Related Research Articles

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of how and why humans grow, change, and adapt across the course of their lives. Originally concerned with infants and children, the field has expanded to include adolescence, adult development, aging, and the entire lifespan. Developmental psychologists aim to explain how thinking, feeling, and behaviors change throughout life. This field examines change across three major dimensions, which are physical development, cognitive development, and social emotional development. Within these three dimensions are a broad range of topics including motor skills, executive functions, moral understanding, language acquisition, social change, personality, emotional development, self-concept, and identity formation.

Educational psychology is the branch of psychology concerned with the scientific study of human learning. The study of learning processes, from both cognitive and behavioral perspectives, allows researchers to understand individual differences in intelligence, cognitive development, affect, motivation, self-regulation, and self-concept, as well as their role in learning. The field of educational psychology relies heavily on quantitative methods, including testing and measurement, to enhance educational activities related to instructional design, classroom management, and assessment, which serve to facilitate learning processes in various educational settings across the lifespan.

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to conscious cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, and deliberation. But other mental processes, like considering an idea, memory, or imagination, are also often included. These processes can happen internally independent of the sensory organs, unlike perception. But when understood in the widest sense, any mental event may be understood as a form of thinking, including perception and unconscious mental processes. In a slightly different sense, the term thought refers not to the mental processes themselves but to mental states or systems of ideas brought about by these processes.

Jean William Fritz Piaget was a Swiss psychologist known for his work on child development. Piaget's theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called "genetic epistemology".

Piaget's theory of cognitive development is a comprehensive theory about the nature and development of human intelligence. It was originated by the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). The theory deals with the nature of knowledge itself and how humans gradually come to acquire, construct, and use it. Piaget's theory is mainly known as a developmental stage theory.

In psychology, developmental stage theories are theories that divide psychological development into distinct stages which are characterized by qualitative differences in behavior.

Cognitive development is a field of study in neuroscience and psychology focusing on a child's development in terms of information processing, conceptual resources, perceptual skill, language learning, and other aspects of the developed adult brain and cognitive psychology. Qualitative differences between how a child processes their waking experience and how an adult processes their waking experience are acknowledged. Cognitive development is defined as the emergence of the ability to consciously cognize, understand, and articulate their understanding in adult terms. Cognitive development is how a person perceives, thinks, and gains understanding of their world through the relations of genetic and learning factors. There are four stages to cognitive information development. They are, reasoning, intelligence, language, and memory. These stages start when the baby is about 18 months old, they play with toys, listen to their parents speak, they watch tv, anything that catches their attention helps build their cognitive development.

In psychology, centration is the tendency to focus on one salient aspect of a situation and neglect other, possibly relevant aspects. Introduced by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget through his cognitive-developmental stage theory, centration is a behaviour often demonstrated in the preoperational stage. Piaget claimed that egocentrism, a common element responsible for preoperational children's unsystematic thinking, was causal to centration. Research on centration has primarily been made by Piaget, shown through his conservation tasks, while contemporary researchers have expanded on his ideas.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to thought (thinking):

The model of hierarchical complexity (MHC) is a framework for scoring how complex a behavior is, such as verbal reasoning or other cognitive tasks. It quantifies the order of hierarchical complexity of a task based on mathematical principles of how the information is organized, in terms of information science. This model was developed by Michael Commons and Francis Richards in the early 1980s.

Positive adult development is a subfield of developmental psychology that studies positive development during adulthood. It is one of four major forms of adult developmental study that can be identified, according to Michael Commons; the other three forms are directionless change, stasis, and decline. Commons divided positive adult developmental processes into at least six areas of study: hierarchical complexity, knowledge, experience, expertise, wisdom, and spirituality.

Michael Lamport Commons is a theoretical behavioral scientist and a complex systems scientist. He developed the model of hierarchical complexity.

Domain-general learning theories of development suggest that humans are born with mechanisms in the brain that exist to support and guide learning on a broad level, regardless of the type of information being learned. Domain-general learning theories also recognize that although learning different types of new information may be processed in the same way and in the same areas of the brain, different domains also function interdependently. Because these generalized domains work together, skills developed from one learned activity may translate into benefits with skills not yet learned. Another facet of domain-general learning theories is that knowledge within domains is cumulative, and builds under these domains over time to contribute to our greater knowledge structure. Psychologists whose theories align with domain-general framework include developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, who theorized that people develop a global knowledge structure which contains cohesive, whole knowledge internalized from experience, and psychologist Charles Spearman, whose work led to a theory on the existence of a single factor accounting for all general cognitive ability.

