Related Research Articles

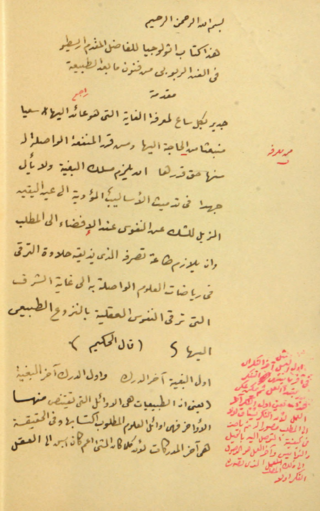

The Emerald Tablet, also known as the Smaragdine Tablet or the Tabula Smaragdina, is a compact and cryptic Hermetic text. It was highly regarded by Islamic and European alchemists as the foundation of their art. Though attributed to the legendary Hellenistic figure Hermes Trismegistus, the text of the Emerald Tablet first appears in a number of early medieval Arabic sources, the oldest of which dates to the late eighth or early ninth century. It was translated into Latin several times in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Numerous interpretations and commentaries followed.

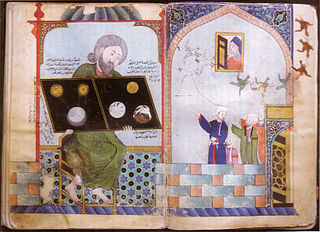

The Secretum Secretorum or Secreta Secretorum, also known as the Sirr al-Asrar, is a treatise which purports to be a letter from Aristotle to his student Alexander the Great on an encyclopedic range of topics, including statecraft, ethics, physiognomy, astrology, alchemy, magic, and medicine. The earliest extant editions claim to be based on a 9th-century Arabic translation of a Syriac translation of the lost Greek original. It is a pseudo-Aristotelian work. Modern scholarship finds it likely to have been written in the 10th century in Arabic. Translated into Latin in the mid-12th century, it was influential among European intellectuals during the High Middle Ages.

The Secretum philosophorum was a popular Latin text originating in England c.1300–1350. Ostensibly a treatise on the Seven Liberal Arts, it merely uses them as a framework in which to describe and demystify practical tricks, ‘tricks of the trade’ and applied science.

The Kitāb al-Ḥayawān is an Arabic translation of treatises of Aristotle's:

The Categoriae decem, also known as the Paraphrasis Themistiana, is a Latin summary of the Categories of Aristotle. It is thought to date to the fourth century AD. Once and traditionally attributed to Augustine of Hippo, it is no longer thought to be his work.

The Theology of Aristotle, also called Theologia Aristotelis is a paraphrase in Arabic of parts of Plotinus' Six Enneads along with Porphyry's commentary. It was traditionally attributed to Aristotle, but as this attribution is certainly untrue it is conventional to describe the author as "Pseudo-Aristotle". It had a significant effect on early Islamic philosophy, due to Islamic interest in Aristotle. Al-Kindi (Alkindus) and Avicenna, for example, were influenced by Plotinus' works as mediated through the Theology and similar works. The translator attempted to integrate Aristotle's ideas with those of Plotinus — while trying to make Plotinus compatible with Christianity and Islam, thus yielding a unique synthesis.

The Thomas-Institut is a research Institute whose function is to study of medieval philosophy by preparing critical editions as well as historical and systematic studies of medieval authors.

Ptolemy-el-Garib was a Hellenistic pinacographer, probably of the Peripatetic school, who wrote a Life of Aristotle notable for its catalog of Aristotle's works. This work survives in an Arabic manuscript in Istanbul. A critical edition, with French translation was published by Marwan Rashed.

Jofroi of Waterford was a French translator.

During the High Middle Ages, the Islamic world was at its cultural peak, supplying information and ideas to Europe, via Al-Andalus, Sicily and the Crusader kingdoms in the Levant. These included Latin translations of the Greek Classics and of Arabic texts in astronomy, mathematics, science, and medicine. Translation of Arabic philosophical texts into Latin "led to the transformation of almost all philosophical disciplines in the medieval Latin world", with a particularly strong influence of Muslim philosophers being felt in natural philosophy, psychology and metaphysics. Other contributions included technological and scientific innovations via the Silk Road, including Chinese inventions such as paper, compass and gunpowder.

