The ferns are a group of vascular plants that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissues that conduct water and nutrients and in having life cycles in which the branched sporophyte is the dominant phase.

The lycophytes, when broadly circumscribed, are a group of vascular plants that include the clubmosses. They are sometimes placed in a division Lycopodiophyta or Lycophyta or in a subdivision Lycopodiophytina. They are one of the oldest lineages of extant (living) vascular plants; the group contains extinct plants that have been dated from the Silurian. Lycophytes were some of the dominating plant species of the Carboniferous period, and included the tree-like Lepidodendrales, some of which grew over 40 metres (130 ft) in height, although extant lycophytes are relatively small plants.

In plant anatomy and evolution a microphyll is a type of plant leaf with one single, unbranched leaf vein. Plants with microphyll leaves occur early in the fossil record, and few such plants exist today. In the classical concept of a microphyll, the leaf vein emerges from the protostele without leaving a leaf gap. Leaf gaps are small areas above the node of some leaves where there is no vascular tissue, as it has all been diverted to the leaf. Megaphylls, in contrast, have multiple veins within the leaf and leaf gaps above them in the stem.

A pteridophyte is a vascular plant that reproduces by means of spores. Because pteridophytes produce neither flowers nor seeds, they are sometimes referred to as "cryptogams", meaning that their means of reproduction is hidden.

Psilotaceae is a family of ferns consisting of two genera, Psilotum and Tmesipteris with about a dozen species. It is the only family in the order Psilotales.

Cooksonia is an extinct group of primitive land plants, treated as a genus, although probably not monophyletic. The earliest Cooksonia date from the middle of the Silurian ; the group continued to be an important component of the flora until the end of the Early Devonian, a total time span of 433 to 393 million years ago. While Cooksonia fossils are distributed globally, most type specimens come from Britain, where they were first discovered in 1937. Cooksonia includes the oldest known plant to have a stem with vascular tissue and is thus a transitional form between the primitive non-vascular bryophytes and the vascular plants.

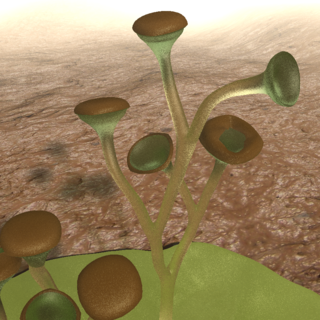

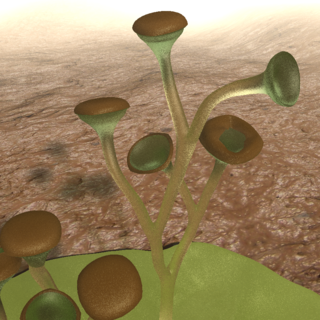

The rhyniophytes are a group of extinct early vascular plants that are considered to be similar to the genus Rhynia, found in the Early Devonian. Sources vary in the name and rank used for this group, some treating it as the class Rhyniopsida, others as the subdivision Rhyniophytina or the division Rhyniophyta. The first definition of the group, under the name Rhyniophytina, was by Banks, since when there have been many redefinitions, including by Banks himself. "As a result, the Rhyniophytina have slowly dissolved into a heterogeneous collection of plants ... the group contains only one species on which all authors agree: the type species Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii". When defined very broadly, the group consists of plants with dichotomously branched, naked aerial axes ("stems") with terminal spore-bearing structures (sporangia). The rhyniophytes are considered to be stem group tracheophytes.

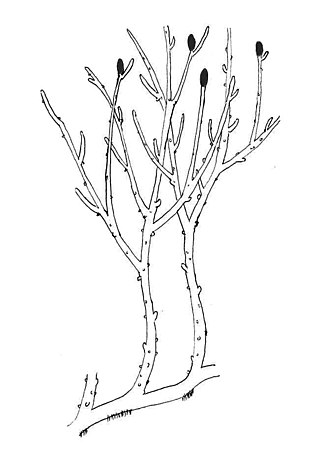

Psilotum nudum, the whisk fern, is a fernlike plant. Like the other species in the order Psilotales, it lacks roots.

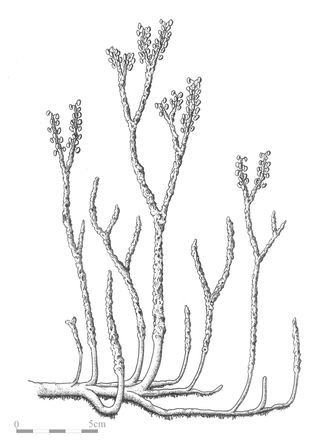

Psilotum complanatum, the flatfork fern, is a rare herbaceous epiphytic fern ally in the genus Psilotum. There is some evidence that it might be a true fern that has lost some typically fern-like characteristics. Morphologically, the plant is simple, lacking leaves and roots, and having hanging stems with dichotomous branching, which lack developed leaves but have minute scales. The stems and branches have protostele, with a triangular-shaped core of xylem. The scales are arranged in two rows along the flat stems and branches. The stems are broadly triangular in cross section and 5 mm wide. The branches are 1.5 to 2 mm wide. P. complanatum grows 10 to 75 cm long and stems branch in pairs a number of times up their length and are covered with brownish colored hair-like rhizoids. Small stalks end with simple sporangia from the axils of minute bifid, rounded sporophylls. Bean shaped, monolete spores are produced. The spores germinate best in a dark environment when ammonium is present. The gametophyte is non-photosynthetic, living in association with a fungus for its nutritional needs. Plants grow from a subterranean rhizome which anchors the plant in place and absorbs nutrients by means of filament like rhizoids.

