Related Research Articles

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others extend the definition to include substances like aerosols and gels. The term colloidal suspension refers unambiguously to the overall mixture. A colloid has a dispersed phase and a continuous phase. The dispersed phase particles have a diameter of approximately 1 nanometre to 1 micrometre.

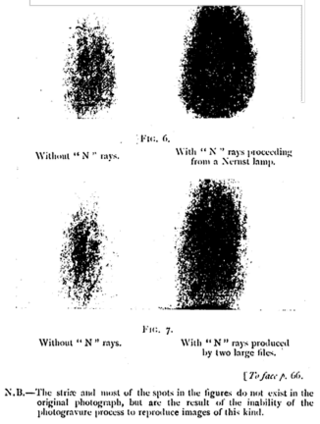

N-rays were a hypothesized form of radiation described by French physicist Prosper-René Blondlot in 1903. They were initially confirmed by others, but subsequently found to be illusory.

Pathological science is an area of research where "people are tricked into false results ... by subjective effects, wishful thinking or threshold interactions." The term was first used by Irving Langmuir, Nobel Prize-winning chemist, during a 1953 colloquium at the Knolls Research Laboratory. Langmuir said a pathological science is an area of research that simply will not "go away"—long after it was given up on as "false" by the majority of scientists in the field. He called pathological science "the science of things that aren't so."

Rheology is the study of the flow of matter, primarily in a fluid state, but also as "soft solids" or solids under conditions in which they respond with plastic flow rather than deforming elastically in response to an applied force. Rheology is a branch of physics, and it is the science that deals with the deformation and flow of materials, both solids and liquids.

Reproducibility, closely related to replicability and repeatability, is a major principle underpinning the scientific method. For the findings of a study to be reproducible means that results obtained by an experiment or an observational study or in a statistical analysis of a data set should be achieved again with a high degree of reliability when the study is replicated. There are different kinds of replication but typically replication studies involve different researchers using the same methodology. Only after one or several such successful replications should a result be recognized as scientific knowledge.

A non-Newtonian fluid is a fluid that does not follow Newton's law of viscosity, that is, it has variable viscosity dependent on stress. In particular, the viscosity of non-Newtonian fluids can change when subjected to force. Ketchup, for example, becomes runnier when shaken and is thus a non-Newtonian fluid. Many salt solutions and molten polymers are non-Newtonian fluids, as are many commonly found substances such as custard, toothpaste, starch suspensions, corn starch, paint, blood, melted butter, and shampoo.

Polyethylene terephthalate (or poly(ethylene terephthalate), PET, PETE, or the obsolete PETP or PET-P), is the most common thermoplastic polymer resin of the polyester family and is used in fibres for clothing, containers for liquids and foods, and thermoforming for manufacturing, and in combination with glass fibre for engineering resins.

Pitch is a viscoelastic polymer which can be natural or manufactured, derived from petroleum, coal tar, or plants. Pitch produced from petroleum may be called bitumen or asphalt, while plant-derived pitch, a resin, is known as rosin in its solid form. Tar is sometimes used interchangeably with pitch, but generally refers to a more liquid substance derived from coal production, including coal tar, or from plants, as in pine tar.

Boris Vladimirovich Derjaguin was a Soviet and Russian chemist. As a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, he laid the foundation of the modern science of colloids and surfaces. An epoch in the development of the physical chemistry of colloids and surfaces is associated with his name.

The Mpemba effect is the name given to the observation that a liquid which is initially hot can freeze faster than the same liquid which begins cold, under otherwise similar conditions. There is disagreement about its theoretical basis and the parameters required to produce the effect.

The Marangoni effect is the mass transfer along an interface between two phases due to a gradient of the surface tension. In the case of temperature dependence, this phenomenon may be called thermo-capillary convection.

Wet chemistry is a form of analytical chemistry that uses classical methods such as observation to analyze materials. It is called wet chemistry since most analyzing is done in the liquid phase. Wet chemistry is also called bench chemistry since many tests are performed at lab benches.

Denis L. Rousseau is an American scientist. He is currently professor and university chairman of the department of physiology and biophysics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water. Viscosity is defined scientifically as a force multiplied by a time divided by an area. Thus its SI units are newton-seconds per square meter, or pascal-seconds.

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a nearly constant volume independent of pressure. It is one of the four fundamental states of matter, and is the only state with a definite volume but no fixed shape.

The glass–liquid transition, or glass transition, is the gradual and reversible transition in amorphous materials from a hard and relatively brittle "glassy" state into a viscous or rubbery state as the temperature is increased. An amorphous solid that exhibits a glass transition is called a glass. The reverse transition, achieved by supercooling a viscous liquid into the glass state, is called vitrification.

Water is a polar inorganic compound that is at room temperature a tasteless and odorless liquid, which is nearly colorless apart from an inherent hint of blue. It is by far the most studied chemical compound and is described as the "universal solvent" and the "solvent of life". It is the most abundant substance on the surface of Earth and the only common substance to exist as a solid, liquid, and gas on Earth's surface. It is also the third most abundant molecule in the universe.

