Related Research Articles

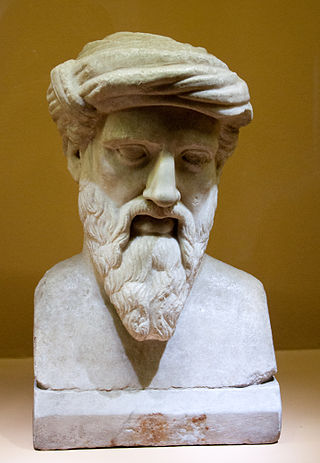

Pythagoras of Samos was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle, and, through them, the West in general. Knowledge of his life is clouded by legend. Modern scholars disagree regarding Pythagoras's education and influences, but they do agree that, around 530 BC, he travelled to Croton in southern Italy, where he founded a school in which initiates were sworn to secrecy and lived a communal, ascetic lifestyle. This lifestyle entailed a number of dietary prohibitions, traditionally said to have included aspects of vegetarianism.

Philolaus was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition and the most outstanding figure in the Pythagorean school. Pythagoras developed a school of philosophy that was dominated by both mathematics and mysticism. Most of what is known today about the Pythagorean astronomical system is derived from Philolaus's views. He may have been the first to write about Pythagorean doctrine. According to August Böckh (1819), who cites Nicomachus, Philolaus was the successor of Pythagoras.

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, in modern Calabria (Italy). Early Pythagorean communities spread throughout Magna Graecia.

Aesara of Lucania was a conjectured Pythagorean philosopher who may have written On Human Nature, a fragment of which is preserved by Stobaeus, although the majority of critical scholars follow Holger Thesleff in attributing it to Aresas, a male writer from Lucania who is also mentioned by Iamblichus in his Life of Pythagoras.

Iamblichus was an Arab neoplatonic philosopher. He determined a direction later taken by neoplatonism. Iamblichus was also the biographer of the Greek mystic, philosopher, and mathematician Pythagoras. In addition to his philosophical contributions, his Protrepticus is important for the study of the sophists because it preserved about ten pages of an otherwise unknown sophist known as the Anonymus Iamblichi.

Hippasus of Metapontum was a Greek philosopher and early follower of Pythagoras. Little is known about his life or his beliefs, but he is sometimes credited with the discovery of the existence of irrational numbers. The discovery of irrational numbers is said to have been shocking to the Pythagoreans, and Hippasus is supposed to have drowned at sea, apparently as a punishment from the gods for divulging this and crediting it to himself instead of Pythagoras which was the norm in Pythagorean society. However, the few ancient sources who describe this story either do not mention Hippasus by name or alternatively tell that Hippasus drowned because he revealed how to construct a dodecahedron inside a sphere. The discovery of irrationality is not specifically ascribed to Hippasus by any ancient writer.

Theano was a 6th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher. She has been called the wife or student of Pythagoras, although others see her as the wife of Brontinus. Her place of birth and the identity of her father is uncertain as well. Many Pythagorean writings were attributed to her in antiquity, including some letters and a few fragments from philosophical treatises, although these are all regarded as spurious by modern scholars.

Ocellus Lucanus was allegedly a Pythagorean philosopher, born in Lucania in Magna Graecia in the 6th century BC. Aristoxenus cites him along with another Lucanian by the name of Ocillo, in a work preserved by Iamblichus that lists 218 supposed Pythagoreans, which nonetheless contained some inventions, wrong attributions to non-Pythagoreans, and some names derived from earlier pseudopythagoric traditions.

Damo was a Pythagorean philosopher said by many to have been the daughter of Pythagoras and Theano.

Ancient Roman philosophy is philosophy as it was practiced in the Roman Republic and its successor state, the Roman Empire. Roman philosophy includes not only philosophy written in Latin, but also philosophy written in Greek in the late Republic and Roman Empire. Important early Latin-language writers include Lucretius, Cicero, and Seneca the Younger. Greek was a popular language for writing about philosophy, so much so that the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius chose to write his Meditations in Greek.

