Related Research Articles

A microlith is a small stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 35,000 to 3,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia. The microliths were used in spear points and arrowheads.

In archaeology, in particular of the Stone Age, lithic reduction is the process of fashioning stones or rocks from their natural state into tools or weapons by removing some parts. It has been intensely studied and many archaeological industries are identified almost entirely by the lithic analysis of the precise style of their tools and the chaîne opératoire of the reduction techniques they used.

In archaeology, lithic analysis is the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts using basic scientific techniques. At its most basic level, lithic analyses involve an analysis of the artifact's Morphology (archaeology), the measurement of various physical attributes, and examining other visible features.

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE. They are believed to have originated from the northern Philippines, either directly, via the Mariana Islands, or both. They were notable for their distinctive geometric designs on dentate-stamped pottery, which closely resemble the pottery recovered from the Nagsabaran archaeological site in northern Luzon. The Lapita intermarried with the Papuan populations to various degrees, and are the direct ancestors of the Austronesian peoples of Polynesia, eastern Micronesia, and Island Melanesia.

In the archaeology of the Stone Age, an industry or technocomplex is a typological classification of stone tools.

Wilton is a term archaeologists use to generalize archaeological sites and cultures that share similar stone and non-stone technology dating from 8,000-4,000 years ago. Archaeologists often refer to Wilton as a technocomplex, or Industry. Technological industries are defined by a common tradition of stone tool assemblages, but these technological industries extend to common cultural behaviors. As such, archaeologists use these industries to define a discrete cultural taxonomy. However, technological industries have the potential to generalize different cultures and communities at regional scales that, in more local settings, are distinguishable in both technology and cultural behaviors.

Hoabinhian is a lithic techno-complex of archaeological sites associated with assemblages in Southeast Asia from late Pleistocene to Holocene, dated to c. 10,000–2000 BCE. It is attributed to hunter-gatherer societies of the region and their technological variability over time is poorly understood. In 2016 a rockshelter was identified in Yunnan (China), where artifacts belonging to the Hoabinhian technocomplex were recognized. These artifacts date from 41,500 BCE.

The prehistory of Australia is the period between the first human habitation of the Australian continent and the colonisation of Australia in 1788, which marks the start of consistent written documentation of Australia. This period has been variously estimated, with most evidence suggesting that it goes back between 50,000 and 65,000 years. This era is referred as prehistory rather than history because knowledge of this time period does not derive from written documentation. However, some argue that Indigenous oral tradition should be accorded an equal status.

Retouch is the act of producing scars on a stone flake after the ventral surface has been created. It can be done to the edge of an implement in order to make it into a functional tool, or to reshape a used tool. Retouch can be a strategy to reuse an existing lithic artifact and enable people to transform one tool into another tool. Depending on the form of classification that one uses, it may be argued that retouch can also be conducted on a core-tool, if such a category exists, such as a hand-axe.

Australian archaeology is a large sub-field in the discipline of archaeology. Archaeology in Australia takes four main forms: Aboriginal archaeology, historical archaeology, maritime archaeology and the archaeology of the contemporary past. Bridging these sub-disciplines is the important concept of cultural heritage management, which encompasses Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sites, historical sites, and maritime sites.

Roger Llewellyn Dunmore Cribb was an Australian archaeologist and anthropologist who specialised in documenting and modelling spatial patterns and social organisation of nomadic peoples. He is noted for conducting early fieldwork amongst the nomadic pastoralists of Anatolia, Turkey; writing a book on the archaeology of these nomads; pioneering Australian archaeology and anthropologies' use of geographical information systems, plus genealogical software; and conducting later fieldwork documenting the cultural landscapes of the Aboriginal peoples of Cape York Peninsula.

The Soanian culture is a prehistoric technological culture from the Siwalik Hills in the Indian subcontinent. It is named after the Soan Valley in Pakistan. Soanian sites are found along the Siwalik region in present-day India, Nepal and Pakistan. The Soanian culture has been approximated to have taken place during the Middle Pleistocene period or the mid-Holocene epoch (Northgrippian). Debates still goes on today regarding the exact period occupied by the culture due to artefacts often being found in non-datable surface context. This culture was first discovered and named by the anthropology and archaeology team led by Helmut De Terra and Thomas Thomson Paterson. Soanian artifacts were manufactured on quartzite pebbles, cobbles, and occasionally on boulders, all derived from various fluvial sources on the Siwalik landscape. Soanian assemblages generally comprise varieties of choppers, discoids, scrapers, cores, and numerous flake type tools, all occurring in varying typo-technological frequencies at different sites.

Karim Sadr is an archaeologist contributing to research in southern Africa. He is the author of over 60 academic articles, a book and two edited volumes. While Sadr has contributed to the Kalahari Debate, his more recent work has focused on historical revision, re-examining the acquisition of domesticated animals and pottery in southern Africa by Hunter-gatherer. His work is reintroducing the term Neolithic back into southern African archaeological discourse from which it had previously been removed.

