Related Research Articles

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups.

International relations (IR) are the interactions among sovereign states. The scientific study of those interactions is called international studies, international politics, or international affairs. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities among states—such as war, diplomacy, trade, and foreign policy—as well as relations with and among other international actors, such as intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), international legal bodies, and multinational corporations (MNCs). There are several schools of thought within IR, of which the most prominent are realism, liberalism, and constructivism.

International relations theory is the study of international relations (IR) from a theoretical perspective. It seeks to explain behaviors and outcomes in international politics. The four most prominent schools of thought are realism, liberalism, constructivism, and rational choice. Whereas realism and liberalism make broad and specific predictions about international relations, constructivism and rational choice are methodological approaches that focus on certain types of social explanation for phenomena.

Bassam Tibi, is a Syrian-born German political scientist and professor of international relations specializing in Islamic studies and Middle Eastern studies. He was born in 1944 in Damascus, Syria to an aristocratic family, and moved to West Germany in 1962, where he later became a naturalized citizen in 1976.

Power politics is a theory of power in international relations which contends that distributions of power and national interests, or changes to those distributions, are fundamental causes of war and of system stability.

Hans Joachim Morgenthau was a German-American jurist and political scientist who was one of the major 20th-century figures in the study of international relations. Morgenthau's works belong to the tradition of realism in international relations theory; he is usually considered among the most influential realists of the post-World War II period. Morgenthau made landmark contributions to international relations theory and the study of international law. His Politics Among Nations, first published in 1948, went through five editions during his lifetime and was widely adopted as a textbook in U.S. universities. While Morgenthau emphasized the centrality of power and "the national interest," the subtitle of Politics Among Nations—"the struggle for power and peace"—indicates his concern not only with the struggle for power but also with the ways in which it is limited by ethical and legal norms.

Hedley Norman Bull was Professor of International Relations at the Australian National University, the London School of Economics and the University of Oxford until his death from cancer in 1985. He was Montague Burton Professor of International Relations at Oxford from 1977 to 1985, and died there.

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats to, and breaches of peace. Collective security is more ambitious than systems of alliance security or collective defense in that it seeks to encompass the totality of states within a region or indeed globally, and to address a wide range of possible threats. While collective security is an idea with a long history, its implementation in practice has proved problematic. Several prerequisites have to be met for it to have a chance of working. It is the theory or practice of states pledging to defend one another in order to deter aggression or to target a transgressor if international order has been breached.

The Twenty Years' Crisis: 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations is a book on international relations written by E. H. Carr. The book was written in the 1930s shortly before the outbreak of World War II in Europe and the first edition was published in September 1939, shortly after the war's outbreak; a second edition was published in 1945. In the revised edition, Carr did not "re-write every passage which had been in someway modified by the subsequent course of events", but rather decided "to modify a few sentences" and undertake other small efforts to improve the clarity of the work.

Idealism in the foreign policy context holds that a nation-state should make its internal political philosophy the goal of its conduct and rhetoric in international affairs. For example, an idealist might believe that ending poverty at home should be coupled with tackling poverty abroad. Both within and outside of the United States, American president Woodrow Wilson is widely considered an early advocate of idealism and codifier of its practical meaning; specific actions cited include the issuing of the famous "Fourteen Points".

Realism is one of the dominant schools of thought in international relations theory, theoretically formalizing the Realpolitik statesmanship of early modern Europe. Although a highly diverse body of thought, it is unified by the belief that world politics is always and necessarily a field of conflict among actors pursuing wealth and power. The theories of realism are contrasted by the cooperative ideals of liberalism in international relations.

The Westphalian system, also known as Westphalian sovereignty, is a principle in international law that each state has exclusive sovereignty over its territory. The principle developed in Europe after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, based on the state theory of Jean Bodin and the natural law teachings of Hugo Grotius. It underlies the modern international system of sovereign states and is enshrined in the United Nations Charter, which states that "nothing ... shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state."

The English School of international relations theory maintains that there is a 'society of states' at the international level, despite the condition of anarchy. The English school stands for the conviction that ideas, rather than simply material capabilities, shape the conduct of international politics, and therefore deserve analysis and critique. In this sense it is similar to constructivism, though the English School has its roots more in world history, international law and political theory, and is more open to normative approaches than is generally the case with constructivism.

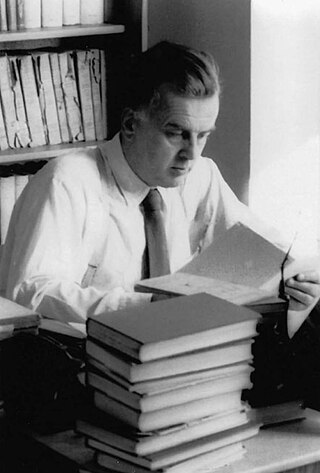

Robert James Martin Wight was one of the foremost British scholars of international relations in the twentieth century. He was the author of Power Politics, as well as the seminal essay "Why Is There No International Theory?". He was a teacher of some renown at both the London School of Economics and the University of Sussex, where he served as the founding Dean of European Studies.

Andrew Hurrell, FBA is a British professor emeritus. He was the Montague Burton Professor of International Relations and a Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. He was educated at Gresham's School, Holt, Norfolk. He was previously a Faculty Fellow in International Relations at Nuffield College, Oxford. He is Director of the Centre for International Studies at the Department of Politics and International Relations of the University of Oxford.

Neo-medievalism is a term with a long history that has acquired specific technical senses in two branches of scholarship. In political theory about modern international relations, where the term is originally associated with Hedley Bull, it sees the political order of a globalized world as analogous to high-medieval Europe, where neither states nor the Church, nor other territorial powers, exercised full sovereignty, but instead participated in complex, overlapping and incomplete sovereignties.

The British Committee on the Theory of International Politics was a group of scholars created in 1959 under the chairmanship of the Cambridge historian Herbert Butterfield, with financial aid from the Rockefeller Foundation, that met periodically in Cambridge, Oxford, London and Brighton to discuss the principal problems and a range of aspects of the theory and history of international relations. The Committee developed a study of international society and the nature of world politics, which have had an important impact that continues in the present day.

Stephen Gill, FRSC is Distinguished Research Professor of Political Science at York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. He is known for his work in International Relations and Global Political Economy and has published, among others, Power and Resistance in the New World Order, Power, Production and Social Reproduction, Gramsci, Historical Materialism and International Relations (1993), American Hegemony and the Trilateral Commission (1990) and The Global Political Economy: Perspectives, Problems and Policies.

Anarchy is a society without a government.

State collapse is a sudden dissolution of a sovereign state. It is often used to describe extreme situations in which state institutions dissolve rapidly.

References

- ↑ Ian Hall, The International Thought of Martin Wight, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 97.

- ↑ Ian Hall, The international thought of Martin Wight, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power Politics, Pelican, 1978, p. 9.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, p. 23.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, p. 37.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, p. 41-42.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, chapter three.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, p 86.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, p. 94.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, p. 107.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, pp. 110-12.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, pp. 102-5.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, p. 113.

- ↑ Martin Wight, Power politics, Pelican, 1978, chapter 11.

- ↑ Brian Porter, review of Ian Hall, The International Thought of Martin Wight, in International Affairs , 83:4, 2007.

- ↑ 'The enigma of Martin Wight', Review of International Studies , 1981

- ↑ F. P. King, "The American Historical Review", volume 84/3, 1/6/1979, pp. 710-711.