Related Research Articles

The Poetic Edda is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems, which is distinct from the Prose Edda written by Snorri Sturluson. Several versions exist, all primarily of text from the Icelandic medieval manuscript known as the Codex Regius, which contains 31 poems. The Codex Regius is arguably the most important extant source on Norse mythology and Germanic heroic legends. Since the early 19th century, it has had a powerful influence on Scandinavian literature, not only through its stories, but also through the visionary force and the dramatic quality of many of the poems. It has also been an inspiration for later innovations in poetic meter, particularly in Nordic languages, with its use of terse, stress-based metrical schemes that lack final rhymes, instead focusing on alliterative devices and strongly concentrated imagery. Poets who have acknowledged their debt to the Codex Regius include Vilhelm Ekelund, August Strindberg, J. R. R. Tolkien, Ezra Pound, Jorge Luis Borges, and Karin Boye.

In Norse mythology, a valkyrie is one of a host of female figures who guide souls of the dead to the god Odin's hall Valhalla. There, the deceased warriors become einherjar. When the einherjar are not preparing for the events of Ragnarök, the valkyries bear them mead. Valkyries also appear as lovers of heroes and other mortals, where they are sometimes described as the daughters of royalty, sometimes accompanied by ravens and sometimes connected to swans or horses.

Sigrún is a valkyrie in Norse mythology. Her story is related in Helgakviða Hundingsbana I and Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, in the Poetic Edda. The original editor annotated that she was Sváfa reborn.

In Norse mythology, a dís is a female deity, ghost, or spirit associated with Fate who can be either benevolent or antagonistic toward mortals. Dísir may act as protective spirits of Norse clans. It is possible that their original function was that of fertility goddesses who were the object of both private and official worship called dísablót, and their veneration may derive from the worship of the spirits of the dead. The dísir, like the valkyries, norns, and vættir, are always referred collectively in surviving references. The North Germanic dísir and West Germanic Idisi are believed by some scholars to be related due to linguistic and mythological similarities, but the direct evidence of Anglo-Saxon and Continental German mythology is limited. The dísir play roles in Norse texts that resemble those of fylgjur, valkyries, and norns, so that some have suggested that dísir is a broad term including the other beings.

Old Norse religion, also known as Norse paganism, is the most common name for a branch of Germanic religion which developed during the Proto-Norse period, when the North Germanic peoples separated into a distinct branch of the Germanic peoples. It was replaced by Christianity and forgotten during the Christianisation of Scandinavia. Scholars reconstruct aspects of North Germanic Religion by historical linguistics, archaeology, toponymy, and records left by North Germanic peoples, such as runic inscriptions in the Younger Futhark, a distinctly North Germanic extension of the runic alphabet. Numerous Old Norse works dated to the 13th-century record Norse mythology, a component of North Germanic religion.

The Wulfings, Wylfings or Ylfings was a powerful clan in Beowulf, Widsith and in the Norse sagas. While the poet of Beowulf does not locate the Wulfings geographically, Scandinavian sources define the Ylfings as the ruling clan of the Eastern Geats.

Helgi Hundingsbane is a hero in Norse sagas. Helgi appears in Volsunga saga and in two lays in the Poetic Edda named Helgakviða Hundingsbana I and Helgakviða Hundingsbana II. The Poetic Edda relates that Helgi and his mistress Sigrún were Helgi Hjörvarðsson and Sváva of the Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar reborn. They were once again reborn as Helgi Haddingjaskati and Kára whose story survives as a part of the Hrómundar saga Gripssonar.

"Völsungakviða" or "Helgakviða Hundingsbana I" is an Old Norse poem found in the Poetic Edda. It constitutes one of the Helgi lays, together with Helgakviða Hundingsbana II and Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar.

"Völsungakviða in forna" or "Helgakviða Hundingsbana II" is an Old Norse poem found in the Poetic Edda. It constitutes one of the Helgi lays together with Helgakviða Hundingsbana I and Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar.

Narfi, also Nörfi, Nari or Nörr, is a jötunn in Norse mythology, and the father of Nótt, the personified night.

Olaf Gudrødsson, known after his death as Olaf Geirstad-Alf "Olaf, Elf of Geirstad", was a semi-legendary petty king in Norway. A member of the House of Yngling, he was the son of Gudrød the Hunter and according to the late Heimskringla, a half-brother of Halfdan the Black. Gudrød and Olaf ruled a large part of Raumarike. The Þáttr Ólafs Geirstaða Alfs in Flateyjarbók records a fantastical story of how he was worshipped after his death and on his own instructions, his body was then decapitated so that he could be reborn as Olaf II of Norway (St. Olaf).

