Related Research Articles

Taiwanese indigenous peoples, also known as Formosans, Native Taiwanese or Austronesian Taiwanese and formerly as Taiwanese aborigines, Takasago people or Gaoshan people, are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, with the nationally recognized subgroups numbering about 569,000 or 2.38% of the island's population. This total is increased to more than 800,000 if the indigenous peoples of the plains in Taiwan are included, pending future official recognition. When including those of mixed ancestry, such a number is possibly more than a million. Academic research suggests that their ancestors have been living on Taiwan for approximately 15,000 years. A wide body of evidence suggests that the Taiwanese indigenous peoples had maintained regular trade networks with numerous regional cultures of Southeast Asia before the Han Chinese colonists began settling on the island from the 17th century, at the behest of the Dutch colonial administration and later by successive governments towards the 20th century.

Headhunting is the practice of hunting a human and collecting the severed head after killing the victim, although sometimes more portable body parts are taken instead as trophies. Headhunting was practiced in historic times in parts of Europe, East Asia, Oceania, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Mesoamerica, South America, West Africa and Central Africa.

Korean shamanism, also known as Mu-ism and musok, is a religion from Korea. Scholars of religion have classified it as a folk religion. There is no central authority in control of musok, with much diversity of belief and practice evident among practitioners.

Garifuna music is an ethnic music and dance with African, Arawak, and Kalinago elements, originating with the Afro-Indigenous Garifuna people from Central America and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. In 2001, Garifuna music, dance, and language were collectively proclaimed as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

Chinese folk religion, also known as Chinese popular religion, comprehends a range of traditional religious practices of Han Chinese, including the Chinese diaspora. Vivienne Wee described it as "an empty bowl, which can variously be filled with the contents of institutionalised religions such as Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and Chinese syncretic religions”. This includes the veneration of shen (spirits) and ancestors, exorcism of demonic forces, and a belief in the rational order of nature, balance in the universe and reality that can be influenced by human beings and their rulers, as well as spirits and deities. Worship is devoted to deities and immortals, who can be deities of places or natural phenomena, of human behaviour, or founders of family lineages. Stories of these gods are collected into the body of Chinese mythology. By the Song dynasty (960–1279), these practices had been blended with Buddhist, Confucianist doctrines and Taoist teachings to form the popular religious system which has lasted in many ways until the present day. The present day government of mainland China, like the imperial dynasties, tolerates popular religious organizations if they bolster social stability but suppresses or persecutes those that they fear would undermine it.

The Paiwan are an indigenous people of Taiwan. They speak the Paiwan language. In 2014, the Paiwan numbered 96,334. This was approximately 17.8% of Taiwan's total indigenous population, making them the second-largest indigenous group.

The Atayal, also known as the Tayal and the Tayan, are a Taiwanese indigenous people. The Atayal people number around 90,000, approximately 15.9% of Taiwan's total indigenous population, making them the third-largest indigenous group. The preferred endonym is "Tayal", although the Taiwanese government officially recognizes them as "Atayal".

The Bunun, also historically known as the Vonum, are a Taiwanese indigenous people. They speak the Bunun language. Unlike other aboriginal peoples in Taiwan, the Bunun are widely dispersed across the island's central mountain ranges. In the year 2000, the Bunun numbered 41,038. This was approximately 8% of Taiwan's total indigenous population, making them the fourth-largest indigenous group. They have five distinct communities: the Takbunuaz, the Takituduh, the Takibaka, the Takivatan, and the Isbukun.

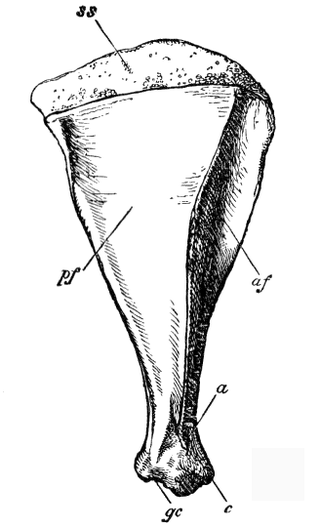

Scapulimancy is the practice of divination by use of scapulae or speal bones. It is most widely practiced in China and the Sinosphere as oracle bones, but has also been independently developed in other traditions including the West.

