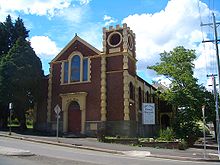

Christendom refers to Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion.

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system or life stance that embraces human reason, logic, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism, while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basis of morality and decision making.

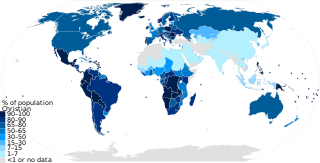

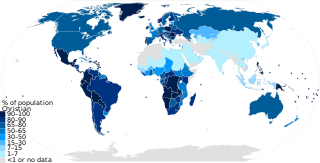

Irreligion is the absence or rejection of religious beliefs or practices. It encompasses a wide range of viewpoints drawn from various philosophical and intellectual perspectives, including atheism, agnosticism, skepticism, rationalism, and secularism. These perspectives can vary, with individuals who identify as irreligious holding a diverse array of specific beliefs about religion or its role in their lives.

In sociology, secularization is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism, irreligion, nor are they automatically anti-thetical to religion. Secularization has different connotations such as implying differentiation of secular from religious domains, the marginalization of religion in those domains, or it may also entail the transformation of religion as a result of its recharacterization.

Secularity, also the secular or secularness, is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself and fleshed out through Christian history into the modern era. In the medieval period there were even secular clergy. Furthermore, secular and religious entities were not separated in the medieval period, but coexisted and interacted naturally.

Nontheism or non-theism is a range of both religious and non-religious attitudes characterized by the absence of espoused belief in the existence of God or gods. Nontheism has generally been used to describe apathy or silence towards the subject of gods and differs from atheism, or active disbelief in any gods. It has been used as an umbrella term for summarizing various distinct and even mutually exclusive positions, such as agnosticism, ignosticism, ietsism, skepticism, pantheism, pandeism, transtheism, atheism, and apatheism. It is in use in the fields of Christian apologetics and general liberal theology.

State atheism or atheist state is the incorporation of hard atheism or non-theism into political regimes. It is considered the opposite of theocracy and may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments. To some extent, it is a religion-state relationship that is usually ideologically linked to irreligion and the promotion of irreligion or atheism. State atheism may refer to a government's promotion of anti-clericalism, which opposes religious institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, including the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen. In some instances, religious symbols and public practices that were once held by religions were replaced with secularized versions of them. State atheism in these cases is considered as not being politically neutral toward religion, and therefore it is often considered non-secular.

Jewish atheism refers to the atheism of people who are ethnically and culturally Jewish. Contrary to popular belief, the term "Jewish atheism" is not a contradiction because Jewish identity encompasses not only religious components, but also ethnic and cultural ones. Jewish law's emphasis on descent through the mother means that even religiously conservative Orthodox Jewish authorities would accept an atheist born to a Jewish mother as fully Jewish.

Criticism of atheism is criticism of the concepts, validity, or impact of atheism, including associated political and social implications. Criticisms include positions based on the history of science, philosophical and logical criticisms, findings in both the natural and social sciences, theistic apologetic arguments, arguments pertaining to ethics and morality, the effects of atheism on the individual, or the assumptions that underpin atheism.

Some movements or sects within traditionally monotheistic or polytheistic religions recognize that it is possible to practice religious faith, spirituality and adherence to tenets without a belief in deities. People with what would be considered religious or spiritual belief in a supernatural controlling power are defined by some as adherents to a religion; the argument that atheism is a religion has been described as a contradiction in terms.

Death of God theology refers to a range of ideas by various theologians and philosophers that try to account for the rise of secularity and abandonment of traditional beliefs in God. They posit that God has either ceased to exist or in some way accounted for such a belief.

Gabriel Vahanian was a French Protestant Christian theologian who was most remembered for his pioneering work in the theology of the "death of God" movement within academic circles in the 1960s, and who taught for 26 years in the U.S. before finishing a prestigious career in Strasbourg, France.

Thomas Jonathan Jackson Altizer was an American university professor, religious scholar, and theologian, noted for his incorporation of Death of God theology and Hegelian dialectical philosophy into his body of work. He regarded his philosophical theology as also being grounded in the works of William Blake and considered his theology to have come into its own with his extended study of Blake's radical visionary thinking: The New Apocalypse: The Radical Christian Vision of William Blake (1967); indeed he regarded himself as the first and only fully Blakean theologian.

Secular theology is a term applied to theological positions influenced by humanism and secularism, rejecting supernatural metaphysical positions related to the nature of God. Secular theology can accommodate a belief in God, like many nature religions, but as residing in this world and not separately from it.

Christian atheism embraces the teachings, narratives, symbols, practices, or communities associated with Christianity without accepting the literal existence of God.

An infidel is a person who is accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or irreligious people.

Irreligion in France has a long history and a large demographic constitution, with the advancement of atheism and the deprecation of theistic religion dating back as far as the French Revolution. In 2015, according to estimates, at least 29% of the country's population identifies as atheists and 63% identifies as non-religious.

China has the world's largest irreligious population, and the Chinese government and the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are officially atheist. Despite limitations on certain forms of religious expression and assembly, religion is not banned, and religious freedom is nominally protected under the Chinese constitution. Among the general Chinese population, there are a wide variety of religious practices. The Chinese government's attitude to religion is one of skepticism and non-promotion.

Philip Joseph Zuckerman is a sociologist and professor of sociology and secular studies at Pitzer College in Claremont, California. He specializes in the sociology of substantial secularity and is the author of several books, including What It Means to Be Moral: Why Religion Is Not Necessary for Living an Ethical Life (2019).