Related Research Articles

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality. Hallucinations are vivid, substantial, and are perceived to be located in external objective space. Hallucination is a combination of two conscious states of brain wakefulness and REM sleep. They are distinguishable from several related phenomena, such as dreaming, which does not involve wakefulness; pseudohallucination, which does not mimic real perception, and is accurately perceived as unreal; illusion, which involves distorted or misinterpreted real perception; and mental imagery, which does not mimic real perception, and is under voluntary control. Hallucinations also differ from "delusional perceptions", in which a correctly sensed and interpreted stimulus is given some additional significance.

Micropsia is a condition affecting human visual perception in which objects are perceived to be smaller than they actually are. Micropsia can be caused by optical factors, by distortion of images in the eye, by changes in the brain, and from psychological factors. Dissociative phenomena are linked with micropsia, which may be the result of brain-lateralization disturbance.

Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AIWS), also known as Todd's syndrome or dysmetropsia, is a neurological disorder that distorts perception. People with this syndrome may experience distortions in their visual perception of objects, such as appearing smaller (micropsia) or larger (macropsia), or appearing to be closer (pelopsia) or farther (teleopsia) than they are. Distortion may also occur for senses other than vision.

Macropsia is a neurological condition affecting human visual perception, in which objects within an affected section of the visual field appear larger than normal, causing the person to feel smaller than they actually are. Macropsia, along with its opposite condition, micropsia, can be categorized under dysmetropsia. Macropsia is related to other conditions dealing with visual perception, such as aniseikonia and Alice in Wonderland Syndrome. Macropsia has a wide range of causes, from prescription and illicit drugs, to migraines and (rarely) complex partial epilepsy, and to different retinal conditions, such as epiretinal membrane. Physiologically, retinal macropsia results from the compression of cones in the eye. It is the compression of receptor distribution that results in greater stimulation and thus a larger perceived image of an object.

The Fregoli delusion is a rare disorder in which a person holds a delusional belief that different people are in fact a single person who changes appearance or is in disguise. The syndrome may be related to a brain lesion and is often of a paranoid nature, with the delusional person believing themselves persecuted by the person they believe is in disguise.

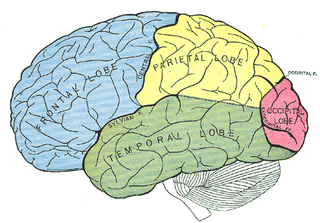

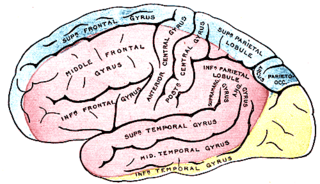

The temporal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The temporal lobe is located beneath the lateral fissure on both cerebral hemispheres of the mammalian brain.

Facial perception is an individual's understanding and interpretation of the face. Here, perception implies the presence of consciousness and hence excludes automated facial recognition systems. Although facial recognition is found in other species, this article focuses on facial perception in humans.

The fusiform gyrus, also known as the lateral occipitotemporal gyrus,is part of the temporal lobe and occipital lobe in Brodmann area 37. The fusiform gyrus is located between the lingual gyrus and parahippocampal gyrus above, and the inferior temporal gyrus below. Though the functionality of the fusiform gyrus is not fully understood, it has been linked with various neural pathways related to recognition. Additionally, it has been linked to various neurological phenomena such as synesthesia, dyslexia, and prosopagnosia.

Bálint's syndrome is an uncommon and incompletely understood triad of severe neuropsychological impairments: inability to perceive the visual field as a whole (simultanagnosia), difficulty in fixating the eyes, and inability to move the hand to a specific object by using vision. It was named in 1909 for the Austro-Hungarian neurologist and psychiatrist Rezső Bálint who first identified it.

An aura is a perceptual disturbance experienced by some with epilepsy or migraine. An epileptic aura is actually a minor seizure.

Focal seizures are seizures that affect initially only one hemisphere of the brain. The brain is divided into two hemispheres, each consisting of four lobes – the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes. A focal seizure is generated in and affects just one part of the brain – a whole hemisphere or part of a lobe. Symptoms will vary according to where the seizure occurs. When seizures occur in the frontal lobe, the patient may experience a wave-like sensation in the head. When seizures occur in the temporal lobe, a feeling of déjà vu may be experienced. When seizures are localized to the parietal lobe, a numbness or tingling may occur. With seizures occurring in the occipital lobe, visual disturbances or hallucinations have been reported.

Visual agnosia is an impairment in recognition of visually presented objects. It is not due to a deficit in vision, language, memory, or intellect. While cortical blindness results from lesions to primary visual cortex, visual agnosia is often due to damage to more anterior cortex such as the posterior occipital and/or temporal lobe(s) in the brain.[2] There are two types of visual agnosia: apperceptive agnosia and associative agnosia.

The posterior cerebral artery (PCA) is one of a pair of cerebral arteries that supply oxygenated blood to the occipital lobe, part of the back of the human brain. The two arteries originate from the distal end of the basilar artery, where it bifurcates into the left and right posterior cerebral arteries. These anastomose with the middle cerebral arteries and internal carotid arteries via the posterior communicating arteries.

