Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated there were 283 million people with alcohol use disorders worldwide as of 2016. The term alcoholism was first coined in 1852, but alcoholism and alcoholic are stigmatizing and discourage seeking treatment, so clinical diagnostic terms such as alcohol use disorder or alcohol dependence are used instead.

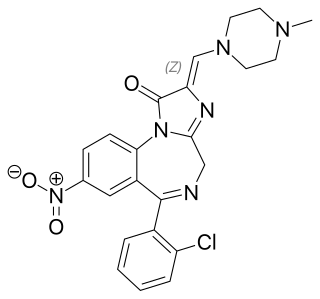

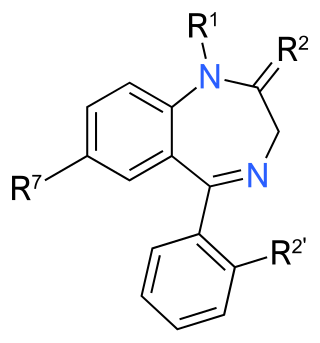

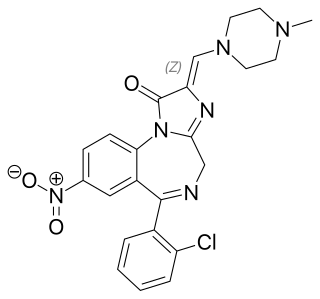

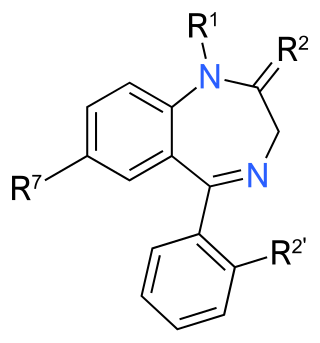

Benzodiazepines, colloquially called "benzos", are a class of depressant drugs whose core chemical structure is the fusion of a benzene ring and a diazepine ring. They are prescribed to treat conditions such as anxiety disorders, insomnia, and seizures. The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium), was discovered accidentally by Leo Sternbach in 1955 and was made available in 1960 by Hoffmann–La Roche, who soon followed with diazepam (Valium) in 1963. By 1977, benzodiazepines were the most prescribed medications globally; the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), among other factors, decreased rates of prescription, but they remain frequently used worldwide.

Diazepam, sold under the brand name Valium among others, is a medicine of the benzodiazepine family that acts as an anxiolytic. It is used to treat a range of conditions, including anxiety, seizures, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, muscle spasms, insomnia, and restless legs syndrome. It may also be used to cause memory loss during certain medical procedures. It can be taken orally, as a suppository inserted into the rectum, intramuscularly, intravenously or used as a nasal spray. When injected intravenously, effects begin in one to five minutes and last up to an hour. When taken by mouth, effects begin after 15 to 60 minutes.

Alprazolam, sold under the brand name Xanax among others, is a fast-acting, potent tranquilizer of moderate duration within the triazolobenzodiazepine group of chemicals called benzodiazepines. Alprazolam is most commonly used in management of anxiety disorders, specifically panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Other uses include the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea, together with other treatments. GAD improvement occurs generally within a week. Alprazolam is generally taken orally.

A sedative or tranquilliser is a substance that induces sedation by reducing irritability or excitement. They are CNS depressants and interact with brain activity causing its deceleration. Various kinds of sedatives can be distinguished, but the majority of them affect the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). In spite of the fact that each sedative acts in its own way, most produce relaxing effects by increasing GABA activity.

Drug withdrawal, drug withdrawal syndrome, or substance withdrawal syndrome, is the group of symptoms that occur upon the abrupt discontinuation or decrease in the intake of pharmaceutical or recreational drugs.

Triazolam, sold under the brand name Halcion among others, is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant tranquilizer of the triazolobenzodiazepine (TBZD) class, which are benzodiazepine (BZD) derivatives. It possesses pharmacological properties similar to those of other benzodiazepines, but it is generally only used as a sedative to treat severe insomnia. In addition to the hypnotic properties, triazolam's amnesic, anxiolytic, sedative, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant properties are pronounced as well.

Bromazepam, sold under many brand names, is a benzodiazepine. It is mainly an anti-anxiety agent with similar side effects to diazepam. In addition to being used to treat anxiety or panic states, bromazepam may be used as a premedicant prior to minor surgery. Bromazepam typically comes in doses of 3 mg and 6 mg tablets.