The Hmong people are an ethnic group currently native to several countries, believed to have come from the Yangtze river basin area in southern China. The Hmong are known in China as the Miao, which encompasses not only Hmong, but also other related groups such as Hmu, Qo Xiong and A-Hmao. There is debate about usage of this term, especially amongst Hmong living in the West, as it is believed by some to be derogatory, although Hmong living in China still call themselves by this name. Throughout recorded history, the Hmong have remained identifiable as Hmong because they have maintained the Hmong language, customs, and ways of life while adopting the ways of the country in which they live. In the 1960s and 1970s, many Hmong were secretly recruited by the American CIA to fight against communism during the Vietnam War. After American armed forces pulled out of Vietnam the Pathet Lao, a communist regime, took over in Laos and ordered the prosecution and re-education of all those who had fought against its cause during the war. While many Hmong are still left in Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, and China, since 1975 many Hmong have fled Laos in fear of persecution. Housed in Thai refugee camps during the 1980s, many have resettled in countries such as the United States, French Guiana, Australia, France, Germany, as well as some who have chosen to stay in Thailand in hope of returning to their own land. In the United States, new generations of Hmong are gradually assimilating into American society while being taught Hmong culture and history by their elders. Many fear that as the older generations pass on, the knowledge of the Hmong among Hmong Americans will die as well.

The Puyuma language or Pinuyumayan, is the language of the Puyuma, an indigenous people of Taiwan. It is a divergent Formosan language of the Austronesian family. Most speakers are older adults.

The Sakizaya are Taiwanese indigenous peoples with a population of approximately 1,000. They primarily live in Hualien, where their culture is centered.

Yatiri are medical practitioners and community healers among the Aymara of Bolivia, Chile and Peru, who use in their practice both symbols and materials such as coca leaves. Yatiri are a special subclass of the more generic category Qulliri, a term used for any traditional healer in Aymara society.

The Papuans are one of four major cultural groups of Papua New Guinea. The majority of the population lives in rural areas. In isolated areas there remains a handful of the giant communal structures that previously housed the whole male population, with a circling cluster of huts for the women. The Papuan people are Melanesian people composed of at least 240 different peoples, each with its own language and culture. Sago is the staple food of the Papuan supplemented with hunting, fishing and small gardens.

The Nahua of La Huasteca is an indigenous ethnic group of Mexico and one of the Nahua peoples. They live in the mountainous area called La Huasteca which is located in north eastern Mexico and contains parts of the states of Hidalgo, Veracruz and Puebla. They speak one of the Huasteca Nahuatl dialects: western, central or eastern Huasteca Nahuatl.

The Jivaroan peoples are the indigenous peoples in the headwaters of the Marañon River and its tributaries, in northern Peru and eastern Ecuador. The tribes speak the Chicham languages.

The Ryukyuan religion (琉球信仰), Ryūkyū Shintō (琉球神道), Nirai Kanai Shinkō (ニライカナイ信仰), or Utaki Shinkō (御嶽信仰) is the indigenous belief system of the Ryukyu Islands.

Shamanism was the dominant religion of the Jurchen people of northeast Asia and of their descendants, the Manchu people. As early as the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), the Jurchens conducted shamanic ceremonies at shrines called tangse. There were two kinds of shamans: those who entered in a trance and let themselves be possessed by the spirits, and those who conducted regular sacrifices to heaven, to a clan's ancestors, or to the clan's protective spirits.

Shamanism is a religious practice present in various cultures and religions around the world. Shamanism takes on many different forms, which vary greatly by region and culture and are shaped by the distinct histories of its practitioners.

The mengdu, also called the three mengdu and the three mengdu of the sun and moon, are a set of three kinds of brass ritual devices—a pair of knives, a bell, and divination implements—which are the symbols of shamanic priesthood in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. Although similar ritual devices are found in mainland Korea, the religious reverence accorded to the mengdu is unique to Jeju.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cauquelin, J. (2004) The Aborigines of Taiwan; The Puyuma: from headhunting to the modern world. RoutledgeCurzon, London.

- ↑ http://140.133.6.46/ETD-db/ETD-search/view_etd?URN=etd-0723110-171901%5B%5D

- ↑ http://www.ipcf.org.tw/ipcf/associate/tribe/tribeDetail.htmlCID=1FE45C38A00FAC61&sn=AEB8BBC40B9D7837143331A7531EBAF5%5B%5D

- 1 2 3 "原住民族文化傳播網 ::". Archived from the original on 2013-06-16. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- 1 2 Cauquelin, J. (2004) The Aborigines of Taiwan; The Puyuma: from headhunting to the modern world. RoutledgeCurzon, London

- ↑ Cauquelin, J. (2008) Ritual Texts of the Last Traditional Practitioners of Nanwang Puyuma. Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, Taipei.

- ↑ Cauquelin, J. (2004) The Aborigines of Taiwan; The Puyuma: from headhunting to the modern world. RoutledgeCurzon, London