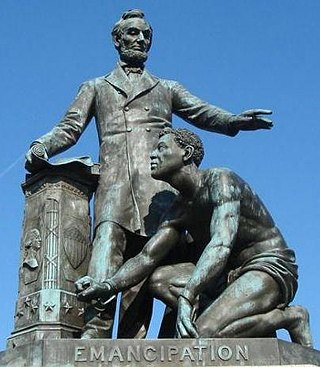

Abraham Lincoln was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman, who served as the 16th president of the United States, from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the United States through the American Civil War, defending the nation as a constitutional union, defeating the insurgent Confederacy, playing a major role in the abolition of slavery, expanding the power of the federal government, and modernizing the U.S. economy.

The 1860 United States presidential election was the 19th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 6, 1860. In a four-way contest, the Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin won a national popular plurality, a popular majority in the North where states already had abolished slavery, and a national electoral majority comprising only Northern electoral votes. Lincoln's election thus served as the main catalyst of the states that would become the Confederacy seceding from the Union. This marked the first time that a Republican was elected president. It was also the first presidential election in which both major party candidates were registered in the same home state; the others have been in 1904, 1920, 1940, 1944, and 2016.

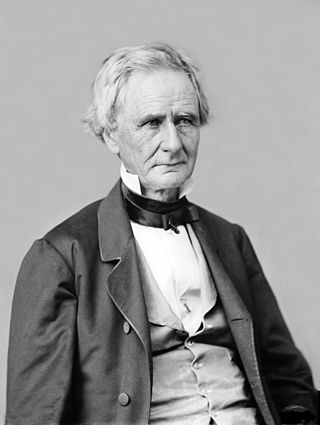

William Henry Seward was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined opponent of the spread of slavery in the years leading up to the American Civil War, he was a prominent figure in the Republican Party in its formative years, and was praised for his work on behalf of the Union as Secretary of State during the Civil War. He also negotiated the treaty for the United States to purchase the Alaska Territory.

Simon Cameron was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the American Civil War.

Historians who address the origins of the American Civil War agree that the preservation of the institution of slavery was the principal aim of the 11 Southern states that declared their secession from the United States and united to form the Confederate States of America. However, while historians in the 21st century agree on the centrality of the conflict over slavery—it was not just "a cause" of the war but "the cause" according to Civil War historian Chris Mackowski—they disagree sharply on which aspects of this conflict were most important, and on the North’s reasons for refusing to allow the Southern states to secede. Proponents of the pseudo-historical Lost Cause ideology have denied that slavery was the principal cause of the secession, a view that has been disproven by the overwhelming historical evidence against it, notably the seceding states' own secession documents.

The Corwin Amendment is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that has never been adopted, but owing to the absence of a ratification deadline, could still be adopted by the state legislatures. It would shield slavery within the states from the federal constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress. Although the Corwin Amendment does not explicitly use the word slavery, it was designed specifically to protect slavery from federal power. The outgoing 36th United States Congress proposed the Corwin Amendment on March 2, 1861, shortly before the outbreak of the American Civil War, with the intent of preventing that war and preserving the Union. It passed Congress but was not ratified by the requisite number of state legislatures.

The Constitutional Union Party was a United States third party active during the 1860 elections. It consisted of conservative former Whigs, largely from the Southern United States, who wanted to avoid secession over the slavery issue and refused to join either the Republican Party or the Democratic Party. The Constitutional Union Party campaigned on a simple platform "to recognize no political principle other than the Constitution of the country, the Union of the states, and the Enforcement of the Laws".

The 1860 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met May 16–18 in Chicago, Illinois. It was held to nominate the Republican Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1860 election. The convention selected former representative Abraham Lincoln of Illinois for president and Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine for vice president.

The Crittenden Compromise was an unsuccessful proposal to permanently enshrine slavery in the United States Constitution, and thereby make it unconstitutional for future congresses to end slavery. It was introduced by United States Senator John J. Crittenden on December 18, 1860. It aimed to resolve the secession crisis of 1860–1861 that eventually led to the American Civil War by addressing the fears and grievances of Southern pro-slavery factions, and by quashing anti-slavery activities. The Crittenden Compromise is not to be confused with the Crittenden Resolution, which provided that the Union would take no actions against slavery.

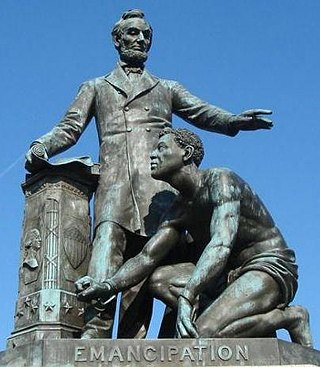

Abraham Lincoln's position on slavery in the United States is one of the most discussed aspects of his life. Lincoln frequently expressed his moral opposition to slavery in public and private. "I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong," he stated. "I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel." However, the question of what to do about it and how to end it, given that it was so firmly embedded in the nation's constitutional framework and in the economy of much of the country, was complex and politically challenging. In addition, there was the unanswered question, which Lincoln had to deal with, of what would become of the four million slaves if liberated: how they would earn a living in a society that had almost always rejected them or looked down on their very presence.

