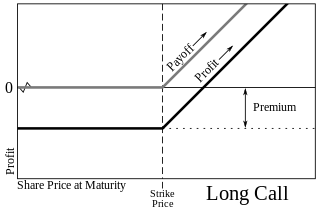

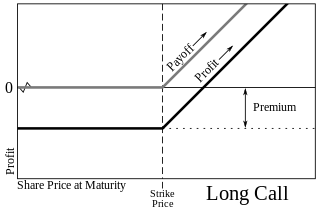

In finance, a call option, often simply labeled a "call", is a contract between the buyer and the seller of the call option to exchange a security at a set price. The buyer of the call option has the right, but not the obligation, to buy an agreed quantity of a particular commodity or financial instrument from the seller of the option at or before a certain time for a certain price. This effectively gives the owner a long position in the given asset. The seller is obliged to sell the commodity or financial instrument to the buyer if the buyer so decides. This effectively gives the seller a short position in the given asset. The buyer pays a fee for this right. The term "call" comes from the fact that the owner has the right to "call the stock away" from the seller.

In finance, a warrant is a security that entitles the holder to buy or sell stock, typically the stock of the issuing company, at a fixed price called the exercise price.

In finance, a straddle strategy involves two transactions in options on the same underlying, with opposite positions. One holds long risk, the other short. As a result, it involves the purchase or sale of particular option derivatives that allow the holder to profit based on how much the price of the underlying security moves, regardless of the direction of price movement.

In finance, the style or family of an option is the class into which the option falls, usually defined by the dates on which the option may be exercised. The vast majority of options are either European or American (style) options. These options—as well as others where the payoff is calculated similarly—are referred to as "vanilla options". Options where the payoff is calculated differently are categorized as "exotic options". Exotic options can pose challenging problems in valuation and hedging.

In finance, a futures contract is a standardized legal contract to buy or sell something at a predetermined price for delivery at a specified time in the future, between parties not yet known to each other. The asset transacted is usually a commodity or financial instrument. The predetermined price of the contract is known as the forward price. The specified time in the future when delivery and payment occur is known as the delivery date. Because it derives its value from the value of the underlying asset, a futures contract is a derivative.

In finance, the time value (TV) of an option is the premium a rational investor would pay over its current exercise value, based on the probability it will increase in value before expiry. For an American option this value is always greater than zero in a fair market, thus an option is always worth more than its current exercise value. As an option can be thought of as 'price insurance', TV can be thought of as the risk premium the option seller charges the buyer—the higher the expected risk, the higher the premium. Conversely, TV can be thought of as the price an investor is willing to pay for potential upside.

In finance, the intrinsic value of an asset or security is its value as calculated with regard to an inherent, objective measure. A distinction, is re the asset's price, which is determined relative to other similar assets. Note, then, that the intrinsic approach to valuation may be somewhat simplified, in that it ignores elements other than the measure in question.

In finance, a price (premium) is paid or received for purchasing or selling options. This article discusses the calculation of this premium in general. For further detail, see: Mathematical finance § Derivatives pricing: the Q world for discussion of the mathematics; Financial engineering for the implementation; as well as Financial modeling § Quantitative finance generally.

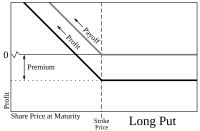

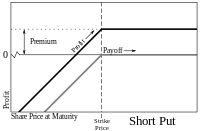

The owner of an option contract has the right to exercise it, and thus require that the financial transaction specified by the contract is to be carried out immediately between the two parties, whereupon the option contract is terminated. When exercising a call option, the owner of the option purchases the underlying shares at the strike price from the option seller, while for a put option, the owner of the option sells the underlying to the option seller, again at the strike price.

In finance, a collar is an option strategy that limits the range of possible positive or negative returns on an underlying to a specific range. A collar strategy is used as one of the ways to hedge against possible losses and it represents long put options financed with short call options. The collar combines the strategies of the protective put and the covered call.

In finance, a calendar spread is a spread trade involving the simultaneous purchase of futures or options expiring on a particular date and the sale of the same instrument expiring on another date. These individual purchases, known as the legs of the spread, vary only in expiration date; they are based on the same underlying market and strike price.

In options trading, a bull spread is a bullish, vertical spread options strategy that is designed to profit from a moderate rise in the price of the underlying security.

In options trading, a bear spread is a bearish, vertical spread options strategy that can be used when the options trader is moderately bearish on the underlying security.

A naked option or uncovered option is an options strategy where the options contract writer does not hold the underlying security position to cover the contract in case of assignment. Nor does the seller hold any option of the same class on the same underlying security that could protect against potential losses. A naked option involving a "call" is called a "naked call" or "uncovered call", while one involving a "put" is a "naked put" or "uncovered put".

In finance an iron butterfly, also known as the ironfly, is the name of an advanced, neutral-outlook, options trading strategy that involves buying and holding four different options at three different strike prices. It is a limited-risk, limited-profit trading strategy that is structured for a larger probability of earning smaller limited profit when the underlying stock is perceived to have a low volatility.

Option strategies are the simultaneous, and often mixed, buying or selling of one or more options that differ in one or more of the options' variables. Call options, simply known as Calls, give the buyer a right to buy a particular stock at that option's strike price. Opposite to that are Put options, simply known as Puts, which give the buyer the right to sell a particular stock at the option's strike price. This is often done to gain exposure to a specific type of opportunity or risk while eliminating other risks as part of a trading strategy. A very straightforward strategy might simply be the buying or selling of a single option; however, option strategies often refer to a combination of simultaneous buying and or selling of options.

The backspread is the converse strategy to the ratio spread and is also known as reverse ratio spread. Using calls, a bullish strategy known as the call backspread can be constructed and with puts, a strategy known as the put backspread can be constructed.

Pin risk occurs when the market price of the underlier of an option contract at the time of the contract's expiration is close to the option's strike price. In this situation, the underlier is said to have pinned. The risk to the writer (seller) of the option is that they cannot predict with certainty whether the option will be exercised or not. So the writer cannot hedge their position precisely and may end up with a loss or gain. There is a chance that the price of the underlier may move adversely, resulting in an unanticipated loss to the writer. In other words, an option position may result in a large, undesired risky position in the underlier immediately after expiration, regardless of the actions of the writer.

In finance, an option is a contract which conveys to its owner, the holder, the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a specific quantity of an underlying asset or instrument at a specified strike price on or before a specified date, depending on the style of the option. Options are typically acquired by purchase, as a form of compensation, or as part of a complex financial transaction. Thus, they are also a form of asset and have a valuation that may depend on a complex relationship between underlying asset price, time until expiration, market volatility, the risk-free rate of interest, and the strike price of the option. Options may be traded between private parties in over-the-counter (OTC) transactions, or they may be exchange-traded in live, public markets in the form of standardized contracts.

In finance, a credit spread, or net credit spread is an options strategy that involves a purchase of one option and a sale of another option in the same class and expiration but different strike prices. It is designed to make a profit when the spreads between the two options narrows.