Related Research Articles

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention. In most countries, patent rights fall under private law and the patent holder must sue someone infringing the patent in order to enforce their rights. In some industries patents are an essential form of competitive advantage; in others they are irrelevant.

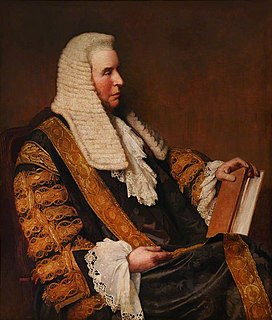

Sir George Jessel, was a British judge. He was one of the most influential commercial law and equity judges of his time, and served as the Master of the Rolls. He was the first Jew to be a regular member of the Privy Council and to hold high judicial office.

Patent infringement is the commission of a prohibited act with respect to a patented invention without permission from the patent holder. Permission may typically be granted in the form of a license. The definition of patent infringement may vary by jurisdiction, but it typically includes using or selling the patented invention. In many countries, a use is required to be commercial to constitute patent infringement.

In United States patent law, utility is a patentability requirement. As provided by 35 U.S.C. § 101, an invention is "useful" if it provides some identifiable benefit and is capable of use and "useless" otherwise. The majority of inventions are usually not challenged as lacking utility, but the doctrine prevents the patenting of fantastic or hypothetical devices such as perpetual motion machines.

An assignment is a legal term used in the context of the law of contract and of property. In both instances, assignment is the process whereby a person, the assignor, transfers rights or benefits to another, the assignee. An assignment may not transfer a duty, burden or detriment without the express agreement of the assignee. The right or benefit being assigned may be a gift or it may be paid for with a contractual consideration such as money.

Freedom of contract is the process in which individuals and groups form contracts without government restrictions. This is opposed to government regulations such as minimum-wage laws, competition laws, economic sanctions, restrictions on price fixing, or restrictions on contracting with undocumented workers. The freedom to contract is the underpinning of laissez-faire economics and is a cornerstone of free-market libertarianism. The proponents of the concept believe that through "freedom of contract", individuals possess a general freedom to choose with whom to contract, whether to contract or not, and on which terms to contract.

Egbert v. Lippmann, 104 U.S. 333 (1881), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that public use of an invention bars the patenting of it. The Court's ruling was colored by its view that the inventor had forfeited his right to patent the invention by "sleeping on his rights" while others commercialized the technology.

This article summarizes the same-sex marriage laws of states in the United States. Via the case Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States legalized same-sex marriage in a decision that applies nationwide, with the exception of American Samoa and sovereign tribal nations.

Consideration is a concept of English common law and is a necessity for simple contracts but not for special contracts. The concept has been adopted by other common law jurisdictions.

The Indian Contract Act, 1872 prescribes the law relating to contracts in India and is the key act regulating Indian contract law. The Act is based on the principles of English Common Law. It is applicable to all the states of India. It determines the circumstances in which promises made by the parties to a contract shall be legally binding. Under Section 2(h), the Indian Contract Act defines a contract as an agreement which is enforceable by law.

A post-sale restraint, also termed a post-sale restriction, as those terms are used in United States patent law and antitrust law, is a limitation that operates after a sale of goods to a purchaser has occurred and purports to restrain, restrict, or limit the scope of the buyer's freedom to utilize, resell, or otherwise dispose of or take action regarding the sold goods. Such restraints have also been termed "equitable servitudes on chattels".

Stanford University v. Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., 563 U.S. 776 (2011), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that title in a patented invention vests first in the inventor, even if the inventor is a researcher at a federally funded lab subject to the 1980 Bayh–Dole Act. The judges affirmed the common understanding of U.S. constitutional law that inventors originally own inventions they make, and contractual obligations to assign those rights to third parties are secondary.

Fawcett Properties Ltd v Buckingham County Council [1960] has become a leading case in planning law and concerned agricultural conditions of use. It is also relevant for its tests on finding certainty versus uncertainty of policy, contract or other concepts rendering them void. It has been applied in English trusts law which has long held a cy-près doctrine, expressed in pre 1649-Law French meaning "there nearly" that is perfecting concepts or a purpose for funds which is tantamount to a legitimate interest or concern and intended to take clear effect.

Holman v Johnson (1775) 1 Cowp 341 is an English contract law case, concerning the principles behind illegal transactions.

Motion Picture Patents Co. v. Universal Film Mfg. Co., 243 U.S. 502 (1917), is United States Supreme Court decision that is notable as an early example of the patent misuse doctrine. It held that, because a patent grant is limited to the invention described in the claims of the patent, the patent law does not empower the patent owner, by notices attached to the patented article, to extend the scope of the patent monopoly by restricting the use of the patented article to materials necessary for their operation but forming no part of the patented invention, or to place downstream restrictions on the articles making them subject to conditions as to use. The decision overruled The Button-Fastener Case, and Henry v. A.B. Dick Co., which had held such restrictive notices effective and enforceable.

Henry v. A.B. Dick Co., 224 U.S. 1 (1912), was a 1912 decision of the United States Supreme Court that upheld patent licensing restrictions such as tie-ins on the basis of the so-called inherency doctrine—the theory that it was the inherent right of a patent owner, because he could lawfully refuse to license his patent at all, to exercise the "lesser" right to license it on any terms and conditions he chose. In 1917, the Supreme Court overruled the A.B. Dick case in Motion Picture Patents Co. v. Universal Film Mfg. Co.,

The Button-Fastener Case, Heaton-Peninsular Button-Fastener Co. v. Eureka Specialty Co., also known as the Peninsular Button-Fastener Case, was for a time a highly influential decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. Many courts of appeals, and the United States Supreme Court in the A.B. Dick case adopted its "inherency doctrine"—"the argument that, since the patentee may withhold his patent altogether from public use, he must logically and necessarily be permitted to impose any conditions which he chooses upon any use which he may allow of it." In 1917, however, the Supreme Court expressly overruled the Button-Fastener Case and the A.B. Dick case, in the Motion Picture Patents case.

Pennock v. Dialogue, 27 U.S. 1 (1829), was a United States Supreme Court decision in which the Court held invalid a patent on a method of making hose, because the inventor had commercially exploited the invention for years before filing the patent application. The case has been cited many times for the proposition that the U.S. patent system was not established for the purpose of enriching inventors or their financiers but rather for the purpose of furthering the public interest by stimulating technological progress.

United States v. Line Material Co., 333 U.S. 287 (1948), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court limiting the doctrine of the 1926 General Electric decision, excusing price fixing in patent license agreements. The Line Material Court held that cross-licenses between two manufacturer competitors, providing for fixing the prices of the licensed products and providing that one of the manufacturers would license other manufacturers under the patents of each manufacturer, subject to similar price fixing, violated Sherman Act § 1. The Court further held that the licensees who, with knowledge of such arrangements, entered into the price-fixing licenses thereby became party to a hub-and-spoke conspiracy in violation of Sherman Act § 1.

Pope Mfg. Co. v. Gormully, 144 U.S. 224 (1892), was an early United States Supreme Court decision refusing, on public policy grounds, to enforce an agreement not to contest patent validity. The Supreme Court later relied on Pope in Lear, Inc. v. Adkins as authority in support of overruling the doctrine of licensee estoppel. That doctrine had prohibited patent licensees from challenging the validity of patents under which they had been licensed.