Cyclohexanedimethanol (CHDM) is a mixture of isomeric organic compounds with formula C6H10(CH2OH)2. It is a colorless low-melting solid used in the production of polyester resins. Commercial samples consist of a mixture of cis and trans isomers. It is a di-substituted derivative of cyclohexane and is classified as a diol, meaning that it has two OH functional groups. Commercial CHDM typically has a cis/trans ratio of 30:70.

Capillary breakup rheometry is an experimental technique used to assess the extensional rheological response of low viscous fluids. Unlike most shear and extensional rheometers, this technique does not involve active stretch or measurement of stress or strain but exploits only surface tension to create a uniaxial extensional flow. Hence, although it is common practice to use the name rheometer, capillary breakup techniques should be better addressed to as indexers.

Mechanics of gelation describes processes relevant to sol-gel process.

References

- 1 2 "Unnatural Water". Time magazine . December 19, 1969. Archived from the original on 27 December 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

Western scientists were frankly skeptical. Russian Chemists N. Fedyakin and Boris Deryagin claimed to have produced a mysterious new substance, a form of water so stable, it boiled only at about 1,000°F., or five times the boiling temperature of natural water. It did not evaporate. It did not freeze – though at −40°F., with little or no expansion, it hardened into a glassy substance, quite unlike ice.

- 1 2 "Polywater" . The New York Times . September 22, 1969. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

Water is so essential, so abundant, so simple in composition and so intensively studied over the centuries that it seems a most unlikely substance to provide a major scientific surprise. Nevertheless, this is precisely what has recently occurred. American chemists have confirmed that there is a form of water with properties quite different from that of the fluid everyone takes for granted. Polywater as this substance has been named is an organized aggregate or polymer of ordinary water molecules but it has very different properties from its ...

- ↑ "Doubts about Polywater". Time magazine . October 19, 1970. Archived from the original on 1 December 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

Challenged by critics to let impartial scientists analyze his polywater, Deryagin had turned over 25 tiny samples of the substance to investigators of the Soviet Academy of Sciences' Institute of Chemical Physics. The results, which were published in the journal, showed that Deryagin's polywater was badly contaminated by organic compounds, including lipids and phospholipids, which are ingredients of human perspiration.

- ↑ Butler, S. T. (September 17, 1973). "Polywater Debate Fizzles Out". The Sydney Morning Herald . Retrieved 1 May 2021– via Google News.

- ↑ Greenberg, Arthur (1 January 2009). "Chapter 8". Chemistry: Decade by Decade. New York, New York: Infobase Publishing (Facts on File imprint). p. 287. ISBN 978-1-4381-0978-7 . Retrieved 1 May 2021– via Google Books (Preview).

- ↑ Федякин (Fedyakin), Н.Н. (N.N.) (1962). "Изменение структуры воды при конденсации в капиллярах" [Changes in the structure of water during condensation in capillaries.]. Коллоидный Журнал (Kolloidnyi Zhurnal, Colloid Journal) (in Russian). 24: 497–501.

- ↑ Giaimo, Cara (21 September 2015). "Polywater, the Soviet Scientific Secret That Made the World Gulp". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ↑ Deryagin, B. V.; Fedyakin, N. N. (1962). "Special properties and viscosity of liquids condensed in capillaries". Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR Physics Chemistry. 147 (2): 808–811.

- ↑ "U.S. Begins Efforts To Exceed the USSR In Polywater Science. Pentagon Picks Firm to Study Water-Like Fluid That Boils At 400, Was Isolated in 1961". The Wall Street Journal . June 30, 1969. Retrieved 2010-12-24.

Good news The U.S. has apparently closed the polywater gap and the Pentagon is bankrolling efforts to push this country's polywater technology ahead of the ...

- ↑ Christian, P. A.; Berka, L. H. (June 1973). "How You Can Grow Your Own Polywater". Popular Science. pp. 105–107.

- ↑ Rousseau, Denis L.; Porto, Sergio P. S. (March 27, 1970). "Polywater: Polymer or Artifact?". Science. 167 (3926): 1715–1719. Bibcode:1970Sci...167.1715R. doi:10.1126/science.167.3926.1715. PMID 17729617. S2CID 37067352 . Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Rousseau, Denis L. (January 15, 1971). ""Polywater" and Sweat: Similarities between the Infrared Spectra". Science. 171 (3967): 170–172. Bibcode:1971Sci...171..170R. doi:10.1126/science.171.3967.170. PMID 5538826. S2CID 46032654 . Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ↑ Franks, Felix (1981). Polywater. The MIT Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-262-06073-6.

- ↑ Rousseau, Denis L. (January–February 1992). "Case Studies in Pathological Science". American Scientist . 80 (1): 54–63. Bibcode:1992AmSci..80...54R.

- 1 2 Henry H. Bauer. "'Pathological Science' is not Scientific Misconduct (nor is it pathological)". Hyle: International Journal for Philosophy of Chemistry . 8 (1): 5–20. The above paper cites this review from Eisenberg: David Eisenberg (September 1981). "A Scientific Gold Rush. (Book Reviews: Polywater)". Science . 213 (4512): 1104–1105. Bibcode:1981Sci...213.1104F. doi:10.1126/science.213.4512.1104. PMID 17741096.