among which his teaching of the plurality of worlds was prominent but by no means singular."

- ↑ Martínez, Alberto A. (2018). Burned Alive: Giordano Bruno, Galileo and the Inquisition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1780238968.

- ↑ Gatti, Hilary (2002). Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0801487859 . Retrieved 21 March 2014.

For Bruno was claiming for the philosopher a principle of free thought and inquiry which implied an entirely new concept of authority: that of the individual intellect in its serious and continuing pursuit of an autonomous inquiry… It is impossible to understand the issue involved and to evaluate justly the stand made by Bruno with his life without appreciating the question of free thought and liberty of expression. His insistence on placing this issue at the center of both his work and of his defense is why Bruno remains so much a figure of the modern world. If there is, as many have argued, an intrinsic link between science and liberty of inquiry, then Bruno was among those who guaranteed the future of the newly emerging sciences, as well as claiming in wider terms a general principle of free thought and expression.

- ↑ Montano, Aniello (2007). Antonio Gargano (ed.). Le deposizioni davanti al tribunale dell'Inquisizione. Napoli: La Città del Sole. p. 71.

In Rome, Bruno was imprisoned for seven years and subjected to a difficult trial that analyzed, minutely, all his philosophical ideas. Bruno, who in Venice had been willing to recant some theses, become increasingly resolute and declared on 21 December 1599 that he 'did not wish to repent of having too little to repent, and in fact did not know what to repent.' Declared an unrepentant heretic and excommunicated, he was burned alive in the Campo dei Fiori in Rome on Ash Wednesday, 17 February 1600. On the stake, along with Bruno, burned the hopes of many, including philosophers and scientists of good faith like Galileo, who thought they could reconcile religious faith and scientific research, while belonging to an ecclesiastical organization declaring itself to be the custodian of absolute truth and maintaining a cultural militancy requiring continual commitment and suspicion.

- ↑ "Tommaso Campanella" - first published Wed Aug 31, 2005" at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Retrieved September 1, 2009

- ↑

- Scruton, Roger (2002). Spinoza: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-19-280316-0.

- Nadler, Steven M. (2001). Spinoza: A Life. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2, 7, 120. ISBN 978-0-521-00293-6.

- Smith, Steven B. (2003). Spinoza's Book of Life: Freedom and Redemption in the Ethics. Yale University Press. p. xx. ISBN 978-0-300-12849-9.

- Nadler, Steven (2020). "Baruch Spinoza". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Spinoza, Benedictus de (4 September 1989). Tractatus Theologico-Politicus: Gebhardt Edition 1925. BRILL. ISBN 9004090991 . Retrieved 4 September 2019– via Google Books.

- ↑ Scruton, Roger (2002). Spinoza: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-280316-0.

- ↑ See: Jonathan Israel, “The Banning of Spinoza's Works in the Dutch Republic (1670–1678)”, in: Wiep van Bunge and Wim Klever (eds.) Disguised and Overt Spinozism around 1700 (Leiden, 1996), 3-14 (online).