Physiognomonics is an Ancient Greek pseudo-Aristotelian treatise on physiognomy attributed to Aristotle.

Amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas is a Latin phrase, translating to "Plato is my friend, but truth is a better friend ." The maxim is often attributed to Aristotle, as a paraphrase of the Nicomachean Ethics 1096a11–15.

The Liber de causis is a philosophical work composed in Arabic in the 9th century. It was once attributed to Aristotle and became popular in West during the Middle Ages, after it was translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona between 1167 and 1187. The original title was كتاب الإيضاح لأرسطوطاليس في الخير المحض Kitāb al-Īḍāḥ li-Arisṭūṭālis fī l-khayr al-maḥd, "The book of Aristotle's explanation of the pure good". Its Latin title, Liber de causis, came into use following its translation. The work was also translated into Armenian and Hebrew. Many Latin commentaries on the work are extant.

Alchemy in the medieval Islamic world refers to both traditional alchemy and early practical chemistry by Muslim scholars in the medieval Islamic world. The word alchemy was derived from the Arabic word كيمياء or kīmiyāʾ and may ultimately derive from the ancient Egyptian word kemi, meaning black.

Robert Steele (1860–1944) was a British scholar, best known for editing between c. 1905 and 1941 the 16-volume Opera hactenus inedita Rogeri Bacon.

Pseudo-Augustine is the name given by scholars to the authors, collectively, of works falsely attributed to Augustine of Hippo. Augustine himself in his Retractiones lists many of his works, while his disciple Possidius tried to provide a complete list in his Indiculus. Despite this check, false attributions to Augustine abound.

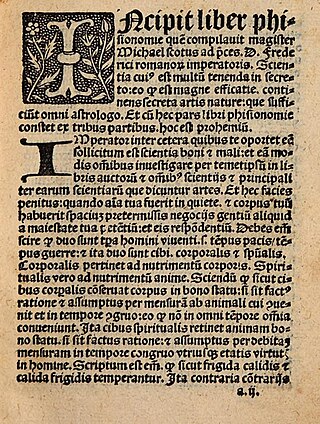

Liber physiognomiae is a work by the Scottish mathematician, philosopher, and scholar Michael Scot concerning physiognomy; the work is also the final book of a trilogy known as the Liber introductorius. The Liber physiognomiae itself is divided into three sections, which deal with various concepts like procreation, generation, dream interpretation, and physiognomy proper.

The Elements of Theology is a work on Neoplatonic philosophy written by Proclus. Conceived of as a systematic summary of Neoplatonic metaphysics, it has often served as a general introduction to this subject.

Philip of Tripoli, sometimes Philippus Tripolitanus or Philip of Foligno, was an Italian Catholic priest and translator. Although he had a markedly successful clerical career, his most enduring legacy is his translation of the complete Pseudo-Aristotelian Secretum secretorum from Arabic into Latin around 1230.

Guyof Valence was a bishop of Tripoli whose episcopate probably fell in the period 1228–1237. He is an obscure figure, whose name is known only from the prologue of Philip of Tripoli's Latin translation of the Pseudo-Aristotelian Secretum secretorum, in which he dedicates the work "to his most excellent lord Guido, originally of Valence, glorious pontiff of the city of Tripoli, most strenuous in the cultivation of the Christian religion."

References

- 1 2 Glick, Livesey & Wallis 2005, p. 423–424.

- ↑ Kieckhefer 2000, p. 27.

- ↑ Charles B. Schmitt, Dilwyn Knox (Eds.): Pseudo-Aristoteles Latinus. A Guide to Latin works falsely attributed to Aristotle before 1500. London: The Warburg Institute, 1985, ISBN 0-85481-066-8 (Warburg Institute Surveys and Texts 12).

- ↑ Bullough 1973.