Evolution of hairlessness

The general hairlessness of humans in comparison to related species may be due to loss of functionality in the pseudogene KRTHAP1 (which helps produce keratin) in the human lineage about 240,000 years ago. [1] On an individual basis, mutations in the gene HR can lead to complete hair loss, though this is not typical in humans. [2] Humans may also lose their hair as a result of hormonal imbalance due to drugs or pregnancy. [3]

In order to comprehend why humans have significantly less body hair than other primates, one must understand that mammalian body hair is not merely an aesthetic characteristic; it protects the skin from wounds, bites, heat, cold, and UV radiation. [4] Additionally, it can be used as a communication tool and as a camouflage. [5]

The first member of the genus Homo to be hairless was Homo erectus , originating about 1.6 million years ago. [6] The dissipation of body heat remains the most widely accepted evolutionary explanation for the loss of body hair in early members of the genus Homo, the surviving member of which is modern humans. [7] [8] [9] Less hair, and an increase in sweat glands, made it easier for their bodies to cool when they moved from living in shady forest to open savanna. This change in environment also resulted in a change in diet, from largely vegetarian to hunting. Pursuing game on the savanna also increased the need for regulation of body heat. [10] [11]

Anthropologist and paleo-biologist Nina Jablonski posits that the ability to dissipate excess body heat through eccrine sweating helped make possible the dramatic enlargement of the brain, the most temperature-sensitive human organ. [12] Thus the loss of fur was also a factor in further adaptations, both physical and behavioral, that differentiated humans from other primates. Some of these changes are thought to be the result of sexual selection. By selecting more hairless mates, humans accelerated changes initiated by natural selection. Sexual selection may also account for the remaining human hair in the pubic area and armpits, which are sites for pheromones, while hair on the head continued to provide protection from the sun. [13] Anatomically modern humans, whose traits include hairlessness, evolved 260,000 to 350,000 years ago. [14]

Phenotypic changes

Humans are the only primate species that have undergone significant hair loss and of the approximately 5000 extant species of mammal, only a handful are effectively hairless. This list includes elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, walruses, some species of pigs, whales and other cetaceans, and naked mole rats. [5] Most mammals have light skin that is covered by fur, and biologists believe that early human ancestors started out this way also. Dark skin probably evolved after humans lost their body fur, because the naked skin was vulnerable to the strong UV radiation as explained in the Out of Africa hypothesis. Therefore, evidence of the time when human skin darkened has been used to date the loss of human body hair, assuming that the dark skin was needed after the fur was gone.

With the loss of fur, darker, high-melanin skin evolved as a protection from ultraviolet radiation damage. [15] As humans migrated outside of the tropics, varying degrees of depigmentation evolved in order to permit UVB-induced synthesis of previtamin D3. [16] [17] The relative lightness of female compared to male skin in a given population may be due to the greater need for women to produce more vitamin D during lactation. [18]

The sweat glands in humans could have evolved to spread from the hands and feet as the body hair changed, or the hair change could have occurred to facilitate sweating. Horses and humans are two of the few animals capable of sweating on most of their body, yet horses are larger and still have fully developed fur. In humans, the skin hairs lie flat in hot conditions, as the arrector pili muscles relax, preventing heat from being trapped by a layer of still air between the hairs, and increasing heat loss by convection.

Sexual selection hypothesis

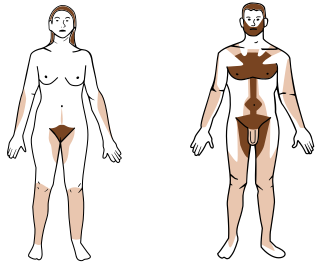

Another hypothesis for the thick body hair on humans proposes that Fisherian runaway sexual selection played a role (as well as in the selection of long head hair), (see terminal and vellus hair), as well as a much larger role of testosterone in men. Sexual selection is the only theory thus far that explains the sexual dimorphism seen in the hair patterns of men and women. On average, men have more body hair than women. Males have more terminal hair, especially on the face, chest, abdomen, and back, and females have more vellus hair, which is less visible. The halting of hair development at a juvenile stage, vellus hair, would also be consistent with the neoteny evident in humans, especially in females, and thus they could have occurred at the same time. [19] This theory, however, has significant holdings in today's cultural norms. There is no evidence that sexual selection would proceed to such a drastic extent over a million years ago when a full, lush coat of hair would most likely indicate health and would therefore be more likely to be selected for, not against.

Water-dwelling hypothesis

The aquatic ape hypothesis (AAH) includes hair loss as one of several characteristics of modern humans that could indicate adaptations to an aquatic environment. Serious consideration may be given by contemporary anthropologists to some hypotheses related to AAH, but hair loss is not one of them. [20]

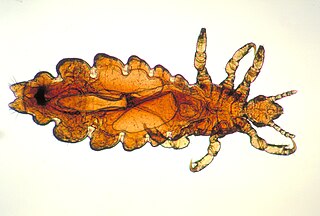

Parasite hypothesis

A divergent explanation of humans' relative hairlessness holds that ectoparasites (such as ticks) residing in fur became problematic as humans became hunters living in larger groups with a "home base". [21] [22] Nakedness would also make the lack of parasites apparent to prospective mates. [23] However, this theory is inconsistent with the abundance of parasites that continue to exist in the remaining patches of human hair. [24]

The "ectoparasite" explanation of modern human nakedness is based on the principle that a hairless primate would harbor fewer parasites. When our ancestors adopted group-dwelling social arrangements roughly 1.8 mya, ectoparasite loads increased dramatically. Early humans became the only one of the 193 primate species to have fleas, which can be attributed to the close living arrangements of large groups of individuals. While primate species have communal sleeping arrangements, these groups are always on the move and thus are less likely to harbor ectoparasites.

It was expected that dating the split of the ancestral human louse into two species, the head louse and the pubic louse, would date the loss of body hair in human ancestors. However, it turned out that the human pubic louse does not descend from the ancestral human louse, but from the gorilla louse, diverging 3.3 million years ago. This suggests that humans had lost body hair (but retained head hair) and developed thick pubic hair prior to this date, were living in or close to the forest where gorillas lived, and acquired pubic lice from butchering gorillas or sleeping in their nests. [25] [26] The evolution of the body louse from the head louse, on the other hand, places the date of clothing much later, some 100,000 years ago. [27] [28]

Fire hypothesis

Another hypothesis is that humans' use of fire caused or initiated the reduction in human hair. [29]

Childrearing hypothesis

Another view is proposed by James Giles, who attempts to explain hairlessness as evolved from the relationship between mother and child, and as a consequence of bipedalism. Giles also connects romantic love to hairlessness. [30] [31]

The last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees was only partially bipedal, often using their front legs for locomotion. Other primate mothers do not need to carry their young because there is fur for them to cling to, but the loss of fur encouraged full bipedalism, allowing the mothers to carry their babies with one or both hands. [32] The combination of hairlessness and upright posture may also explain the enlargement of the female breasts as a sexual signal. [9] Giles' theory is that the loss of fur also promoted mother-child attachment based upon the pleasure of skin-to-skin contact. This may explain the more extensive hairlessness of female humans and infants compared to adult males. Nakedness also affects sexual relationships as well, the duration of human intercourse being many times the duration of any other primates. [24]