Macroeconomics is a branch of economics that deals with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole. This includes regional, national, and global economies. Macroeconomists study topics such as output/GDP and national income, unemployment, price indices and inflation, consumption, saving, investment, energy, international trade, and international finance.

In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high or increasing, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since actions intended to lower inflation may exacerbate unemployment.

Unemployment, according to the OECD, is people above a specified age not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the reference period.

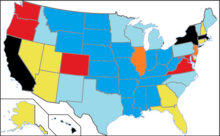

The United States is a highly developed/advanced mixed economy. It is the world's largest economy by nominal GDP, and the second-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP) behind China. It has the world's seventh-highest per capita GDP (nominal) and the eighth-highest per capita GDP (PPP) as of 2022. The U.S. accounted for 25.4% of the global economy in 2022 in nominal terms, and around 15.6% in PPP terms. The U.S. dollar is the currency of record most used in international transactions and is the world's reserve currency, backed by a large U.S. treasuries market, its role as the reference standard for the petrodollar system, and its linked eurodollar. Several countries use it as their official currency and in others it is the de facto currency.

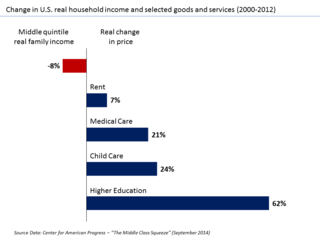

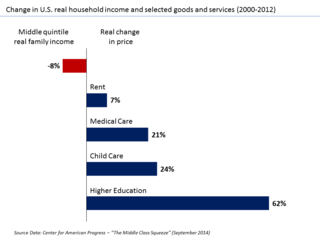

In economics, inflation is a general increase in the prices of goods and services in an economy. This is usually measured using the consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduction in the purchasing power of money. The opposite of CPI inflation is deflation, a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. The common measure of inflation is the inflation rate, the annualized percentage change in a general price index. As prices faced by households do not all increase at the same rate, the consumer price index (CPI) is often used for this purpose.

Full employment is a situation in which there is no cyclical or deficient-demand unemployment. Full employment does not entail the disappearance of all unemployment, as other kinds of unemployment, namely structural and frictional, may remain. For instance, workers who are "between jobs" for short periods of time as they search for better employment are not counted against full employment, as such unemployment is frictional rather than cyclical. An economy with full employment might also have unemployment or underemployment where part-time workers cannot find jobs appropriate to their skill level, as such unemployment is considered structural rather than cyclical. Full employment marks the point past which expansionary fiscal and/or monetary policy cannot reduce unemployment any further without causing inflation.

New Keynesian economics is a school of macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroeconomics.

The Phillips curve is an economic model, named after Bill Phillips, that correlates reduced unemployment with increasing wages in an economy. While Phillips did not directly link employment and inflation, this was a trivial deduction from his statistical findings. Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow made the connection explicit and subsequently Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps put the theoretical structure in place.

Underemployment is the underuse of a worker because their job does not use their skills, offers them too few hours, or leaves the worker idle. It contrasts from unemployment, where a person lacks a job at all despite wanting one.

The economies of Canada and the United States are similar because both are developed countries. While both countries feature in the top ten economies in the world in 2022, the U.S. is the largest economy in the world, with US$24.8 trillion, with Canada ranking ninth at US$2.2 trillion.

In economics, nominal value refers to value measured in terms of absolute money amounts, whereas real value is considered and measured against the actual goods or services for which it can be exchanged at a given time. For example, if one is offered a salary of $40,000, in that year, the real and nominal values are both $40,000. The following year, any inflation means that although the nominal value remains $40,000, because prices have risen, the salary will buy fewer goods and services, and thus its real value has decreased in accordance with inflation. On the other hand, an asset that holds its value, such as a diamond, may increase in nominal price from year to year, but its real value, i.e. its value in relation to other goods and services for which it can be exchanged, or its purchasing power, is consistent over time, because inflation has affected both its nominal value and other goods' nominal values. In spite of changes in the price, it can be sold and an equivalent amount of other gemstones such as emeralds can be purchased, because the emeralds' prices will have increased with inflation as well.

