Jericho is a city in the West Bank; it is the administrative seat of the Jericho Governorate of the State of Palestine. Jericho is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. In 2017, it had a population of 20,907.

Dame Kathleen Mary Kenyon, was a British archaeologist of Neolithic culture in the Fertile Crescent. She led excavations of Tell es-Sultan, the site of ancient Jericho, from 1952 to 1958, and has been called one of the most influential archaeologists of the 20th century. She was Principal of St Hugh's College, Oxford, from 1962 to 1973, having undertaken her own studies at Somerville College, Oxford.

The Neolithic or New Stone Age is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Europe, Asia and Africa. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts of the world. This "Neolithic package" included the introduction of farming, domestication of animals, and change from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one of settlement. The term 'Neolithic' was coined by Sir John Lubbock in 1865 as a refinement of the three-age system.

Natufian culture is a Late Epipaleolithic archaeological culture of the Neolithic prehistoric Levant in Western Asia, dating to around 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentary or semi-sedentary population even before the introduction of agriculture. Natufian communities may be the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region, which may have been the earliest in the world. Some evidence suggests deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture at Tell Abu Hureyra, the site of earliest evidence of agriculture in the world. The world's oldest known evidence of the production of bread-like foodstuff has been found at Shubayqa 1, a 14,400-year-old site in Jordan's northeastern desert, 4,000 years before the emergence of agriculture in Southwest Asia. In addition, the oldest known evidence of possible beer-brewing, dating to approximately 13,000 BP, was found in Raqefet Cave on Mount Carmel, although the beer-related residues may simply be a result of a spontaneous fermentation.

Neolithic architecture refers to structures encompassing housing and shelter from approximately 10,000 to 2,000 BC, the Neolithic period. In southwest Asia, Neolithic cultures appear soon after 10,000 BC, initially in the Levant and from there into the east and west. Early Neolithic structures and buildings can be found in southeast Anatolia, Syria, and Iraq by 8,000 BC with agriculture societies first appearing in southeast Europe by 6,500 BC, and central Europe by ca. 5,500 BC (of which the earliest cultural complexes include the Starčevo-Koros, Linearbandkeramic, and Vinča.

Göbekli Tepe is a Neolithic archaeological site in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. The settlement was inhabited from c. 9500 to at least 8000 BCE, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. It is famous for its large circular structures that contain massive stone pillars—the world's oldest known megaliths. Many of these pillars are decorated with anthropomorphic details, clothing, and sculptural reliefs of wild animals, providing archaeologists rare insights into prehistoric religion and the particular iconography of the period. The 15 m (50 ft)-high, 8 ha (20-acre) tell is densely covered with ancient domestic structures and other small buildings, quarries, and stone-cut cisterns from the Neolithic, as well as some traces of activity from later periods.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, in early Levantine and Anatolian Neolithic culture, dating to c. 12,000 – c. 10,800 years ago, that is, 10,000–8800 BCE. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and Upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to c. 10,800 – c. 8,500 years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the West Bank.

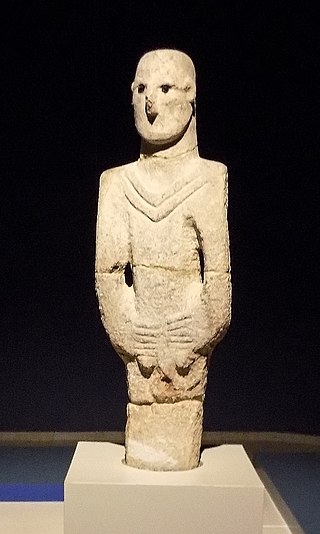

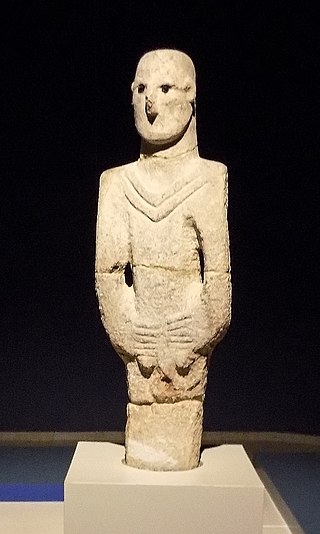

ʿAin Ghazal is a Neolithic archaeological site located in metropolitan Amman, Jordan, about 2 km north-west of Amman Civil Airport. The site is remarkable for being the place where the ʿAin Ghazal statues were found, which are among the oldest large-sized statues ever discovered.

In the archaeology of Southwest Asia, the Late Neolithic, also known as the Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period, following on from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and preceding the Chalcolithic. It is sometimes further divided into Pottery Neolithic A (PNA) and Pottery Neolithic B (PNB) phases.

Ghassulian refers to a culture and an archaeological stage dating to the Middle and Late Chalcolithic Period in the Southern Levant. Its type-site, Teleilat Ghassul, is located in the eastern Jordan Valley near the northern edge of the Dead Sea, in modern Jordan. It was excavated in 1929-1938 and in 1959–1960, by the Jesuits. Basil Hennessy dug at the site in 1967 and in 1975–1977, and Stephen Bourke in 1994–1999.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) represents the early Neolithic in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent, dating to c. 12,000 – c. 8,500 years ago,. It succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipalaeolithic Near East, as the domestication of plants and animals was in its formative stages, having possibly been induced by the Younger Dryas.

Tell Qaramel is a tell, or archaeological mound, located in the north of present-day Syria, 25 km north of Aleppo and about 65 km south of the Taurus mountains, adjacent to the river Quweiq that flows to Aleppo.

Tell Aswad, Su-uk-su or Shuksa, is a large prehistoric, neolithic tell, about 5 hectares (540,000 sq ft) in size, located around 48 kilometres (30 mi) from Damascus in Syria, on a tributary of the Barada River at the eastern end of the village of Jdeidet el Khass.

Tell es-Sultan, also known as Tel Jericho or Ancient Jericho, is an archaeological site and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the State of Palestine, in the city of Jericho, consisting of the remains of the oldest fortified city in the world.

White Ware or "Vaisselle Blanche", effectively a form of limestone plaster used to make vessels, is the first precursor to clay pottery developed in the Levant that appeared in the 9th millennium BC, during the pre-pottery (aceramic) neolithic period. It is not to be confused with "whiteware", which is both a term in the modern ceramic industry for most finer types of pottery for tableware and similar uses, and a term for specific historical types of earthenware made with clays giving an off-white body when fired.

The ʿAin Ghazal statues are a number of large-scale lime plaster and reed statues discovered at the archeological site of ʿAin Ghazal in Amman, Jordan, dating back to approximately 9000 years ago, from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period. A total of 15 statues and 15 busts were discovered in 1983 and 1985 in two underground caches, created about 200 years apart.

Köşk Höyük is a tell northeast of Bahçeli, near Kemerhisar in the modern Niğde Province of Turkey. It is located on the Bor Plateau, south of Mount Hasan near a spring.

The Urfa man, also known as the Balıklıgöl statue, is an ancient human shaped statue found during excavations in Balıklıgöl near Urfa, in the geographical area of Upper Mesopotamia, in the southeast of modern Turkey. It is dated c. 9000 BC to the period of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, and was considered as "the oldest naturalistic life-sized sculpture of a human". It is considered as contemporaneous with the sites of Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori.

Kharaysin is a Pre-Pottery Neolithic site (PPN) located in the village of Quneya, at the Zarqa River valley, Jordan. This site was discovered in 1984 by Hanbury-Tenison and colleagues during the Jerash Region Survey. The site was allocated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B because of the analysis of archaeological artefacts recovered on the surface.