The University of Queensland Anthropology Museum is located in Brisbane, Australia. It houses the largest university collection of ethnographic material culture in Australia.

Valerie Attenbrow is principal research scientist in the Anthropology Research Section of the Australian Museum, a position she has held since 1989.

Kilu Cave is a paleoanthropological site located on Buka Island in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea. Kilu Cave is located at the base of a limestone cliff, 65 m (213 ft) from the modern coastline. With evidence for human occupation dating back to 30,000 years, Kilu Cave is the earliest known site for human occupation in the Solomon Islands archipelago. The site is the oldest proof of paleolithic people navigating the open ocean i.e. navigating without land in sight. To travel from Nissan island to Buka requires crossing of at least 60 kilometers of open sea. The presence of paleolithic people at Buka therefore is at the same time evidence for the oldest and the longest paleolithic sea travel known so far.

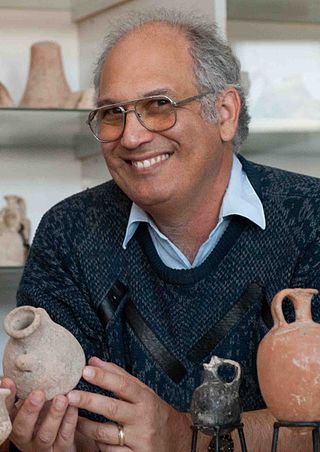

Steven A Rosen is the Canada Chair in Near Eastern Archaeology in the Archaeological Division of the Department of Bible, Archaeology and Ancient Near East at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He serves as the Vice President for External Affairs. His research has focused on two general areas, the continued use of chipped stone tools in the periods during which metals were already exploited, and the archaeology of mobile pastoralists, using the Negev as an in-depth case study.

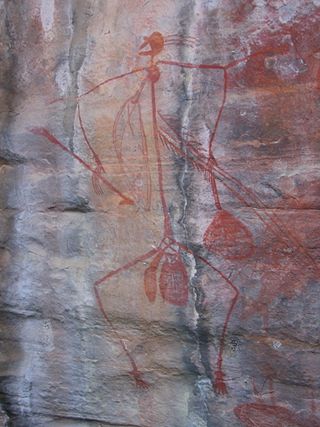

Madjedbebe is a sandstone rock shelter in Arnhem Land, in the Northern Territory of Australia, possibly the oldest site of human habitation in Australia. It is located about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from the coast. It is part of the lands traditionally inhabited by the Mirarr, an Aboriginal Australian clan of the Gaagudju people, of the Gunwinyguan language group. Although it is surrounded by the World Heritage Listed Kakadu National Park, Madjedbebe itself is located within the Jabiluka Mineral Leasehold.

Dr Josephine McDonald is an Australian archaeologist and Director of the Centre for Rock Art Research + Management at the University of Western Australia. McDonald is primarily known for her influence in the field of rock art research and her collaborative research with Australian Aboriginal communities.

Lynley A. Wallis is an Australian archaeologist and Associate Professor at Griffith University. She is a specialist in palaeoenvironmental reconstruction through the analysis of phytoliths.

References

- ↑ The University of Sydney "Major gifts lead to exciting new professorial appointments"

- ↑ Books by Peter Hiscock on Amazon

- ↑ Hiscock, Peter and Wallis, Lynley (2005). "Pleistocene settlement of deserts from an Australian perspective". In P. Veth, M. Smith and P. Hiscock (eds) Desert Peoples: archaeological perspectives. Blackwell. Pp. 34-57.

- ↑ Hiscock, Peter; Attenbrow, Val (July 1998). "Early Holocene backed artefacts from Australia". Archaeology in Oceania. 33 (2): 49–62. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1998.tb00404.x. hdl: 1885/41382 . ISSN 0728-4896.

- ↑ Robertson, Gail; Attenbrow, Val; Hiscock, Peter (June 2009). "Multiple uses for Australian backed artefacts". Antiquity. 83 (320): 296–308. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00098446. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 162566863.

- ↑ Hiscock, Peter (May 2021). "Small Signals: Comprehending the Australian Microlithic as Public Signalling". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 31 (2): 313–324. doi:10.1017/S0959774320000335. ISSN 0959-7743. S2CID 233291854.

- ↑ Hiscock, P. and Faulkner, P. (2006) "Dating the dreaming? Creation of myths and rituals for mounds along the northern Australian coastline". Cambridge Archaeological Journal16:209-22.

- ↑ "Peter Hiscock awarded new ARC funding Australian National University"

- ↑ Hiscock, Peter. (2008). Archaeology of Ancient Australia. Routledge: London. ISBN 0-415-33811-5

- ↑ Fagan, Brian (2008) "Book review: Archaeology of Ancient Australia by Peter Hiscock". Australian Archaeology66: 69-70

- ↑ Fran Molloy, "Ancient Australia not written in stone", ABC News in Science

- ↑ "Review of Archaeology of Ancient Australia", Antiquity Volume 82 Issue 317. September 2008

- ↑ Australian Archaeological Association, Awards