Related Research Articles

Law enforcement is the activity of some members of government who act in an organized manner to enforce the law by discovering, deterring, rehabilitating, or punishing people who violate the rules and norms governing that society. The term encompasses police, courts, and corrections. These three components may operate independently of each other or collectively, through the use of record sharing and mutual cooperation. Throughout the world, law enforcement are also associated with protecting the public, life, property, and keeping the peace in society.

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health, and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and the use of force legitimized by the state via the monopoly on violence. The term is most commonly associated with the police forces of a sovereign state that are authorized to exercise the police power of that state within a defined legal or territorial area of responsibility. Police forces are often defined as being separate from the military and other organizations involved in the defense of the state against foreign aggressors; however, gendarmerie are military units charged with civil policing. Police forces are usually public sector services, funded through taxes.

Criminal justice is the delivery of justice to those who have been accused of committing crimes. The criminal justice system is a series of government agencies and institutions. Goals include the rehabilitation of offenders, preventing other crimes, and moral support for victims. The primary institutions of the criminal justice system are the police, prosecution and defense lawyers, the courts and the prisons system.

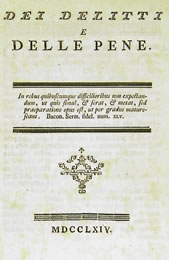

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, Marquis of Gualdrasco and Villareggio was an Italian criminologist, jurist, philosopher, economist and politician, who is widely considered one of the greatest thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment. He is well remembered for his treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764), which condemned torture and the death penalty, and was a founding work in the field of penology and the Classical School of criminology. Beccaria is considered the father of modern criminal law and the father of criminal justice.

Penology is a sub-component of criminology that deals with the philosophy and practice of various societies in their attempts to repress criminal activities, and satisfy public opinion via an appropriate treatment regime for persons convicted of criminal offences.

The Bow Street Runners were the law enforcement officers of the Bow Street Magistrates' Court in the City of Westminster. They have been called London's first professional police force. The force originally numbered six men and was founded in 1749 by magistrate Henry Fielding, who was also well known as an author. Bow Street Runners was the public's nickname for the officers although the officers did not use the term themselves and considered it derogatory. The group was disbanded in 1839 and its personnel merged with the Metropolitan Police. The Metropolitan Police Detective Agency traces their origin back to them.

Right realism, in criminology, also known as New Right Realism, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Positivism, or Neo-Conservatism, is the ideological polar opposite of left realism. It considers the phenomenon of crime from the perspective of political conservatism and asserts that it takes a more realistic view of the causes of crime and deviance, and identifies the best mechanisms for its control. Unlike the other schools of criminology, there is less emphasis on developing theories of causality in relation to crime and deviance. The school employs a rationalist, direct and scientific approach to policy-making for the prevention and control of crime. Some politicians who ascribe to the perspective may address aspects of crime policy in ideological terms by referring to freedom, justice, and responsibility. For example, they may be asserting that individual freedom should only be limited by a duty not to use force against others. This, however, does not reflect the genuine quality in the theoretical and academic work and the real contribution made to the nature of criminal behaviour by criminologists of the school.

In criminology, the classical school usually refers to the 18th-century work during the Enlightenment by the utilitarian and social-contract philosophers Jeremy Bentham and Cesare Beccaria. Their interests lay in the system of criminal justice and penology and indirectly, through the proposition that "man is a calculating animal", in the causes of criminal behavior. The classical school of thought was premised on the idea that people have free will in making decisions, and that punishment can be a deterrent for crime, so long as the punishment is proportional, fits the crime, and is carried out promptly.

In criminology, the Neo-Classical School continues the traditions of the Classical School within the framework of Right Realism. Hence, the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham and Cesare Beccaria remains a relevant social philosophy in policy term for using punishment as a deterrent through law enforcement, the courts, and imprisonment.

The Metropolitan Police Act 1829 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, introduced by Sir Robert Peel, which established the Metropolitan Police. This was to be responsible for policing the newly created Metropolitan Police District, which consisted of the City of Westminster and parts of Middlesex, Surrey, and Kent, within seven miles of Charing Cross, apart from the City of London. It replaced a previously more diverse system of parish constables and watchmen. It is one of the Metropolitan Police Acts 1829 to 1895.

