Sexual assault is an act in which one intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will. It is a form of sexual violence that includes child sexual abuse, groping, rape, drug facilitated sexual assault, and the torture of the person in a sexual manner.

Some victims of rape or other sexual violence incidents are male. It is estimated that approximately one in six men experienced sexual abuse during childhood. Historically, rape was thought to be, and defined as, a crime committed solely against females. This belief is still held in some parts of the world, but rape of males is now commonly criminalized and has been subject to more discussion than in the past.

Sexual grooming is the action or behavior used to establish an emotional connection with a minor, and sometimes the child's family, to lower the child's inhibitions with the objective of sexual abuse. It can occur in various settings, including online, in person, and through other means of communication. Children who are groomed may experience mental health issues, including "anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and suicidal thoughts."

The precise definitions of and punishments for aggravated sexual assault and aggravated rape vary by country and by legislature within a country.

The legal age of consent for sexual activity varies by jurisdiction across Asia. The specific activity engaged in or the gender of participants can also be relevant factors. Below is a discussion of the various laws dealing with this subject. The highlighted age refers to an age at or above which an individual can engage in unfettered sexual relations with another who is also at or above that age. Other variables, such as homosexual relations or close in age exceptions, may exist, and are noted when relevant.

The ages of consent vary by jurisdiction across Europe. The ages of consent – hereby meaning the age from which one is deemed able to consent to having sex with anyone else of consenting age or above – are between 14 and 18. The vast majority of countries set their ages in the range of 14 to 16; only four countries, Cyprus (17), Ireland (17), Turkey (18), and the Vatican City (18), set an age of consent higher than 16.

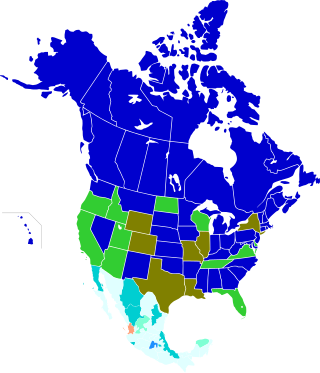

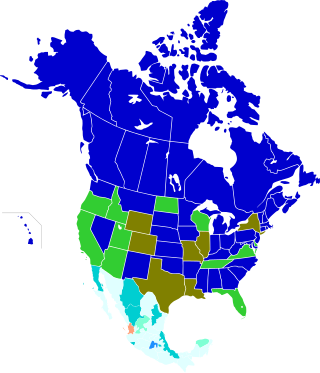

In North America, the legal age of consent relating to sexual activity varies by jurisdiction.

The age of consent in Africa for sexual activity varies by jurisdiction across the continent, codified in laws which may also stipulate the specific activities that are permitted or the gender of participants for different ages. Other variables may exist, such as close-in-age exemptions.

Rape is a type of sexual assault initiated by one or more persons against another person without that person's consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, under threat or manipulation, by impersonation, or with a person who is incapable of giving valid consent.

Laws against child sexual abuse vary by country based on the local definition of who a child is and what constitutes child sexual abuse. Most countries in the world employ some form of age of consent, with sexual contact with an underage person being criminally penalized. As the age of consent to sexual behaviour varies from country to country, so too do definitions of child sexual abuse. An adult's sexual intercourse with a minor below the legal age of consent may sometimes be referred to as statutory rape, based on the principle that any apparent consent by a minor could not be considered legal consent.

In common law jurisdictions, statutory rape is nonforcible sexual activity in which one of the individuals is below the age of consent. Although it usually refers to adults engaging in sexual contact with minors under the age of consent, it is a generic term, and very few jurisdictions use the actual term statutory rape in the language of statutes. In statutory rape, overt force or threat is usually not present. Statutory rape laws presume coercion because a minor or mentally disabled adult is legally incapable of giving consent to the act.

There are a number of sexual offences under the law of England and Wales, the law of Scotland, and the law of Northern Ireland.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 2007 is an act of the Parliament of South Africa that reformed and codified the law relating to sex offences. It repealed various common law crimes and replaced them with statutory crimes defined on a gender-neutral basis. It expanded the definition of rape, previously limited to vaginal sex, to include all non-consensual penetration; and it equalised the age of consent for heterosexual and homosexual sex at 16. The act provides various services to the victims of sexual offences, including free post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV, and the ability to obtain a court order to compel HIV testing of the alleged offender. It also created the National Register for Sex Offenders, which records the details of those convicted of sexual offences against children or people who are mentally disabled.

Domestic violence in India includes any form of violence suffered by a person from a biological relative but typically is the violence suffered by a woman by male members of her family or relatives. Although Men also suffer Domestic violence, the law under IPC 498A specifically protects only women. Specifically only a woman can file a case of domestic violence. According to a National Family and Health Survey in 2005, total lifetime prevalence of domestic violence was 33.5% and 8.5% for sexual violence among women aged 15–49. A 2014 study in The Lancet reports that although the reported sexual violence rate in India is among the lowest in the world, the large population of India means that the violence affects 27.5 million women over their lifetimes. However, an opinion survey among experts carried out by the Thomson Reuters Foundation ranked India as the most dangerous country in the world for women.

Rape is the fourth most common crime against women in India. According to the 2021 annual report of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), 31,677 rape cases were registered across the country, or an average of 86 cases daily, a rise from 2020 with 28,046 cases, while in 2019, 32,033 cases were registered. Of the total 31,677 rape cases, 28,147 of the rapes were committed by persons known to the victim. The share of victims who were minors or below 18 – the legal age of consent – stood at 10%.

The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 is an Indian legislation passed by the Lok Sabha on 19 March 2013, and by the Rajya Sabha on 21 March 2013, which provides for amendment of Indian Penal Code, Indian Evidence Act, and Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 on laws related to sexual offences. The Bill received Presidential assent on 2 April 2013 and was deemed to be effective from 3 February 2013. It was originally an Ordinance promulgated by the President of India, Pranab Mukherjee, on 3 February 2013, in light of the protests in the 2012 Delhi gang rape case.

Child sexual abuse in Nigeria is an offence under several sections of chapter 21 of the country's criminal code. The age of consent is 18.

Aarambh India is a non-profit initiative working in Mumbai, India. It focuses on child protection and issues related to child sexual abuse and exploitation. The organization was established in 2012. It partners with other organizations and stakeholders and works across levels from implementing the Protection of Children against Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2011 on the ground for organizing trainings and workshops, providing care and support to the victims and engage in research on child sexual abuse, public education and advocacy.

Bharati Harish Dangre is a sitting judge of the Bombay High Court in Maharashtra, India. Dangre has adjudicated in several significant cases concerning constitutional law, including the validity of affirmative action in the form of reservations for the Maratha caste in Maharashtra, the interpretation of child sexual abuse laws in India, and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax in India.

Pushpa Virendra Ganediwala is an Indian lawyer. She was previously an additional judge of the Bombay High Court, but resigned in 2022, after the Supreme Court of India took the unusual step of refusing to confirm her appointment to the High Court as permanent, after she delivered several controversial judgments concerning cases of sexual assaults against women and children.