Cloture, closure or, informally, a guillotine, is a motion or process in parliamentary procedure aimed at bringing debate to a quick end.

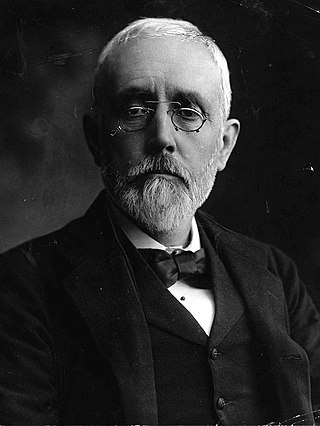

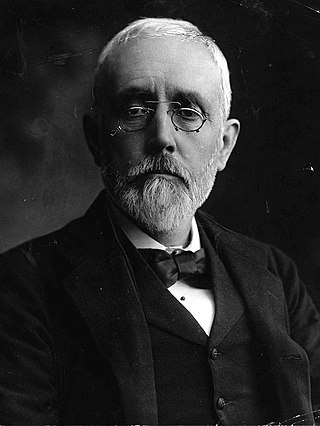

William Edward Forster, PC, FRS was an English industrialist, philanthropist and Liberal Party statesman. His purported advocacy of the Irish Constabulary's use of lethal force against the National Land League earned him the nickname Buckshot Forster from Irish nationalists.

The Irish Parliamentary Party was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament (MPs) elected to the House of Commons at Westminster within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland up until 1918. Its central objectives were legislative independence for Ireland and land reform. Its constitutional movement was instrumental in laying the groundwork for Irish self-government through three Irish Home Rule bills.

William O'Brien was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. He was particularly associated with the campaigns for land reform in Ireland during the late 19th and early 20th centuries as well as his conciliatory approach to attaining Irish Home Rule.

John Dillon was an Irish politician from Dublin, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years and was the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. By political disposition Dillon was an advocate of Irish nationalism, originally a follower of Charles Stewart Parnell, supporting land reform and Irish Home Rule.

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. Unlike the first attempt, which was defeated in the House of Commons, the second Bill was passed by the Commons but vetoed by the House of Lords.

The Land Acts were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by the government of the United Kingdom between 1870 and 1909. Further acts were introduced by the governments of the Irish Free State after 1922 and more acts were passed for Northern Ireland.

Michael Davitt was an Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's family migrated to England. He began his career as an organiser of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which resisted British rule in Ireland with violence. Convicted of treason felony for arms trafficking in 1870, he served seven years in prison. Upon his release, Davitt pioneered the New Departure strategy of cooperation between the physical-force and constitutional wings of Irish nationalism on the issue of land reform. With Charles Stewart Parnell, he co-founded the Irish National Land League in 1879, in which capacity he enjoyed the peak of his influence before being jailed again in 1881.

Arson in royal dockyards and armories was a criminal offence in the United Kingdom and the British Empire. It was among the last offences that were punishable by capital punishment in the United Kingdom. The crime was created by the Dockyards etc. Protection Act 1772 passed by the Parliament of Great Britain, which was designed to prevent arson and sabotage against vessels, dockyards, and arsenals of the Royal Navy.

The Kilmainham Treaty was an informal agreement reached in May 1882 between Liberal British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone and the Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell. Whilst in gaol, Parnell moved in April 1882 to make a deal with the government, negotiated through Captain William O'Shea MP. The government would settle the "rent arrears" question allowing 100,000 tenants to appeal for fair rent before the land courts. Parnell promised to use his good offices to quell the violence and to co-operate cordially for the future with the Liberal Party in forwarding Liberal principles and measures of general reform. Gladstone released the prisoner and the agreement was a major triumph for Irish nationalism as it won abatement for tenant rent-arrears from the Government at the height of the Land War.

The Land War was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 1882, or include later outbreaks of agitation that periodically reignited until 1923, especially the 1886–1891 Plan of Campaign and the 1906–1909 Ranch War. The agitation was led by the Irish National Land League and its successors, the Irish National League and the United Irish League, and aimed to secure fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure for tenant farmers and ultimately peasant proprietorship of the land they worked.

