Córdoba, or sometimes Cordova, is a city in Andalusia, Spain, and the capital of the province of Córdoba. It is the third most populated municipality in Andalusia.

Islamic architecture comprises the architectural styles of buildings associated with Islam. It encompasses both secular and religious styles from the early history of Islam to the present day. The Islamic world encompasses a wide geographic area historically ranging from western Africa and Europe to eastern Asia. Certain commonalities are shared by Islamic architectural styles across all these regions, but over time different regions developed their own styles according to local materials and techniques, local dynasties and patrons, different regional centers of artistic production, and sometimes different religious affiliations.

Al-Andalus was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The term is used by modern historians for the former Islamic states in modern-day Gibraltar, Portugal, Spain, and Southern France. The name describes the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most of the peninsula and part of present-day southern France (Septimania) under Umayyad rule. These boundaries changed constantly through a series of conquests Western historiography has traditionally characterized as the Reconquista, eventually shrinking to the south and finally to the Emirate of Granada.

The maqāma is an (originally) Arabic prosimetric literary genre which alternates the Arabic rhymed prose known as Saj‘ with intervals of poetry in which rhetorical extravagance is conspicuous.

The Zirid dynasty, Banu Ziri, was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from what is now Algeria which ruled the central Maghreb from 972 to 1014 and Ifriqiya from 972 to 1148.

Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti was a 13th-century Iraqi-Arab painter and calligrapher, noted for being the scribe and illustrator of al-Hariri's Maqamat dated 1237 CE.

The Mahdia campaign of 1087 was a raid on the North African town of Mahdia by armed ships from the northern Italian maritime republics of Genoa and Pisa.

Madinat al-Zahra or Medina Azahara was a fortified palace-city on the western outskirts of Córdoba in present-day Spain. Its remains are a major archaeological site today. The city was built in the 10th century by Abd ar-Rahman III (912–961), a member of the Umayyad dynasty and the first caliph of Al-Andalus. It served as the capital of the Caliphate of Córdoba and its center of government.

Oleg Grabar was a French-born art historian and archeologist, who spent most of his career in the United States, as a leading figure in the field of Islamic art and architecture in the Western academe.

Pisa Cathedral is a medieval Roman Catholic cathedral dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, in the Piazza dei Miracoli in Pisa, Italy, the oldest of the three structures in the plaza followed by the Pisa Baptistry and the Campanile known as the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The cathedral is a notable example of Romanesque architecture, in particular the style known as Pisan Romanesque. Consecrated in 1118, it is the seat of the Archbishop of Pisa. Construction began in 1063 and was completed in 1092. Additional enlargements and a new facade were built in the 12th century and the roof was replaced after damage from a fire in 1595.

A multifoil arch, also known as a cusped arch, polylobed arch, or scalloped arch, is an arch characterized by multiple circular arcs or leaf shapes that are cut into its interior profile or intrados. The term foil comes from the old French word for "leaf." A specific number of foils is indicated by a prefix: trefoil (three), quatrefoil (four), cinquefoil (five), sexfoil (six), octofoil (eight). The term multifoil or scalloped is specifically used for arches with more than five foils. The multifoil arch is characteristic of Islamic art and architecture; particularly in the Moorish architecture of al-Andalus and North Africa and in Mughal architecture of the Indian subcontinent. Variants of the multifoil arch, such as the trefoil arch, are also common in other architectural traditions such as Gothic architecture.

Seljuk architecture comprises the building traditions that developed under the Seljuk dynasty, when it ruled most of the Middle East and Anatolia during the 11th to 13th centuries. The Great Seljuk Empire contributed significantly to the architecture of Iran and surrounding regions, introducing innovations such as the symmetrical four-iwan layout and the first widespread creation of state-sponsored madrasas. Their buildings were generally constructed in brick, with decoration created using brickwork, tiles, and carved stucco.

The Caliphate of Córdoba, also known as the Córdoban Caliphate, was an Arab Islamic state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from 929 to 1031. Its territory comprised Iberia and parts of North Africa, with its capital in Córdoba. It succeeded the Emirate of Córdoba upon the self-proclamation of Umayyad emir Abd ar-Rahman III as caliph in January 929. The period was characterized by an expansion of trade and culture, and saw the construction of masterpieces of al-Andalus architecture.