In economics, the Baumol effect, also known as Baumol's cost disease, is the rise of wages in jobs that have experienced little or no increase in labor productivity in response to rising wages in other jobs that have experienced higher productivity growth. The phenomenon was described by William J. Baumol and William G. Bowen in the 1960s and is an example of cross elasticity of demand.

Economic stagnation is a prolonged period of slow economic growth, usually accompanied by high unemployment. Under some definitions, slow means significantly slower than potential growth as estimated by macroeconomists, even though the growth rate may be nominally higher than in other countries not experiencing economic stagnation.

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Keynes in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). It was formulated most notably by John Hicks (1937), Franco Modigliani (1944), and Paul Samuelson (1948), who dominated economics in the post-war period and formed the mainstream of macroeconomic thought in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

The middle-class squeeze refers to negative trends in the standard of living and other conditions of the middle class of the population. Increases in wages fail to keep up with inflation for middle-income earners, leading to a relative decline in real wages, while at the same time, the phenomenon fails to have a similar effect on the top wage earners. People belonging to the middle class find that inflation in consumer goods and the housing market prevent them from maintaining a middle-class lifestyle, undermining aspirations of upward mobility.

Non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is a theoretical level of unemployment below which inflation would be expected to rise. It was first introduced as NIRU by Franco Modigliani and Lucas Papademos in 1975, as an improvement over the "natural rate of unemployment" concept, which was proposed earlier by Milton Friedman.

Macroeconomic theory has its origins in the study of business cycles and monetary theory. In general, early theorists believed monetary factors could not affect real factors such as real output. John Maynard Keynes attacked some of these "classical" theories and produced a general theory that described the whole economy in terms of aggregates rather than individual, microeconomic parts. Attempting to explain unemployment and recessions, he noticed the tendency for people and businesses to hoard cash and avoid investment during a recession. He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.

The Fei–Ranis model of economic growth is a dualism model in developmental economics or welfare economics that has been developed by John C. H. Fei and Gustav Ranis and can be understood as an extension of the Lewis model. It is also known as the Surplus Labor model. It recognizes the presence of a dual economy comprising both the modern and the primitive sector and takes the economic situation of unemployment and underemployment of resources into account, unlike many other growth models that consider underdeveloped countries to be homogenous in nature. According to this theory, the primitive sector consists of the existing agricultural sector in the economy, and the modern sector is the rapidly emerging but small industrial sector. Both the sectors co-exist in the economy, wherein lies the crux of the development problem. Development can be brought about only by a complete shift in the focal point of progress from the agricultural to the industrial economy, such that there is augmentation of industrial output. This is done by transfer of labor from the agricultural sector to the industrial one, showing that underdeveloped countries do not suffer from constraints of labor supply. At the same time, growth in the agricultural sector must not be negligible and its output should be sufficient to support the whole economy with food and raw materials. Like in the Harrod–Domar model, saving and investment become the driving forces when it comes to economic development of underdeveloped countries.

Wage growth is a rise of wage adjusted for inflations, often expressed in percentage. In macroeconomics, wage growth is one of the main indications to measure economic growth for a long-term since it reflects the consumer's purchasing power in the economy as well as the level of living standards. An increase in wage growth implies price inflation in the economy while a low wage growth indicates deflation that needs artificial interferences such as through fiscal policies by federal/state government. Minimum wage law is often introduced to increase wage growth by stimulating price inflations from corresponding purchasing powers in the economy. Wage growth can also be maximised through the development of industry factors by investing skilled workers in which decision made by businesses. More financial compensation for skilled workers not only lifts wage growth but stimulates higher market prices in the economy.

The decoupling of wages from productivity, sometimes known as the great decoupling, is the gap between the growth rate of median wages and the growth rate of GDP. Economists began to acknowledge this problem toward the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century. This problem furthermore leads to wage stagnation despite continued economic growth.