Infant cognitive development is the first stage of human cognitive development, in the youngest children. The academic field of infant cognitive development studies of how psychological processes involved in thinking and knowing develop in young children. Information is acquired in a number of ways including through sight, sound, touch, taste, smell and language, all of which require processing by our cognitive system.

The psychology of reasoning is the study of how people reason, often broadly defined as the process of drawing conclusions to inform how people solve problems and make decisions. It overlaps with psychology, philosophy, linguistics, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, logic, and probability theory.

Neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development criticize and build upon Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development.

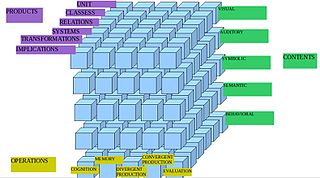

Mental operations are operations that affect mental contents. Initially, operations of reasoning have been the object of logic alone. Pierre Janet was one of the first to use the concept in psychology. Mental operations have been investigated at a developmental level by Jean Piaget, and from a psychometric perspective by J. P. Guilford. There is also a cognitive approach to the subject, as well as a systems view of it.

The constructive developmental framework (CDF) is a theoretical framework for epistemological and psychological assessment of adults. The framework is based on empirical developmental research showing that an individual's perception of reality is an actively constructed "world of their own", unique to them and which they continue to develop over their lifespan.

Horizontal and vertical décalage are terms coined by developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, which he used to describe the four stages in Piaget's theory of cognitive development: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operations, and formal operations. According to Piaget, horizontal and vertical décalage generally occur during the concrete operations stage of development.

Juan Pascual-Leone is a developmental psychologist and founder of the neo-Piagetian approach to cognitive development. He introduced this term into the literature and put forward key predictions about developmental growth of mental attention and working memory.

References

- 1 2 Berger, Kathleen Stassen (2014). Invitation to the Life Span (Second ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. pp. 399–401. ISBN 978-1-4292-8352-6.

- ↑ Griffin, James; Gooding, Sarah; Semesky, Michael; Farmer, Brittany; Mannchen, Garrett; Sinnott, Jan (August 2009). "Four brief studies of relations between postformal thought and non-cognitive factors: personality, concepts of God, political opinions, and social attitudes". Journal of Adult Development. 16 (3): 173–182 (173). doi:10.1007/s10804-009-9056-0. S2CID 143492595.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sinnott, Jan D. (1998). The development of logic in adulthood: postformal thought and its applications. New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2911-5. ISBN 978-1-4757-2911-5. OCLC 851775294.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Basseches, Michael. (1984). Dialectical thinking and adult development . Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub. Corp. ISBN 0-89391-017-1. OCLC 10532903.

- ↑ Arlin, Patricia K. (1975). "Cognitive development in adulthood: A fifth stage?". Developmental Psychology . 11 (5): 602–606. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.11.5.602. ISSN 0012-1649.

- ↑ Riegel, Klaus F. (1975). "Toward a dialectical theory of development". Human Development . 18 (1–2): 50–64. doi:10.1159/000271475. ISSN 1423-0054.

- ↑ Marchand, Helena (2001). "Some reflections on post-formal thought". The Genetic Epistemologist. 29 (3): 2–9.

- ↑ Kallio, Eeva; Helkama, Klaus (March 1991). "Formal operations and postformal reasoning: A replication". Scandinavian Journal of Psychology . 32 (1): 18–21. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.1991.tb00848.x.

- ↑ Kallio, Eeva (July 1995). "Systematic reasoning: Formal or postformal cognition?". Journal of Adult Development. 2 (3): 187–192. doi:10.1007/BF02265716. S2CID 145091949.

- ↑ Kramer, Deirdre A. (1983). "Post-formal operations? A need for further conceptualization". Human Development . 26 (2): 91–105. doi:10.1159/000272873.

- ↑ Kallio, Eeva (December 2011). "Integrative thinking is the key: an evaluation of current research into the development of adult thinking". Theory & Psychology . 21 (6): 785–801. doi:10.1177/0959354310388344. S2CID 143140546.

- ↑ Labouvie-Vief, Gisela (1992). "A Neo-Piagetian perspective on adult cognitive development". Intellectual development. Sternberg, Robert J., Berg, Cynthia A. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 0-521-39456-2. OCLC 23766221.

- ↑ Kramer, Deirdre A.; Woodruff, Diana S. (1986). "Relativistic and dialectical thought in three adult age-groups". Human Development . 29 (5): 280–290. doi:10.1159/000273064. ISSN 1423-0054.

- ↑ Reich, K.H.; Ozer, F (1990). "Konkret-operatorisches, formal-operatorisches and komplementaeres Denken, Begriffs- und Theorienentwicklung: Welche Beziehungen?". Unpublished Manuscript, University of Fribourg, Switzerland.