Hrómundar saga Gripssonar or The Saga of Hromund Gripsson is a legendary saga from Iceland. The original version has been lost, but its content has been preserved in the rímur of Hrómundr Gripsson, known as Griplur, which were probably composed in the first half of the 14th century, but appeared in print in 1896 in Fernir forníslenzkar rímnaflokkar, edited by Finnur Jónsson. These rímur were the basis for the not very appreciated Hrómunds saga which is found in the 17th-century MS of the Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collection, AM 587b 4°, as well as thirty-eight known later manuscripts. The saga as we now have it contains a number of narrative discrepancies, which are probably the result of the scribe working from a partly illegible manuscript of the rímur.

In Tacitus' work Germania from the year 98, regnator omnium deus was a deity worshipped by the Semnones tribe in a sacred grove. Comparisons have been made between this reference and the poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II, recorded in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources.

In Norse mythology, Kára is a valkyrie, attested in the prose epilogue of the Poetic Edda poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II.

Helgi Haddingjaskati was a legendary Norse hero of whom only fragmentary accounts survive.

The Haddingjar refers on the one hand to Germanic heroic legends about two brothers by this name, and on the other hand to possibly related legends based on the Hasdingi, the royal dynasty of the Vandals. The accounts vary greatly.

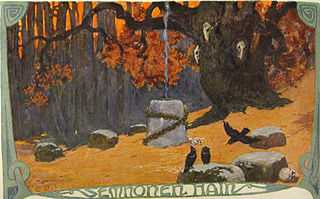

A grove of Fetters is mentioned in the Eddic poem "Helgakviða Hundingsbana II":

Heitstrenging (pl. heitstrengingar) is an Old Norse term referring to the swearing of a solemn oath to perform a future action. They were often performed at Yule and other large social events, where they played a role in establishing and maintaining good relationships principally between members of the aristocratic warrior elite. The oath-swearing practice varied significantly, sometimes involving ritualised drinking or placing hands on a holy pig that could later be sacrificed. While originally containing heathen religious components such as prayers and worship of gods such as Freyr and Thor, the practice continued in an altered manner after the Christianisation of Scandinavia.

Death in Norse paganism was associated with diverse customs and beliefs that varied with time, location and social group, and did not form a structured, uniform system. After the funeral, the individual could to a range of afterlives including Valhalla, Hel and living on physically in the landscape. These afterlives show blurred boundaries and exist alongside a number of minor afterlives that may have been significant in Nordic paganism. The dead were also seen as being able to bestow land fertility, often in return for votive offerings, and knowledge, either willingly or after coercion. Many of these beliefs and practices continued in altered forms after the Christianisation of the Germanic peoples in folk belief.

The sonargǫltr or sónargǫltr was the boar sacrificed as part of the celebration of Yule in Germanic paganism, on whose bristles solemn vows were made in some forms of a tradition known as heitstrenging.

References

- ↑ Cited in de Vries, p. 217.

- ↑ Hilda Roderick Ellis, The Road to Hel: A Study of the Conception of the Dead in Old Norse Literature, Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1943, repr. New York: Greenwood, 1968, OCLC 311911348, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 Jan de Vries, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte , Grundriß der germanischen Philologie 12.1, Berlin: De Gruyter, 1935, rev. ed. 1956, repr. as 3rd ed. 1970, OCLC 848545556, p. 183 (in German).

- ↑ "Haddingjar" in: John Lindow, Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, 2001, repr. Oxford: Oxford University, 2002, ISBN 9780195153828, p. 157.

- 1 2 3 N. K. Chadwick, "Norse Ghosts (A Study in the Draugr and the Haugbúi", Folklore 57.2, June 1946, pp. 50–65, pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Ellis, p. 140.

- ↑ Ellis, pp. 138–39.

- ↑ E. O. G. Turville-Petre, Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia, History of Religion, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964, OCLC 606010675, pp. 193–95: "We can safely say that some people thought that St Ólaf was his older namesake reborn".

- ↑ Chadwick, p. 58 and note 18.

- ↑ Ellis, pp. 140–41.

- ↑ Ellis, pp. 139–42.

- ↑ Gustav Storm, "Vore Forfædres Tro paa Sjælvandring og deres Opkaldelsessystem", Arkiv för nordisk filologi (1893) 119–20; cited in Ellis, pp. 143–44.

- 1 2 Max Keil, Altisländische Namenwahl, Palaestra 176, Leipzig: Mayer & Müller, 1931, OCLC 898959310; cited in Ellis, pp. 142, 144–45.

- ↑ De Vries, p. 218.

- ↑ Ellis, p. 146.

- ↑ Thomas A. DuBois, Nordic Religions in the Viking Age, The Middle Ages Series, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1999, ISBN 9780812217148, p. 75.

- ↑ Karl August Eckhardt, Irdische Unsterblichkeit: germanischer Glaube an die Wiederverkörperung in der Sippe, Studien zur Rechts- und Religionsgeschichte 1, Weimar: Böhlau, 1937, OCLC 977866293, p. 128, cited in de Vries, Volume 1, p. 79, note 2.