Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the water, on ice (iceboat) or on land over a chosen course, which is often part of a larger plan of navigation.

Apparent wind is the wind experienced by a moving object.

A jibe (US) or gybe (Britain) is a sailing maneuver whereby a sailing vessel reaching downwind turns its stern through the wind, which then exerts its force from the opposite side of the vessel. Because the mainsail boom can swing across the cockpit quickly, jibes are potentially dangerous to person and rigging compared to tacking. Therefore, accidental jibes are to be avoided while the proper technique must be applied so as to control the maneuver. For square-rigged ships, this maneuver is called wearing ship.

Running rigging is the rigging of a sailing vessel that is used for raising, lowering, shaping and controlling the sails on a sailing vessel—as opposed to the standing rigging, which supports the mast and bowsprit. Running rigging varies between vessels that are rigged fore and aft and those that are square-rigged.

An iceboat is a recreational or competition sailing craft supported on metal runners for traveling over ice. One of the runners is steerable. Originally, such craft were boats with a support structure, riding on the runners and steered with a rear blade, as with a conventional rudder. As iceboats evolved, the structure became a frame with a seat or cockpit for the iceboat sailor, resting on runners. Steering was shifted to the front.

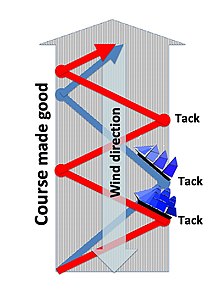

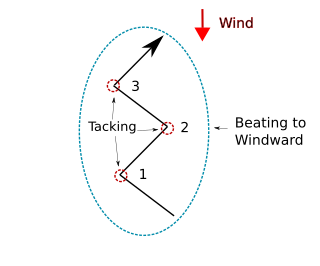

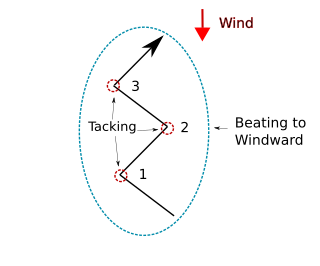

Tacking or coming about is a sailing maneuver by which a sailing craft, whose next destination is into the wind, turns its bow toward and through the wind so that the direction from which the wind blows changes from one side of the boat to the other, allowing progress in the desired direction. Sailing vessels are unable to sail higher than a certain angle towards the wind, so "beating to windward" in a zig-zag fashion with a series of tacking maneuvers, allows a vessel to sail towards a destination that is closer to the wind that the vessel can sail directly.

A fractional rig on a sailing vessel consists of a foresail, such as a jib or genoa sail, that does not reach all the way to the top of the mast.

Rounding-up is a phenomenon that occurs in sailing when the helmsman is no longer able to control the direction of the boat and it heads up into the wind, causing the boat to slow down, stall out, or tack. This occurs when the wind overpowers the ability of the rudder to maintain a straight course.

A wingsail, twin-skin sail or double skin sail is a variable-camber aerodynamic structure that is fitted to a marine vessel in place of conventional sails. Wingsails are analogous to airplane wings, except that they are designed to provide lift on either side to accommodate being on either tack. Whereas wings adjust camber with flaps, wingsails adjust camber with a flexible or jointed structure. Wingsails are typically mounted on an unstayed spar—often made of carbon fiber for lightness and strength. The geometry of wingsails provides more lift, and a better lift-to-drag ratio, than traditional sails. Wingsails are more complex and expensive than conventional sails.

Velocity made good, or VMG, is a term used in sailing, especially in yacht racing, indicating the speed of a sailboat towards the direction of the wind. The concept is useful because a sailboat cannot sail directly upwind, and thus often can not, or should not, sail directly to a mark to reach it as quickly as possible. It is also often less than optimal to sail directly downwind.

Wind-powered vehicles derive their power from sails, kites or rotors and ride on wheels—which may be linked to a wind-powered rotor—or runners. Whether powered by sail, kite or rotor, these vehicles share a common trait: As the vehicle increases in speed, the advancing airfoil encounters an increasing apparent wind at an angle of attack that is increasingly smaller. At the same time, such vehicles are subject to relatively low forward resistance, compared with traditional sailing craft. As a result, such vehicles are often capable of speeds exceeding that of the wind.

USA-17 is a sloop rigged racing trimaran built by the American sailing team BMW Oracle Racing to challenge for the 2010 America's Cup. Designed by VPLP Yacht Design with consultation from Franck Cammas and his Groupama multi-hull sailing team, BOR90 is very light for her size being constructed almost entirely out of carbon fiber and epoxy resin, and exhibits very high performance being able to sail at 2.0 to 2.5 times the true wind speed. From the actual performance of the boat during the 2010 America's Cup races, it can be seen that she could achieve a velocity made good upwind of over twice the wind speed and downwind of over 2.5 times the wind speed. She can apparently sail at 20 degrees off the apparent wind. The boat sails so fast downwind that the apparent wind she generates is only 5-6 degrees different from that when she is racing upwind; that is, the boat is always sailing upwind with respect to the apparent wind. An explanation of this phenomenon can be found in the article on sailing faster than the wind.

High-performance sailing is achieved with low forward surface resistance—encountered by catamarans, sailing hydrofoils, iceboats or land sailing craft—as the sailing craft obtains motive power with its sails or aerofoils at speeds that are often faster than the wind on both upwind and downwind points of sail. Faster-than-the-wind sailing means that the apparent wind angle experienced on the moving craft is always ahead of the sail. This has generated a new concept of sailing, called "apparent wind sailing", which entails a new skill set for its practitioners, including tacking on downwind points of sail.

A windmill ship, wind energy conversion system ship or wind energy harvester ship propels itself by use of a wind turbine to drive a propeller.

Forces on sails result from movement of air that interacts with sails and gives them motive power for sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and sail-powered land vehicles. Similar principles in a rotating frame of reference apply to windmill sails and wind turbine blades, which are also wind-driven. They are differentiated from forces on wings, and propeller blades, the actions of which are not adjusted to the wind. Kites also power certain sailing craft, but do not employ a mast to support the airfoil and are beyond the scope of this article.

SailTimer is a technology for sailboat navigation, which calculates optimal tacking angles, distances and times.

The B&R 23 is a sailing boat designed in the early 1990s. It has an ultralight construction with a very large sail plane. Typical crew is a helmsman and two deck hands in trapezes. The boat is predominantly used for racing.

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may be made from a combination of woven materials—including canvas or polyester cloth, laminated membranes or bonded filaments, usually in a three- or four-sided shape.

The lug sail, or lugsail, is a fore-and-aft, four-cornered sail that is suspended from a spar, called a yard. When raised, the sail area overlaps the mast. For "standing lug" rigs, the sail may remain on the same side of the mast on both the port and starboard tacks. For "dipping lug" rigs, the sail is lowered partially or totally to be brought around to the leeward side of the mast in order to optimize the efficiency of the sail on both tacks.

Wing and wing, Wing on wing, Goosewinging or Goosewinged, is a term used to define, in a fore-and-aft-rigged sailboat, the way to navigate sailing directly downwind, with the mainsail and the foresail extended outwards on opposite sides of the boat, forming a 180º angle, to maximize the projected area of sail exposed to the wind. The jib is held out by the clew with a whisker pole, to allow the capture of the maximum amount of wind on the chosen side, without being covered by the mainsail.