The Peace Conference of 1861 was a meeting of 131 leading American politicians in February 1861, at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., on the eve of the American Civil War. The conference's purpose was to avoid, if possible, the secession of the eight slave states from the upper and border South that had not done so as of that date. The seven states that had already seceded did not attend.

Lyman Trumbull was an American lawyer, judge, and politician who represented the state of Illinois in the United States Senate from 1855 to 1873. Trumbull was a leading abolitionist attorney and key political ally to Abraham Lincoln and authored several landmark pieces of reform as chair of the Judiciary Committee during the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, including the Confiscation Acts, which created the legal basis for the Emancipation Proclamation; the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished chattel slavery; and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which led to the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The presidency of Abraham Lincoln began on March 4, 1861, when Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the 16th president of the United States, and ended upon his assassination and death on April 15, 1865, 42 days into his second term. Lincoln was the first member of the recently established Republican Party elected to the presidency. Lincoln successfully presided over the Union victory in the American Civil War, which dominated his presidency and resulted in the end of slavery.

The presidency of James Buchanan began on March 4, 1857, when James Buchanan was inaugurated as 15th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1861. Buchanan, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, took office as the 15th United States president after defeating former President Millard Fillmore of the American Party, and John C. Frémont of the Republican Party in the 1856 presidential election.

Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address was delivered on Monday, March 4, 1861, as part of his taking of the oath of office for his first term as the sixteenth president of the United States. The speech, delivered at the United States Capitol, was primarily addressed to the people of the South and was intended to succinctly state Lincoln's intended policies and desires toward that section, where seven states had seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America.

Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln is a 2005 book by Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, published by Simon & Schuster. The book is a biographical portrait of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and some of the men who served with him in his cabinet from 1861 to 1865. Three of his Cabinet members had previously run against Lincoln in the 1860 election: Attorney General Edward Bates, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase and Secretary of State William H. Seward. The book focuses on Lincoln's mostly successful attempts to reconcile conflicting personalities and political factions on the path to abolition and victory in the American Civil War.

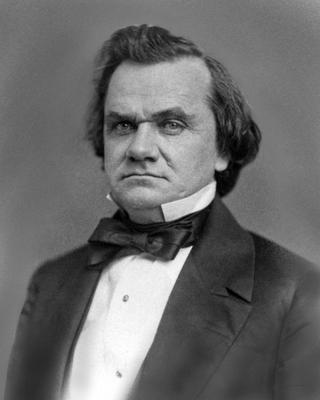

Stephen Arnold Douglas was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was won by Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln. Douglas had previously defeated Lincoln in the 1858 United States Senate election in Illinois, known for the pivotal Lincoln–Douglas debates. He was one of the brokers of the Compromise of 1850 which sought to avert a sectional crisis; to further deal with the volatile issue of extending slavery into the territories, Douglas became the foremost advocate of popular sovereignty, which held that each territory should be allowed to determine whether to permit slavery within its borders. This attempt to address the issue was rejected by both pro-slavery and anti-slavery advocates. Douglas was nicknamed the "Little Giant" because he was short in physical stature but a forceful and dominant figure in politics.

This bibliography of Abraham Lincoln is a comprehensive list of written and published works about or by Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States. In terms of primary sources containing Lincoln's letters and writings, scholars rely on The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy Basler, and others. It only includes writings by Lincoln, and omits incoming correspondence. In the six decades since Basler completed his work, some new documents written by Lincoln have been discovered. Previously, a project was underway at the Papers of Abraham Lincoln to provide "a freely accessible comprehensive electronic edition of documents written by and to Abraham Lincoln". The Papers of Abraham Lincoln completed Series I of their project The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln in 2000. They electronically launched The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln, Second Edition in 2009, and published a selective print edition of this series. Attempts are still being made to transcribe documents for Series II and Series III.

First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln is an 1864 oil-on-canvas painting by Francis Bicknell Carpenter. In the painting, Carpenter depicts Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, and his Cabinet members reading over the Emancipation Proclamation, which proclaimed the freedom of slaves in the ten states in rebellion against the Union in the American Civil War on January 1, 1863. Lincoln presented the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet on July 22, 1862 and issued it on September 22, 1862. The final Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863.

This article documents the political career of Abraham Lincoln from the end of his term in the United States House of Representatives in March 1849 to the beginning of his first term as President of the United States in March 1861.