A threshing machine or a thresher is a piece of farm equipment that separates grain seed from the stalks and husks. It does so by beating the plant to make the seeds fall out. Before such machines were developed, threshing was done by hand with flails: such hand threshing was very laborious and time-consuming, taking about one-quarter of agricultural labour by the 18th century. Mechanization of this process removed a substantial amount of drudgery from farm labour. The first threshing machine was invented circa 1786 by the Scottish engineer Andrew Meikle, and the subsequent adoption of such machines was one of the earlier examples of the mechanization of agriculture. During the 19th century, threshers and mechanical reapers and reaper-binders gradually became widespread and made grain production much less laborious.

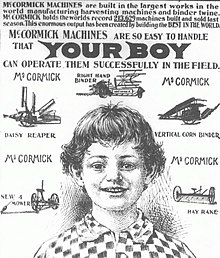

Cyrus Hall McCormick was an American inventor and businessman who founded the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, which later became part of the International Harvester Company in 1902. Originally from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, he and many members of the McCormick family became prominent residents of Chicago. McCormick has been simplistically credited as the single inventor of the mechanical reaper.

A scythe is an agricultural hand tool for mowing grass or harvesting crops. It is historically used to cut down or reap edible grains, before the process of threshing. The scythe has been largely replaced by horse-drawn and then tractor machinery, but is still used in some areas of Europe and Asia. Reapers are bladed machines that automate the cutting of the scythe, and sometimes subsequent steps in preparing the grain or the straw or hay.

The modern combine harvester, or simply combine, is a machine designed to harvest a variety of grain crops. The name derives from its combining four separate harvesting operations—reaping, threshing, gathering, and winnowing—to a single process. Among the crops harvested with a combine are wheat, rice, oats, rye, barley, corn (maize), sorghum, millet, soybeans, flax (linseed), sunflowers and rapeseed. The separated straw, left lying on the field, comprises the stems and any remaining leaves of the crop with limited nutrients left in it: the straw is then either chopped, spread on the field and ploughed back in or baled for bedding and limited-feed for livestock.

A mower is a person or machine that cuts (mows) grass or other plants that grow on the ground. Usually mowing is distinguished from reaping, which uses similar implements, but is the traditional term for harvesting grain crops, e.g. with reapers and combines.

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting or reaping grain crops, or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock. Falx was a synonym but was later used to mean any of a number of tools that had a curved blade that was sharp on the inside edge such as a scythe.

The reaper-binder, or binder, is a farm implement that improved upon the simple reaper. The binder was invented in 1872 by Charles Baxter Withington, a jeweler from Janesville, Wisconsin. In addition to cutting the small-grain crop, a binder also 'binds' the stems into bundles or sheaves. These sheaves are usually then 'shocked' into A-shaped conical stooks, resembling small tipis, to allow the grain to dry for several days before being picked up and threshed.

A swather, or windrower, is a farm implement that cuts hay or small grain crops and forms them into a windrow for drying.

A stook /stʊk/, also referred to as a shock or stack, is an arrangement of sheaves of cut grain-stalks placed so as to keep the grain-heads off the ground while still in the field and before collection for threshing. Stooked grain sheaves are typically wheat, barley and oats. In the era before combine harvesters and powered grain driers, stooking was necessary to dry the grain for a period of days to weeks before threshing, to achieve a moisture level low enough for storage. In the 21st century, most grain is produced with the mechanized and powered methods, and is therefore not stooked at all. However, stooking remains useful to smallholders who grow their own grain, or at least some of it, as opposed to buying it.

Robert Hall McCormick was an American inventor who invented numerous devices including a version of the reaper which his eldest son Cyrus McCormick patented in 1834 and became the foundation of the International Harvester Company. Although he lived his life in rural Virginia, he was patriarch of the McCormick family that became influential throughout the world, especially in large cities such as Chicago, Washington, D.C., and New York City.

The Cyrus McCormick Farm and Workshop is on the family farm of inventor Cyrus Hall McCormick known as Walnut Grove. Cyrus Hall McCormick improved and patented the mechanical reaper, which eventually led to the creation of the combine harvester.

Obed Hussey (1792–1860) was an American inventor. His most notable invention was a reaping machine, patented in 1833, that was a rival of a similar machine, patented in 1834, produced by Cyrus McCormick. Hussey also invented a steam plow, a machine for grinding out hooks and eyes, a mill for grinding corn and cobs, a husking machine, a machine for crushing sugar cane, a machine for making artificial ice, a candle-making machine, and other devices. However, he devoted the prime of his life to perfecting his reaping machine.

A grain cradle or cradle, is a modification to a standard scythe to keep the cut grain stems aligned. The cradle scythe has an additional arrangement of fingers attached to the snaith to catch the cut grain so that it can be cleanly laid down in a row with the grain heads aligned for collection and efficient threshing.

Patrick Bell was a Church of Scotland minister and inventor.

Agricultural machinery relates to the mechanical structures and devices used in farming or other agriculture. There are many types of such equipment, from hand tools and power tools to tractors and the countless kinds of farm implements that they tow or operate. Diverse arrays of equipment are used in both organic and nonorganic farming. Especially since the advent of mechanised agriculture, agricultural machinery is an indispensable part of how the world is fed. Agricultural machinery can be regarded as part of wider agricultural automation technologies, which includes the more advanced digital equipment and robotics. While agricultural robots have the potential to automate the three key steps involved in any agricultural operation, conventional motorized machinery is used principally to automate only the performing step where diagnosis and decision-making are conducted by humans based on observations and experience.

John Henry Manny (1825–1856) was the inventor of the Manny Reaper, one of various makes of reaper used to harvest grain in the 19th century. Cyrus McCormick III, in his Century of the Reaper, called Manny "the most brilliant and successful of all Cyrus McCormick's competitors," a field of many brilliant people.

The McCormick–International Harvester Company Branch House was built in 1898 in Madison, Wisconsin as a distribution center for farm implements of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company. After McCormick merged into the International Harvester Company in 1902, the building was expanded and served the same function for the new company. In 2010 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

A sheaf is a bunch of cereal-crop stems bound together after reaping, traditionally by sickle, later by scythe or, after its introduction in 1872, by a mechanical reaper-binder.

Stripper was a type of harvesting machine common in Australia in the late 19th and early 20th century. John Ridley is now accepted as its inventor, though John Wrathall Bull argued strongly for the credit.