A Coercion Act was an Act of Parliament that gave a legal basis for increased state powers to suppress popular discontent and disorder. The label was applied, especially in Ireland, to acts passed from the 18th to the early 20th century by the Irish, British, and Northern Irish parliaments.

John Joseph Clancy, usually known as J. J. Clancy, was an Irish nationalist politician and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons for North Dublin from 1885 to 1918. He was one of the leaders of the later Irish Home Rule movement and promoter of the Housing of the Working Classes (Ireland) Act 1908, known as the Clancy Act. Called to the Irish Bar in 1887, he became a King's Counsel in 1906.

James Gilhooly (1847–1916) was an Irish nationalist politician and MP. in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as member of the Irish Parliamentary Party, from 1910 the All-for Ireland Party, who represented his constituency from 1885 for 30 years until his death, retaining his seat in eight elections.

The Plan of Campaign was a stratagem adopted in Ireland between 1886 and 1891, co-ordinated by Irish politicians for the benefit of tenant farmers, against mainly absentee and rack-rent landlords. It was launched to counter agricultural distress caused by the continual depression in prices of dairy products and cattle from the mid-1870s, which left many tenants in arrears with rent. Bad weather in 1885 and 1886 also caused crop failure, making it harder to pay rents. The Land War of the early 1880s was about to be renewed after evictions increased and outrages became widespread.

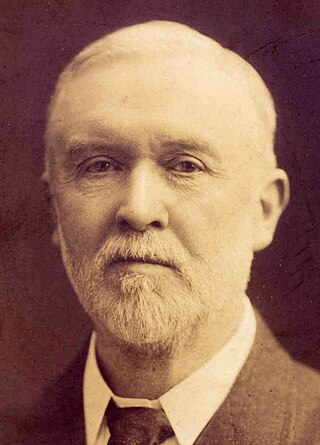

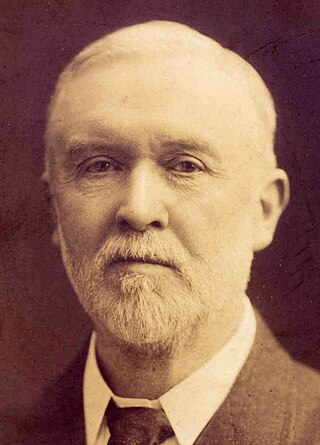

Thomas Sexton (1848–1932) was an Irish journalist, financial expert, nationalist politician and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1880 to 1896, representing four different constituencies. He was High Sheriff of County Dublin in 1887 and Lord Mayor of Dublin from 1888 to 1890. Sexton was a high ranking member of the Irish Parliamentary Party, raised up by Charles Stewart Parnell himself. However, Sexton broke with Parnell and joined the Anti-Parnellites in 1891 following Parnell's marriage scandal. Sexton was disheartened by the subsequent infighting amongst the Anti-Parnellites and pulled back from politics. He thereafter became the chairman of the Freeman's Journal, one of the largest newspapers in Ireland.

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of World War I.

The Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881 was the second Irish land act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

The Criminal Law and Procedure (Ireland) Act 1887 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which amended the criminal law in Ireland to give greater law enforcement power to the authorities. It was introduced by Arthur Balfour, then Chief Secretary for Ireland, to deal with the Plan of Campaign, an increase in illegal activity associated with the Land War. It was informally called the Crimes Act, Irish Crimes Act, or Perpetual Crimes Act; or the Jubilee Coercion Act.

The Irish Council Bill was a bill introduced and withdrawn from the UK Parliament in 1907 by the Campbell-Bannerman administration. It proposed the devolution of power, without Home Rule, to Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. A partly elected Irish Council would take control of many of the departments thitherto administered by the Dublin Castle administration, and have limited tax-raising powers. The bill was introduced by Augustine Birrell, the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, on 7 May 1907. It was rejected by the United Irish League (UIL) at a conference in Dublin on 21 May, which meant the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) aligned to the UIL would oppose it in Parliament. Henry Campbell-Bannerman announced on 3 June that the government was dropping the bill, and it was formally withdrawn on 29 July.