Related Research Articles

Denis Diderot was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the Encyclopédie along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during the Age of Enlightenment.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher (philosophe), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolution and the development of modern political, economic, and educational thought.

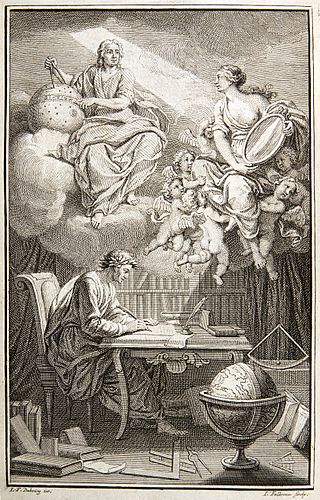

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that occurred in Europe, especially Western Europe, in the 17th and 18th centuries, with global influences and effects. The Enlightenment included a range of ideas centered on the value of human happiness, the pursuit of knowledge obtained by means of reason and the evidence of the senses, and ideals such as natural law, liberty, progress, toleration, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state.

François-Marie Arouet was a French Enlightenment writer, philosopher (philosophe) and historian. Known by his nom de plumeM. de Voltaire, he was famous for his wit, in addition to his criticism of Christianity—especially of the Roman Catholic Church—and of slavery. Voltaire was an advocate of freedom of speech, freedom of religion and separation of church and state.

Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach, known as d'Holbach, was a Franco-German philosopher, encyclopedist and writer, who was a prominent figure in the French Enlightenment. He was born Paul Heinrich Dietrich in Edesheim, near Landau in the Rhenish Palatinate, but lived and worked mainly in Paris, where he kept a salon. He helped in the dissemination of "Protestant and especially German thought", particularly in the field of the sciences, but was best known for his atheism and for his voluminous writings against religion, the most famous of them being The System of Nature (1770) and The Universal Morality (1776).

Claude Adrien Helvétius was a French philosopher, freemason and littérateur.

The Counter-Enlightenment refers to a loose collection of intellectual stances that arose during the European Enlightenment in opposition to its mainstream attitudes and ideals. The Counter-Enlightenment is generally seen to have continued from the 18th century into the early 19th century, especially with the rise of Romanticism. Its thinkers did not necessarily agree to a set of counter-doctrines but instead each challenged specific elements of Enlightenment thinking, such as the belief in progress, the rationality of all humans, liberal democracy, and the increasing secularisation of society.

"Answering the Question: What Is Enlightenment?", often referred to simply as "What Is Enlightenment?", is a 1784 essay by the philosopher Immanuel Kant. In the December 1784 publication of the Berlinische Monatsschrift, edited by Friedrich Gedike and Johann Erich Biester, Kant replied to the question posed a year earlier by the Reverend Johann Friedrich Zöllner, who was also an official in the Prussian government. Zöllner's question was addressed to a broad intellectual public community, in reply to Biester's essay entitled: "Proposal, not to engage the clergy any longer when marriages are conducted" and a number of leading intellectuals replied with essays, of which Kant's is the most famous and has had the most impact. Kant's opening paragraph of the essay is a much-cited definition of a lack of enlightenment as people's inability to think for themselves due not to their lack of intellect, but lack of courage.

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual and philosophical fervor in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution and the creation of the United States of America. The American Enlightenment was influenced by the 17th- and 18th-century Age of Enlightenment in Europe and native American philosophy. According to James MacGregor Burns, the spirit of the American Enlightenment was to give Enlightenment ideals a practical, useful form in the life of the nation and its people.

The Dictionnaire philosophique is an encyclopedic dictionary published by the Enlightenment thinker Voltaire in 1764. The alphabetically arranged articles often criticize the Roman Catholic Church, Judaism, Islam, and other institutions. The first edition, released in June 1764, went by the name of Dictionnaire philosophique portatif. It was 344 pages and consisted of 73 articles. Later versions were expanded into two volumes consisting of 120 articles.