Perictione was the mother of the Greek philosopher Plato.

Hierocles was a Stoic philosopher. Very little is known about his life. Aulus Gellius mentions him as one of his contemporaries, and describes him as a "grave and holy man."

Eurytus was an eminent Pythagorean philosopher from Magna Graecia who Iamblichus in one passage describes as a native of Croton, while in another, he enumerates him among the Tarentine Pythagoreans.

Cleinias of Tarentum, Magna Graecia, was a Pythagorean philosopher, and a contemporary and friend of Plato, as appears from the story which Diogenes Laërtius gives on the authority of Aristoxenus, to the effect that Plato wished to burn all the writings of Democritus which he could collect, but was prevented by Cleinias and Amyclus of Heraclea. In his practice, Cleinias was a true Pythagorean. Thus, we hear that he used to assuage his anger by playing on his harp; and, when Prorus of Cyrene had lost all his fortune through a political revolution, Cleinias, who knew nothing of him except that he was a Pythagorean, took on himself the risk of a voyage to Cyrene, and supplied him with money to the full extent of his loss.

Myia was a Pythagorean philosopher and, according to later tradition, one of the daughters of Theano and Pythagoras.

Onatas was a Pythagorean philosopher who lived in or around the 5th century BC, possibly in either Croton or Tarentum in Magna Graecia. Nothing more is known about his life, but he is credited by Stobaeus as the author of a pseudonymous Neo-Pythagorean work from the 1st century BC or AD entitled On God and the Divine, which Stobaeus excerpts a long passage from. The author of the passage ("Pseudo-Onatas") argues against the belief in a single deity, on the basis that the universe itself is not God but only divine, but that God is a governing part of the universe. He argues that since there are many "powers" in the universe, therefore they must belong to different gods. Pseudo-Onatas also claimed that the earthy mixture of the body defiles the purity of the soul.

Protrepticus or, "Exhortation to Philosophy" is a lost philosophical work written by Aristotle in the mid-4th century BCE. The work was intended to encourage the reader to study philosophy. Although the Protrepticus was one of Aristotle's most famous works in antiquity, it did not survive except in fragments and ancient reports from later authors, particularly from Iamblichus, who appears to quote large extracts from it, without attribution, alongside extracts from extant works of Plato, in the second book of his work on Pythagoreanism.

Aresas of Lucania, and probably of Croton in Magna Graecia, was the head of the Pythagorean school, and the sixth head of the school in succession from Pythagoras himself. Diodorus of Aspendus was one of his students. He lived around the 4th or 5th century BCE.

The Italian School of Pre-Socratic philosophy refers to Ancient Greek philosophers in Italy or Magna Graecia in the 6th and 5th century BC. The doxographer Diogenes Laërtius divides pre Socratic philosophy into the Ionian and Italian School. According to classicist Jonathan Barnes, "Although the Italian 'school' was founded by émigrés from Ionia, it quickly took on a character of its own." According to classicist W. K. C. Guthrie, it contrasted with the "materialistic and purely rational Milesians."

Diotogenes was a Neopythagorean philosopher. He wrote a work On Piety, of which three fragments are preserved in Stobaeus, and another On Kingship, of which two considerable fragments are likewise extant in Stobaeus.

References

- Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Fant, Maureen B., "Private Life", Women's Life in Greece & Rome, 208. Chastity, archived from the original on 1 July 2016, retrieved 25 July 2017

- Plant, Ian (2004), Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome: An Anthology, Equinox, pp. 84–86, ISBN 1-904768-02-4

- Thesleff, Holger (1961), An Introduction to the Pythagorean Writings of the Hellenistic Period, Åbo akademi

- Waithe, Mary Ellen (1987), A History of Women Philosophers: Volume I: Ancient Women Philosophers, 600 BC - 500 AD, Springer, ISBN 90-247-3368-5

- Wider, Kathleen (1986), "Women Philosophers in the Ancient Greek World: Donning the Mantle", Hypatia, 1 (1): 21–62, doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1986.tb00521.x, S2CID 144952549