The city of Córdoba in al-Andalus, under the rule of Umayyad Caliph Hisham II al-Hakam, was besieged by Berbers from November 1009 until May 1013, with the city beyond the Roman walls completely destroyed. The siege, and the massacres and sacking that followed have been linked to the decline and end of Umayyad rule.

Ricardo Velázquez Bosco (1843–1923) was a Spanish architect, archaeologist and scholar.

Abu al-HakamMundhir ibn Sa'īd ibn Abd Allah ibn Abd ar-Rahman al-Ballūṭī was a Muslim legal expert and judiciary official in Al-Andalus. In addition to his legal career, he was also considered a prominent theologian, academic, linguist, poet and intellectual.

Abbasid architecture developed in the Abbasid Caliphate between 750 and 1227, primarily in its heartland of Mesopotamia . The great changes of the Abbasid era can be characterized as at the same time political, geo-political and cultural. The Abbasid period starts with the destruction of the Umayyad ruling family and its replacement by the Abbasids, and the position of power is shifted to the Mesopotamian area. As a result there was a corresponding displacement of the influence of classical and Byzantine artistic and cultural standards in favor of local Mesopotamian models as well as Persian. The Abbasids evolved distinctive styles of their own, particularly in decoration. This occurred mainly during the period corresponding with their power and prosperity between 750 and 932.

Umayyad architecture developed in the Umayyad Caliphate between 661 and 750, primarily in its heartlands of Syria and Palestine. It drew extensively on the architecture of older Middle Eastern and Mediterranean civilizations including the Sassanian Empire and Byzantine Empire, but introduced innovations in decoration and form. Under Umayyad patronage, Islamic architecture began to mature and acquire traditions of its own, such as the introduction of mihrabs to mosques, a trend towards aniconism in decoration, and a greater sense of scale and monumentality compared to previous Islamic buildings. The most important examples of Umayyad architecture are concentrated in the capital of Damascus and the Greater Syria region, including the Dome of the Rock, the Great Mosque of Damascus, and secular buildings such as the Mshatta Palace and Qusayr 'Amra.

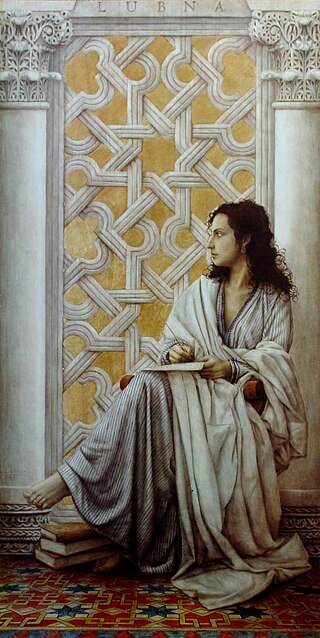

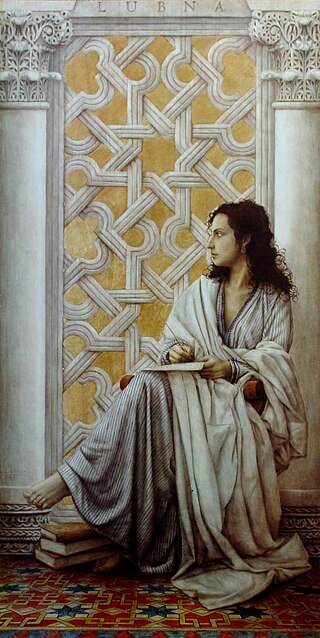

Lubna of Córdoba was an Andalusian intellectual, mathematician, and poet of the second half of the 10th century known for the quality of her writing and her excellence in the sciences. Lubna was born into slavery and raised within the Madīnat al-Zahrā palace. She then pursued a career within the palace as part of Al-Hakam II's team of copyists.

The Leyre Casket is one of the jewels of Hispano-Arab Islamic art. It is a casket or reliquary made of elephant ivory which was made in 1004/5 in the Caliphate of Cordoba.