Polysporangiophytes, also called polysporangiates or formally Polysporangiophyta, are plants in which the spore-bearing generation (sporophyte) has branching stems (axes) that bear sporangia. The name literally means 'many sporangia plant'. The clade includes all land plants (embryophytes) except for the bryophytes whose sporophytes are normally unbranched, even if a few exceptional cases occur. While the definition is independent of the presence of vascular tissue, all living polysporangiophytes also have vascular tissue, i.e., are vascular plants or tracheophytes. Extinct polysporangiophytes are known that have no vascular tissue and so are not tracheophytes.

Aglaophyton major was the sporophyte generation of a diplohaplontic, pre-vascular, axial, free-sporing land plant of the Lower Devonian. It had anatomical features intermediate between those of the bryophytes and vascular plants or tracheophytes.

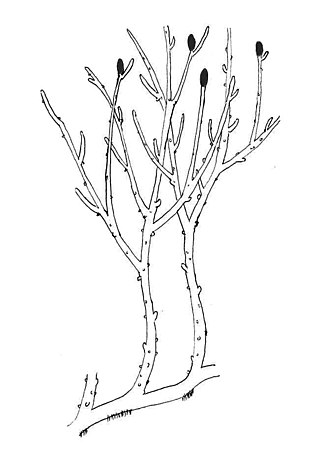

Horneophyton is an extinct early plant which may form a "missing link" between the hornworts and the Rhyniopsida. It is a member of the class Horneophytopsida. Horneophyton is among the most abundant fossil organisms found in the Rhynie chert, a Devonian Lagerstätte in Aberdeenshire, UK. A single species, Horneophyton lignieri, is known. Its probable female gametophyte is the form taxon Langiophyton mackiei.

Psilophytopsida is a now obsolete class containing one order, Psilophytales, which was previously used to classify a number of extinct plants which are now placed elsewhere. The class was established in 1917, under the name Psilophyta, with only three genera for a group of fossil plants from the Upper Silurian and Devonian periods which lack true roots and leaves, but have a vascular system within a branching cylindrical stem. The living Psilotaceae, the whisk-ferns, were sometimes added to the class, which was then usually called Psilopsida. This classification is no longer in use.

Hicklingia is a genus of extinct plants of the Middle Devonian. Compressed specimens were first described in 1923 from the Old Red Sandstone of Scotland. Initially the genus was placed in the "rhyniophytes", but this group is defined as having terminal sporangia, and later work showed that the sporangia of Hicklingia were lateral rather than strictly terminal, so that it is now regarded as having affinities with the zosterophylls.

Huia is a genus of extinct vascular plants of the Early Devonian. The genus was first described in 1985 based on fossil specimens from the Posongchong Formation, Wenshan district, Yunnan, China.

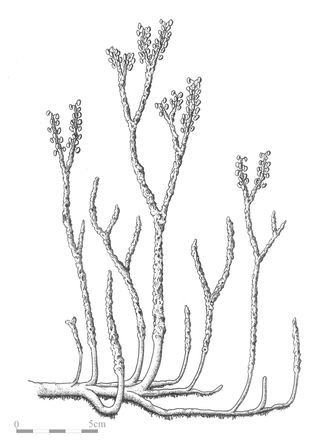

Nothia was a genus of Early Devonian vascular plants whose fossils were found in the Rhynie chert in Scotland. It had branching horizontal underground stems (rhizomes) and leafless aerial stems (axes) bearing lateral and terminal spore-forming organs (sporangia). Its aerial stems were covered with small 'bumps' (emergences), each bearing a stoma. It is one of the best described early land plants. Its classification remains uncertain, although it has been treated as a zosterophyll. There is one species, Nothia aphylla.

Junggaria was a genus of rhyniophyte-like land plants known from fossils found in China in Upper Silurian strata. It bore leafless dichotomously or pseudomonopodially branching axes, some of which ended in spore-forming organs or sporangia of complex shape. The genus Cooksonella, found in Kazakhstan from deposits of a similar age, is considered to be an illegitimate synonym.

Asterotheca is a genus of seedless, spore-bearing, vascularized ferns dating from the Carboniferous of the Paleozoic to the Triassic of the Mesozoic.

Tmesipteris obliqua, more commonly known as the long fork-fern or common fork-fern, is a weeping, epiphytic fern ally with narrow unbranched leafy stems. T. obliqua is a member of the genus Tmesipteris, commonly known as hanging fork-ferns. Tmesipteris is one of two genera in the order Psilotales, the other genus being Psilotum. T. obliqua is endemic to eastern Australia.

Tmesipteris horomaka, commonly known as the Banks Peninsula fork fern, is a fern ally endemic to New Zealand.