Deterrence in relation to criminal offending is the idea or theory that the threat of punishment will deter people from committing crime and reduce the probability and/or level of offending in society. It is one of five objectives that punishment is thought to achieve; the other four objectives are denunciation, incapacitation, retribution and rehabilitation.

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend." This definition excludes the presence of only a small number of witnesses called upon to assure executive accountability. The purpose of such displays has historically been to deter individuals from defying laws or authorities. Attendance at such events was historically encouraged and sometimes even mandatory.

The sociology of punishment seeks to understand why and how we punish; the general justifying aim of punishment and the principle of distribution. Punishment involves the intentional infliction of pain and/or the deprivation of rights and liberties. Sociologists of punishment usually examine state-sanctioned acts in relation to law-breaking; why, for instance, citizens give consent to the legitimation of acts of violence.

On Crimes and Punishments is a treatise written by Cesare Beccaria in 1764.

The 1832 Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws was a group set up to decide how to change the Poor Law systems in England and Wales. The group included Nassau Senior, a professor from Oxford University who was against the allowance system, and Edwin Chadwick, who was a Benthamite. The recommendations of the Royal Commission's report were implemented in the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834.

Patrick Colquhoun was a Scottish merchant, statistician, magistrate, and founder of the first regular preventive police force in England, the Thames River Police. He also served as Lord Provost of Glasgow 1782 to 1784.

The Thames River Police was formed in 1800 to tackle theft and looting from ships anchored in the Pool of London and in the lower reaches and docks of the Thames. It replaced the Marine Police, a police force established in 1798 by magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and justice of the peace John Harriott that had been part funded by the West India Committee to protect trade between the West Indies and London. It is claimed that the Marine Police was England's first ever police force.

The history of the Metropolitan Police in London is long and complex, with many different events taking place between its inception in 1829 and the present day.

Criminology is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behavioural and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, political scientists, economists, legal sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, social workers, biologists, social anthropologists, scholars of law and jurisprudence, as well as the processes that define administration of justice and the criminal justice system.

The London garrotting panics were two moral panics that occurred in London in 1856 and 1862–63 over a perceived increase in violent street robbery. Garrotting was a term used for robberies in which the victim was strangled to incapacitate them but came to be used as a catch-all term for what is described today as a mugging.

References

- 1 2 3 R. J. Marin, "The Living Law." In eds., W. T. McGrath and M. P. Mitchell, The Police Function in Canada. Toronto: Methuen, 1981, 18-19. ISBN 0-458-93920-X

- ↑ Crymble, Adam (2017-02-09). "How Criminal were the Irish? Bias in the Detection of London Currency Crime, 1797-1821". The London Journal. 43: 36–52. doi: 10.1080/03058034.2016.1270876 . hdl: 2299/19710 .

- ↑ Andrew T. Harris, Policing the City: Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780-1840 Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine PDF. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2004, 6. ISBN 0-8142-0966-1

- ↑ Marjie Bloy, "Edwin Chadwick (1800-1890)," The Victorian Web.

- ↑ E. Chadwick, "A Preventive Police," The London Review, 1829, vol. i, pp. 271-272.

- ↑ Quoted in H. S. Cooper, "The Evolution of Canadian Police." In eds., W. T. McGrath and M. P. Mitchell, The Police Function in Canada. Toronto: Methuen, 1981, 39. ISBN 0-458-93920-X.

- ↑ Charles Reith, "Preventive Principle of Police," Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1931-1951), vol. 34, no. 3 (Sept.-Oct. 1943): 207.

- ↑ T. A. Critchley, A History of Police in England and Wales, 2nd edition. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 38-39.

- ↑ Alastair Dinsmor, "Glasgow Police Pioneers Archived 2009-07-16 at the Wayback Machine ," The Scotia News, vol. 2, no. 1 (Winter 2003).

- ↑ Dick Paterson, Origins of the Thames Police, Thames Police Museum. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- ↑ Mark Neocleous, "Social Police and the Mechanisms of Prevention: Patrick Colquhoun and the Condition of Poverty," British Journal of Criminology, 40 (2000):719-720.