18th-century French literature is French literature written between 1715, the year of the death of King Louis XIV of France, and 1798, the year of the coup d'État of Bonaparte which brought the Consulate to power, concluded the French Revolution, and began the modern era of French history. This century of enormous economic, social, intellectual and political transformation produced two important literary and philosophical movements: during what became known as the Age of Enlightenment, the Philosophes questioned all existing institutions, including the church and state, and applied rationalism and scientific analysis to society; and a very different movement, which emerged in reaction to the first movement; the beginnings of Romanticism, which exalted the role of emotion in art and life.

The Preliminary Discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot is the primer to Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de Gens de lettres, a collaborative collection of all the known branches of the arts and sciences of the 18th century French Enlightenment. The Preliminary Discourse was written by Jean Le Rond d'Alembert to describe the structure of the articles included in the Encyclopédie and their philosophy, as well as to give the reader a strong background in the history behind the works of the learned men who contributed to what became the most profound circulation of the knowledge of the time.

The Lumières was a cultural, philosophical, literary and intellectual movement beginning in the second half of the 17th century, originating in western Europe and spreading throughout the rest of Europe. It included philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza, David Hume, John Locke, Edward Gibbon, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, Pierre Bayle and Isaac Newton. This movement is influenced by the scientific revolution in southern Europe arising directly from the Italian renaissance with people like Galileo Galilei. Over time it came to mean the Siècle des Lumières, in English the Age of Enlightenment.

Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism is a book by Abbé Augustin Barruel, a French Jesuit priest. It was written and published in French in 1797–98, and translated into English in 1799.

Atheism, as defined by the entry in Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, is "the opinion of those who deny the existence of a God in the world. The simple ignorance of God doesn't constitute atheism. To be charged with the odious title of atheism one must have the notion of God and reject it." In the period of the Enlightenment, avowed and open atheism was made possible by the advance of religious toleration, but was also far from encouraged.

Deism, the religious attitude typical of the Enlightenment, especially in France and England, holds that the only way the existence of God can be proven is to combine the application of reason with observation of the world. A Deist is defined as "One who believes in the existence of a God or Supreme Being but denies revealed religion, basing his belief on the light of nature and reason." Deism was often synonymous with so-called natural religion because its principles are drawn from nature and human reasoning. In contrast to Deism there are many cultural religions or revealed religions, such as Judaism, Trinitarian Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and others, which believe in supernatural intervention of God in the world; while Deism denies any supernatural intervention and emphasizes that the world is operated by natural laws of the Supreme Being.

Jacob Vernes was a Genevan theologian and Protestant pastor in Geneva, famous for his correspondence with Voltaire and Rousseau.

Questions sur les Miracles, also known as Lettres sur les Miracles, is a series of pamphlets published by the French philosopher and author Voltaire. In these pamphlets Voltaire expresses many themes, including primarily his arguments against other recent pamphlets that had discussed religious miracles. Voltaire, in his responses found it ridiculous that God would occasionally violate natural laws for a particular reason. Voltaire's first pamphlet was published in July 1765, and during the course of that year, he published nineteen more. The pamphlets were published anonymously, and signed pseudonymously.

Alexandre Deleyre was an 18th-century French man of letters and translator from Latin. He was a friend of J.J. Rousseau, who used his translations of Lucretius for compositions.

The Enlightenment: An Interpretation is an influential two-volume history of the Age of Enlightenment by Peter Gay, published between 1966 and 1969. The first volume, subtitled "The Rise of Modern Paganism," won the National Book Award in 1967. The second volume, subtitled “The Science of Freedom," was published in 1969.

References

- The Philosophes

- Gay, Peter. The Enlightenment - An Interpretation 1: The Rise of Modern Paganism, (1995). ISBN 0-393-31302-6.

- Reill, Peter Hans and Ellen Judy Wilson. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment (2004)