Oxazepam is a short-to-intermediate-acting benzodiazepine. Oxazepam is used for the treatment of anxiety and insomnia and in the control of symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Physical dependence is a physical condition caused by chronic use of a tolerance-forming drug, in which abrupt or gradual drug withdrawal causes unpleasant physical symptoms. Physical dependence can develop from low-dose therapeutic use of certain medications such as benzodiazepines, opioids, stimulants, antiepileptics and antidepressants, as well as the recreational misuse of drugs such as alcohol, opioids and benzodiazepines. The higher the dose used, the greater the duration of use, and the earlier age use began are predictive of worsened physical dependence and thus more severe withdrawal syndromes. Acute withdrawal syndromes can last days, weeks or months. Protracted withdrawal syndrome, also known as post-acute-withdrawal syndrome or "PAWS", is a low-grade continuation of some of the symptoms of acute withdrawal, typically in a remitting-relapsing pattern, often resulting in relapse and prolonged disability of a degree to preclude the possibility of lawful employment. Protracted withdrawal syndrome can last for months, years, or depending on individual factors, indefinitely. Protracted withdrawal syndrome is noted to be most often caused by benzodiazepines. To dispel the popular misassociation with addiction, physical dependence to medications is sometimes compared to dependence on insulin by persons with diabetes.

Substance dependence, also known as drug dependence, is a biopsychological situation whereby an individual's functionality is dependent on the necessitated re-consumption of a psychoactive substance because of an adaptive state that has developed within the individual from psychoactive substance consumption that results in the experience of withdrawal and that necessitates the re-consumption of the drug. A drug addiction, a distinct concept from substance dependence, is defined as compulsive, out-of-control drug use, despite negative consequences. An addictive drug is a drug which is both rewarding and reinforcing. ΔFosB, a gene transcription factor, is now known to be a critical component and common factor in the development of virtually all forms of behavioral and drug addictions, but not dependence.

Clorazepate, sold under the brand name Tranxene among others, is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative, hypnotic, and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. Clorazepate is an unusually long-lasting benzodiazepine and serves as a prodrug for the equally long-lasting desmethyldiazepam, which is rapidly produced as an active metabolite. Desmethyldiazepam is responsible for most of the therapeutic effects of clorazepate.

Loprazolam (triazulenone) marketed under many brand names is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. It is licensed and marketed for the short-term treatment of moderately-severe insomnia.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome is the cluster of signs and symptoms that may emerge when a person who has been taking benzodiazepines as prescribed develops a physical dependence on them and then reduces the dose or stops taking them without a safe taper schedule.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol use after a period of excessive use. Symptoms typically include anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, and a mild fever. More severe symptoms may include seizures, and delirium tremens (DTs); which can be fatal in untreated patients. Symptoms start at around 6 hours after last drink. Peak incidence of seizures occurs at 24-36 hours and peak incidence of delirium tremens is at 48-72 hours.

Benzodiazepine dependence defines a situation in which one has developed one or more of either tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, drug seeking behaviors, such as continued use despite harmful effects, and maladaptive pattern of substance use, according to the DSM-IV. In the case of benzodiazepine dependence, the continued use seems to be typically associated with the avoidance of unpleasant withdrawal reaction rather than with the pleasurable effects of the drug. Benzodiazepine dependence develops with long-term use, even at low therapeutic doses, often without the described drug seeking behavior and tolerance.

The effects of long-term benzodiazepine use include drug dependence as well as the possibility of adverse effects on cognitive function, physical health, and mental health. Long-term use is sometimes described as use not shorter than three months. Benzodiazepines are generally effective when used therapeutically in the short term, but even then the risk of dependency can be significantly high. There are significant physical, mental and social risks associated with the long-term use of benzodiazepines. Although anxiety can temporarily increase as a withdrawal symptom, there is evidence that a reduction or withdrawal from benzodiazepines can lead in the long run to a reduction of anxiety symptoms. Due to these increasing physical and mental symptoms from long-term use of benzodiazepines, slow withdrawal is recommended for long-term users. Not everyone, however, experiences problems with long-term use.

Panic disorder is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by reoccurring unexpected panic attacks. Panic attacks are sudden periods of intense fear that may include palpitations, sweating, shaking, shortness of breath, numbness, or a feeling that something terrible is going to happen. The maximum degree of symptoms occurs within minutes. There may be ongoing worries about having further attacks and avoidance of places where attacks have occurred in the past.

Kindling due to substance withdrawal is the neurological condition which results from repeated withdrawal episodes from sedative–hypnotic drugs such as alcohol and benzodiazepines.

Prescription drug addiction is the chronic, repeated use of a prescription drug in ways other than prescribed for, including using someone else’s prescription. A prescription drug is a pharmaceutical drug that may not be dispensed without a legal medical prescription. Drugs in this category are supervised due to their potential for misuse and substance use disorder. The classes of medications most commonly abused are opioids, central nervous system (CNS) depressants and central nervous stimulants. In particular, prescription opioid is most commonly abused in the form of prescription analgesics.