Akinetopsia, also known as cerebral akinetopsia or motion blindness, is a term introduced by Semir Zeki to describe an extremely rare neuropsychological disorder, having only been documented in a handful of medical cases, in which a patient cannot perceive motion in their visual field, despite being able to see stationary objects without issue. The syndrome is the result of damage to visual area V5, whose cells are specialized to detect directional visual motion. There are varying degrees of akinetopsia: from seeing motion as frames of a cinema reel to an inability to discriminate any motion. There is currently no effective treatment or cure for akinetopsia.

Phantosmia, also called an olfactory hallucination or a phantom odor, is smelling an odor that is not actually there. This is intrinsically suspicious as the formal evaluation and detection of relatively low levels of odour particles is itself a very tricky task in air epistemology. It can occur in one nostril or both. Unpleasant phantosmia, cacosmia, is more common and is often described as smelling something that is burned, foul, spoiled, or rotten. Experiencing occasional phantom smells is normal and usually goes away on its own in time. When hallucinations of this type do not seem to go away or when they keep coming back, it can be very upsetting and can disrupt an individual's quality of life.

The fusiform face area is a part of the human visual system that is specialized for facial recognition. It is located in the inferior temporal cortex (IT), in the fusiform gyrus.

Prosopamnesia is a selective neurological impairment in the ability to learn new faces. There is a special neural circuit for the processing of faces as opposed to other non-face objects. Prosopamnesia is a deficit in the part of this circuit responsible for encoding perceptions as memories.

Idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut (ICOE-G) is a pure but rare form of idiopathic occipital epilepsy that affects otherwise normal children and adolescents. It is classified amongst benign idiopathic childhood focal epilepsies such as rolandic epilepsy and Panayiotopoulos syndrome.

Occipital epilepsy is a neurological disorder that arises from excessive neural activity in the occipital lobe of the brain that may or may not be symptomatic. Occipital lobe epilepsy is fairly rare, and may sometimes be misdiagnosed as migraine when symptomatic. Epileptic seizures are the result of synchronized neural activity that is excessive, and may stem from a failure of inhibitory neurons to regulate properly.

The occipital face area (OFA) is a region of the human cerebral cortex which is specialised for face perception. The OFA is located on the lateral surface of the occipital lobe adjacent to the inferior occipital gyrus. The OFA comprises a network of brain regions including the fusiform face area (FFA) and posterior superior temporal sulcus (STS) which support facial processing.

References

- ↑ Talia Naquin (March 22, 2024). "Demon face syndrome pictures". Fox 8 . Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ↑ Sarah Al-Arshani (March 28, 2024). "What causes prosopometamorphopsia, the rare 'demon-face syndrome' PMO". USA Today . Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ↑ Duchaine, Brad. "Understanding Prosopometamorphopsia (PMO)".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dalrymple, Kirsten; Davies-Thompson, Jodie; Oruc, Ipek; Barton, Jason; Duchaine, Brad (2014). "Spontaneous Perceptual Facial Distortions Correlate with Ventral Occipitotemporal Activity". Neuropsychologia . 59: 179–191. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.05.005. PMID 24859691. S2CID 6996193.

- 1 2 3 Santhouse, A M; Howard, R J; ffytche, D H (2000). "Visual Hallucinatory Syndromes and the Anatomy of the Visual Brain". Brain . 123 (10): 2055–2064. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.10.2055 . PMID 11004123.

- 1 2 3 4 ffytche, D H; Howard, R J (1999). "The Perceptual Consequences of Visual Loss: 'Positive' Pathologies of Vision". Brain . 122 (7): 1257–1260. doi:10.1093/brain/122.7.1247. PMID 10388791.

- 1 2 3 Hwang, Jung Yun; Ha, Sang Won; Cho, Eun Kyoung; Han, Jeong Ho; Lee, Seon Hwa; Lee, Seung Yeon; Kim, Doo Eung (2012). "A Case of Prosopometamorphopsia Restricted to the Nose and Mouth with Right Medial Temporooccipital Lobe Infarction That Included the Fusiform Face Area". Journal of Clinical Neurology. 8 (4): 311–313. doi:10.3988/jcn.2012.8.4.311. PMC 3540293 . PMID 23323142.

- 1 2 Mocellin, Ramon; Walterfang, Mark; Velakoulis, Dennis (2006). "Neuropsychiatry of Complex Visual Hallucinations". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry . 40 (9): 742–751. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01878.x. PMID 16911748. S2CID 12151224.

- 1 2 3 Trojano, Luigi; Conson, Massimiliano; Salzano, Sara; Manzo, Valentino; Grossi, Dario (2009). "Unilateral Left Prosopometamorphopsia: A Neuropsychological Case Study". Neuropsychologia . 47 (3): 942–948. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.12.015. PMID 19136018. S2CID 1900190.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blom, Jan Dirk; Sommer, Iris; Koops, Sanne; Sacks, Oliver (2014). "Prosopometamorphopsia and Facial Hallucinations". The Lancet . 384 (9958): 1998. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61690-1. PMID 25435453. S2CID 19780355.