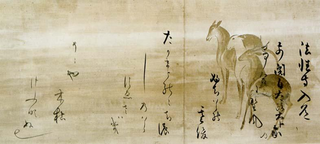

The Heian period is the last division of classical Japanese history, running from 794 to 1185. It followed the Nara period, beginning when the 50th emperor, Emperor Kammu, moved the capital of Japan to Heian-kyō. Heian (平安) means "peace" in Japanese. It is a period in Japanese history when the Chinese influences were in decline and the national culture matured. The Heian period is also considered the peak of the Japanese imperial court and noted for its art, especially poetry and literature. Two types of Japanese script emerged, including katakana, a phonetic script which was abbreviated into hiragana, a cursive alphabet with a unique writing method distinctive to Japan. This gave rise to Japan's famous vernacular literature, with many of its texts written by court women who were not as educated in Chinese compared to their male counterparts.

Japanese literature throughout most of its history has been influenced by cultural contact with neighboring Asian literatures, most notably China and its literature. Early texts were often written in pure Classical Chinese or lit. 'Chinese writing', a Chinese-Japanese creole language. Indian literature also had an influence through the spread of Buddhism in Japan.

Kamo no Chōmei was a Japanese author, poet, and essayist. He witnessed a series of natural and social disasters, and, having lost his political backing, was passed over for promotion within the Shinto shrine associated with his family. He decided to turn his back on society, took Buddhist vows, and became a hermit, living outside the capital. This was somewhat unusual for the time, when those who turned their backs on the world usually joined monasteries. Along with the poet-priest Saigyō he is representative of the literary recluses of his time, and his celebrated essay Hōjōki is representative of the genre known as "recluse literature".

The Pillow Book is a book of observations and musings recorded by Sei Shōnagon during her time as court lady to Empress Consort Teishi during the 990s and early 1000s in Heian-period Japan. The book was completed in the year 1002.

Urabe Kenkō, also known as Yoshida Kenkō, or simply Kenkō (兼好), was a Japanese author and Buddhist monk. His most famous work is Tsurezuregusa, one of the most studied works of medieval Japanese literature. Kenko wrote during the Muromachi and Kamakura periods.

Japanese philosophy has historically been a fusion of both indigenous Shinto and continental religions, such as Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. Formerly heavily influenced by both Chinese philosophy and Indian philosophy, as with Mitogaku and Zen, much modern Japanese philosophy is now also influenced by Western philosophy.

Onmyōdō is a system of natural science, astronomy, almanac, divination and magic that developed independently in Japan based on the Chinese philosophies of yin and yang and wuxing. The philosophy of yin and yang and wu xing was introduced to Japan at the beginning of the 6th century, and, influenced by Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, evolved into the earliest system of Onmyōdō around the late 7th century. In 701, the Taiho Code established the departments and posts of onmyōji who practiced Onmyōdō in the Imperial Court, and Onmyōdō was institutionalized. From around the 9th century during the Heian period, Onmyōdō interacted with Shinto and Goryō worship (御霊信仰) in Japan, and developed into a system unique to Japan. Abe no Seimei, who was active during Heian period, is the most famous onmyōji in Japanese history and has appeared in various Japanese literature in later years. Onmyōdō was under the control of the imperial government, and later its courtiers, the Tsuchimikado family, until the middle of the 19th century, at which point it became prohibited as superstition.

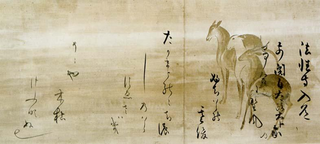

Tsurezuregusa is a collection of essays written by the Japanese monk Kenkō (兼好) between 1330 and 1332. The work is widely considered a gem of medieval Japanese literature and one of the three representative works of the zuihitsu genre, along with The Pillow Book and the Hōjōki.

The Twenty-Two Shrines of Japan is one ranking system for Shinto shrines. The system was established during the Heian period and formed part of the government's systematization of Shinto during the emergence of a general anti-Chinese sentiment and the suppression of the Taoist religion. It involved the establishment of the shrines as important centers of public life in Japan. It played a role in official imperial ceremonies such as the Practice of Chinkon. An extensive body of literature also emerged containing information about each shrine, including the shrine's origin, priestly dress, divine treatises, the system of shrine removal, subordinate shrines, and annual cycle of rituals, among others.

Hōjōki, variously translated as An Account of My Hut or The Ten Foot Square Hut, is an important and popular short work of the early Kamakura period (1185–1333) in Japan by Kamo no Chōmei. Written in March 1212, the work depicts the Buddhist concept of impermanence (mujō) through the description of various disasters such as earthquake, famine, whirlwind and conflagration that befall the people of the capital city Kyoto. The author Chōmei, who in his early career worked as court poet and was also an accomplished player of the biwa and koto, became a Buddhist monk in his fifties and moved farther and farther into the mountains, eventually living in a 10-foot square hut located at Mt. Hino. The work has been classified both as belonging to the zuihitsu genre and as Buddhist literature. Now considered as a Japanese literary classic, the work remains part of the Japanese school curriculum.

Penguin Great Ideas is a series of largely non-fiction books published by Penguin Books. Titles contained within this series are considered to be world-changing, influential and inspirational. Topics covered include philosophy, politics, science and war. The texts for the series have been extracted from previously published Penguin Classics and Penguin Modern Classics titles and purged of all editorial apparatus, making them appear as standalone texts. The concept of repurposed extracts was inspired by an earlier Penguin series produced in the mid-1990s, the Penguin's 60 Classics, which were extracts of classic texts published in a small book format at the time of Penguin's 60th anniversary. The typographic cover designs of the series have been highly praised, winning prizes such as a D&AD award in 2005.

Zuihitsu (随筆) is a genre of Japanese literature consisting of loosely connected personal essays and fragmented ideas that typically respond to the author's surroundings. The name is derived from two Kanji meaning "at will" and "pen." The provenance of the term is ultimately Chinese, zuihitsu being the Sino-Japanese reading (on'yomi) of 随筆, the native reading (kun'yomi) of which is fude ni shitagau. Thus works of the genre should be considered not as traditionally planned literary pieces but rather as casual or randomly recorded thoughts by the authors.

Buddhist poetry is a genre of literature that forms a part of Buddhist discourse.

Hosshō-ji was a Buddhist temple in northeastern Kyoto, Japan, endowed by Emperor Shirakawa in fulfillment of a sacred vow. The temple complex was located east of the Kamo River in the Shirakawa district; and its chief architectural feature was a nine-storied octagonal pagoda.

Chiteiki is a classic work of Japanese non-fiction literature written during the late tenth century by Yoshishige no Yasutane 慶滋保胤. Composed in Sino-Japanese, Chiteiki is considered a foundational example of recluse writing known as “thatched-hut literature”. The style belongs to a genre called zuihitsu 随筆, which might be compared to the writing style of a diary or modern blog for its loosely connected, “train of thought” character.

Heian literature or Chūko literature refers to Japanese literature of the Heian period, running from 794 to 1185. This article summarizes its history and development.

Japan's medieval period was a transitional period for the nation's literature. Kyoto ceased being the sole literary centre as important writers and readerships appeared throughout the country, and a wider variety of genres and literary forms developed accordingly, such as the gunki monogatari and otogi-zōshi prose narratives, and renga linked verse, as well as various theatrical forms such as noh. Medieval Japanese literature can be broadly divided into two periods: the early and late middle ages, the former lasting roughly 150 years from the late 12th to the mid-14th century, and the latter until the end of the 16th century.